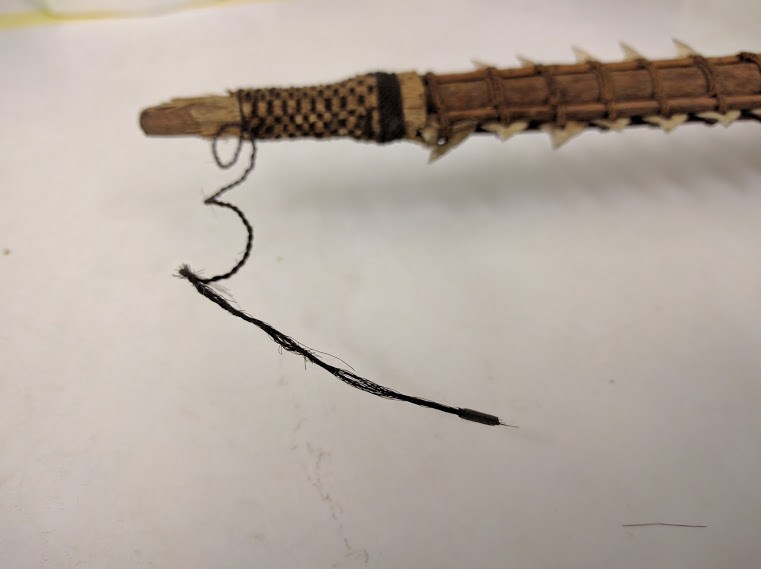

In museums, we are used to coming across many wonderful objects made from a variety of fantastic materials. But is everything really what it appears? When presented with a Kiribati shark-toothed sword, from the Museum of Archaeology & Anthropology, decorated with braids of human hair, I started to think of ways I could interrogate these materials and find out what they really were.

In museums, we are used to coming across many wonderful objects made from a variety of fantastic materials. But is everything really what it appears? When presented with a Kiribati shark-toothed sword, decorated with braids of human hair, I started to think of ways I could interrogate these materials and find out what they really were.

It was obvious from a visual inspection that the shark teeth were real. But what type of shark did these teeth come from? Was this species available to the people of Kiribati in the late 1800s, when the sword was made? To answer these questions, I enlisted the help of Dr. Kelly Richards of the Zoology Department here at the University of Cambridge. Working from photographs, she was able to use the size, shape and serrations of the teeth to tell me that there were in fact two species of shark present on this sword! One was probably a silvertip shark or a silky shark, while the other was likely an oceanic whitetip shark or a pigeye shark. All of these sharks were present in the waters around Kiribati at the time, but having multiple species on one sword is contrary to academic consensus about the manufacturing methods of shark tooth weapons on Kiribati. This discovery led to a new set of questions that I hadn’t considered before!

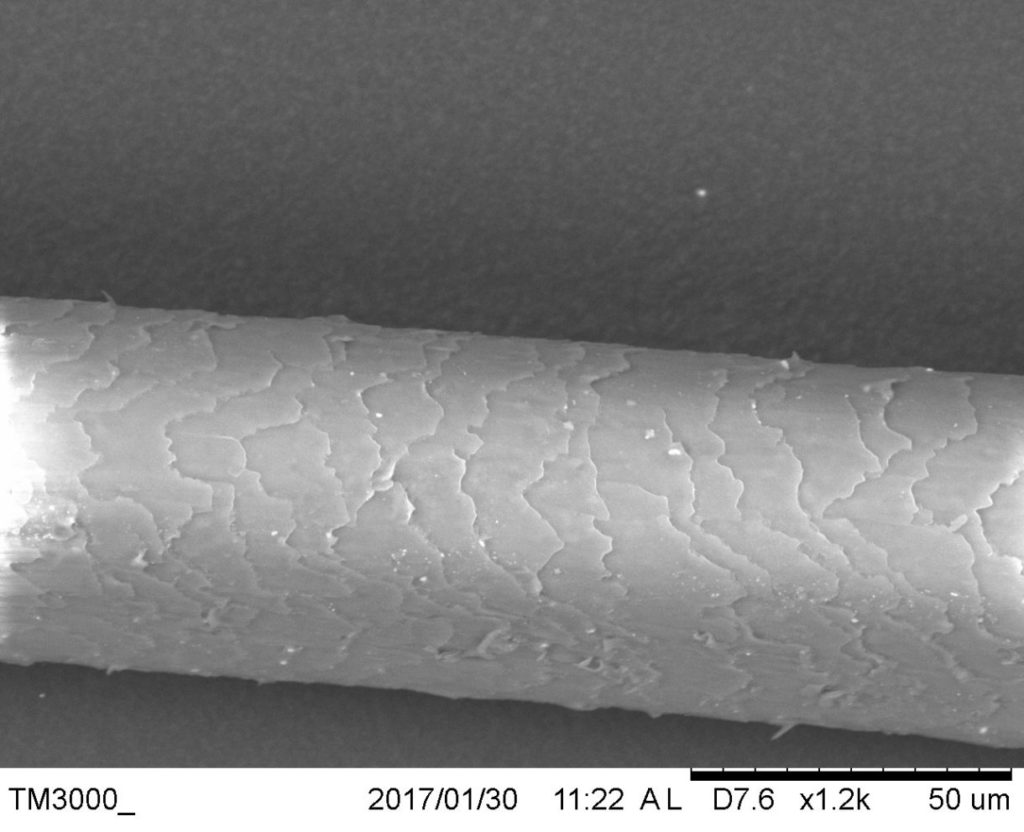

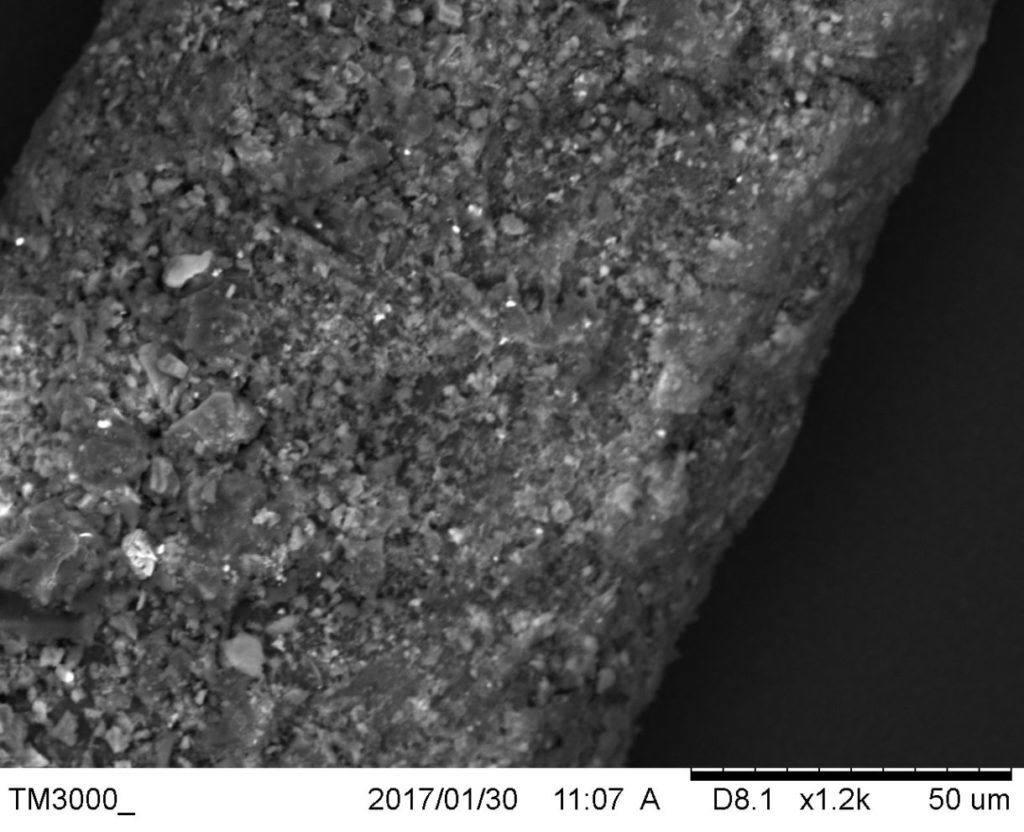

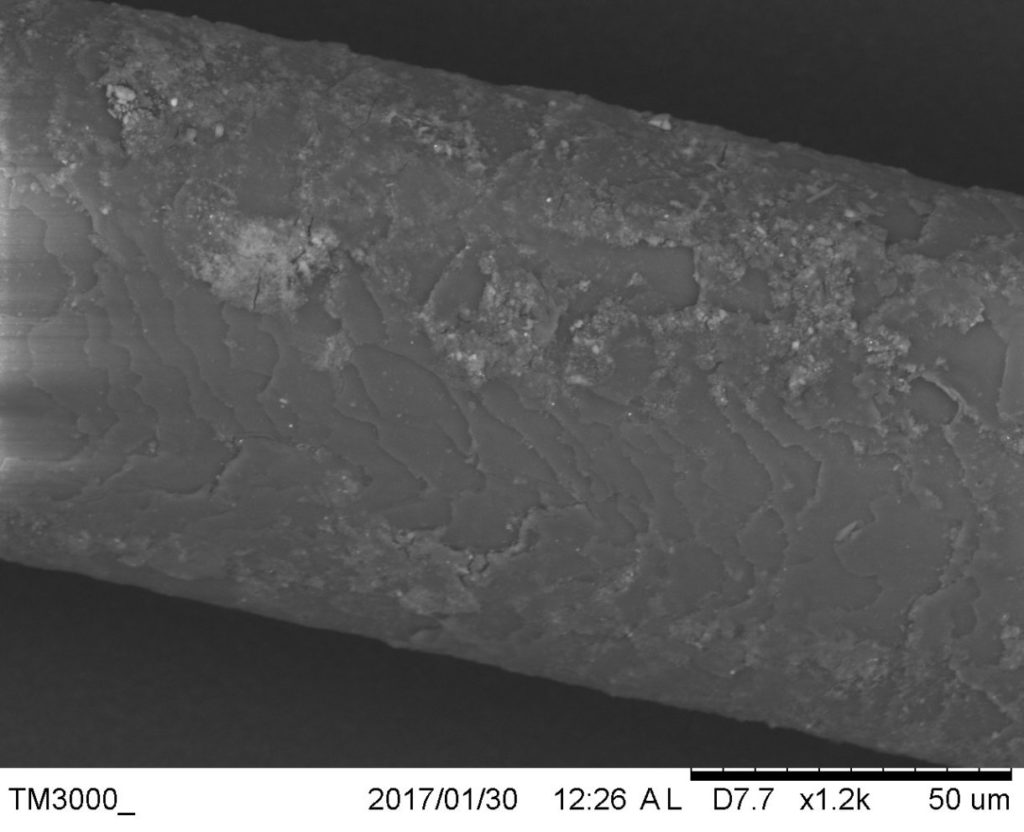

Unlike teeth, it is very difficult to identify what species a strand of hair came from with the naked eye. The hair on the sword was very brittle, and sadly some small pieces became detached. They were not wasted however! They were carefully collected and taken to Durham to undergo scanning electron microscopy (SEM). This is a very powerful technique, which can magnify an image over 1000 times and allows us to see the scales that make up all hair in a unique pattern to each species. My first attempt was unsuccessful due to a build up of ethnographic and museum dirt obscuring the hair surface. However, after cleaning, the pattern of scales was revealed, and when compared to a known sample of human hair (taken from my own head!) it was clear that this was human hair.

So where does this leave our sword? Well, some questions answered, but new ones created. And so life goes on as usual in the conservation lab!