The Fitzwilliam Museum’s Miranda Stearn, Head of Learning, and Ruth Clarke, Learning Associate, Inclusion, attended the Culture, Health and Wellbeing International Conference in Bristol. Here they reflect on conference highlights, memorable moments and unexpected situations.

Billed as a ‘showcase of inspirational practice and policy’, this conference was a great opportunity for the Fitzwilliam to reflect on, and help develop, the Museum’s and wider University of Cambridge Museums’ role in the realms of health and wellbeing, building on and taking forward our successful partnership programmes with, for example, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Dementia Compass and Arts in Mind.

Inspiring examples of work

Miranda:

I attended a few sessions delivered by dancers and dance movement psychotherapists working with people with a dementia diagnosis and also with Parkinson’s. I was struck by the way practitioners articulated the benefits in terms of motivation, joy and shared experience that dance brought, in the context of people’s highly medicalised lives. I was struck by this quotation, shared by dance movement psychotherapist Dr Richard Coaten, from the wife of a person with Parkinson’s: ‘People with Parkinson’s are often involved in numerous therapies to try and improve the movement problems caused by the condition. On a bad day, or even a good day, it is extremely hard to be enthusiastic or motivated to do the exercises; but dance to music, with others sharing the same, has a transforming power like no other.’ I was also struck by Danielle Teal’s presentation on the value of artistry in dance and health practice, a warning against falling into formulaic approaches when practitioners understandably repeat what works elsewhere rather than rooting their dance and health work in the integrity of their own developing creative practice, and vice versa. I found these examples particularly helpful as I think through what we are learning from our own recent work with dance at the Fitzwilliam Museum.

I enjoyed hearing Marilyn Lajeunesse from Montreal Museum of Fine Art as part of a session on mental health and creative practice. I was particularly struck by the pride with which she described her museum’s art education spaces as the largest in North America, with 3555 square metres of space devoted to education and art therapy, including multi-functional spaces, a lunchroom, and also 12 workshops suitable for art therapy. This sense of creating spaces for art therapy as part of the regular functioning of the museum was inspiring. At the Fitzwilliam, we have begun hosting art therapy sessions delivered by our partners from East Anglia’s Children’s Hospices (EACH) and this has led to conversations about what is different about doing art therapy in a museum, for the participants and the practitioner, and also the impacts in terms of how the participants feel about the museum.

Ruth:

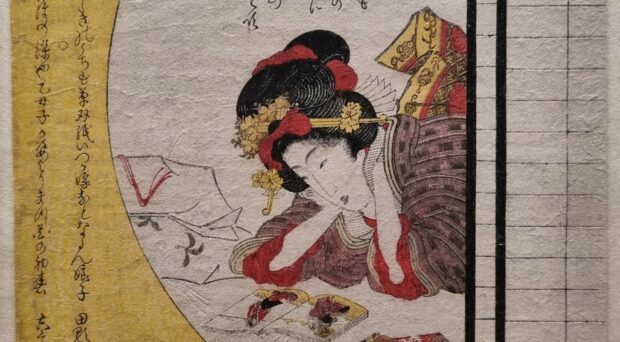

The University of Bath and Bristol Touch Diary dance and wellbeing research project resonated with me. We are currently piloting a project called Dance at the Museum, working with Cambridge artist Filipa Periera-Stubbs. Here older people are joining us in the Fitzwilliam to explore art together, select music in response, and dance! Hearing about the Touch Diaries helped me to consider the embodied emotional and intellectual qualities of this experience. Touch runs throughout the work, whether that be touching each other, touching the space or being in touch with what’s happening (or not). As such our sense of touch becomes almost a conductor for our sense of connection or interconnectedness, a central idea in wellbeing – an idea that is extended in the project to connecting to culture and art; potent combinations indeed!

Many of us are familiar with art being on display in hospitals and may appreciate how the artworks help us find our way around the endless corridors or take us ‘somewhere else’ and / or simply help to make the environment less clinical, less scary, more human. The Australia Institute for Creative Health shared two pieces of art from their hospital art residency programme (designed to help patients deal with and process their experiences). The first was a piece centred around a life-size zebra, separated from her ‘tribe’ – an emotive representation of the experience of displacement which can be felt when we are unwell – and the second was an artwork that responded to the questions ‘what does art look and feel like? ’ which featured ‘an enormous doodle’ (described as a great distraction!) and a beautiful, intriguing mind map visualising the mental connections we make during ill health.

My response to these bespoke works was a desire to understand more about the opportunities that art commissioned for specific environments create as opposed to art that is curated (for experiencing in that environment). Naturally my thoughts then progressed to whether we could explore this further here in Cambridge through our partnerships, and if our current work at the University of Cambridge Museums, where we are taking museum collections to the Addenbrooke’s Hospital Dialysis Unit, ‘Curiosities at the Bedside’ could be an opportunity to start this exploration moving?

Memorable conversations

Miranda:

I enjoyed exchanges with the other panel members, and delegates, at the social prescribing session I was part of. Social prescribing is a mechanism for linking patients with nonmedical support within the community, and I was sharing the University of Cambridge Museums HLF-supported partnership project with Cambridgeshire charity Arts and Minds, Arts on Prescription, Heritage for Health. It was great to talk to Yorkshire-based Creative Minds about their emphasis on co-production and empowerment, and also really helpful to discuss the findings of a feasibility study for using an arts of prescription approach with pupils in secondary schools in Cambridgeshire – not least because I know we are working in some of the same schools using engagement with our museums as a starting point for activities to raise confidence, engagement and potentially attainment. I was pleased that our panel presentations provoked questions, discussions and sharing practical examples from the audience, some of whom were involved in similar work which we in turn could learn from. At the end of the session, the Chair invited people to call out words to capture their impressions: ‘Hopeful; Expertise; Joyous; Inspiring; Compassion; Complex; What next?’

Ruth:

I also enjoyed a conversation about social prescribing with a seasoned research and evaluation specialist who, through her various pieces of work, had identified what she felt was a key ingredient in having a positive impact: immersion leading to distraction! Whether that be through socialising, being somewhere new and different or being immersed in creative or physical activity, the act of being distracted creates an often much-needed gap from the thoughts or feelings that are haunting us, making space for new emotions, ideas, connections and experiences. She wasn’t of-course saying that there wasn’t a great deal more going on in the process, but was simply identifying that as a key idea this could be helpful for those in the sector when we are working so hard to make a difference.

Potent thoughts and ideas

Ruth:

Dr Iona Heath’s keynote on day two, Cultural Literacy and the Care of the Dying, was in effect a poignant meditation on the importance of being present to all of life. Iona drew on the work of writers and artists whose practice explores death, and drew this together with her own experience in her north London practice. The section of Philip Larkin’s poem Audobe that she shared with us struck me especially, leaving me with the question ‘Why isn’t there more out there, more creative work, shared thinking etc. about the common human experience of connecting with mortality in the middle of the night, when the distractions of the day aren’t present?’:

Waking at four to soundless dark, I stare.

In time the curtain-edges will grow light.

Till then I see what’s really always there:

Unresting death, a whole day nearer now,

Making all thought impossible but how

And where and when I shall myself die.

Arid interrogation: yet the dread

Of dying, and being dead,

Flashes afresh to hold and horrify.

Iona Heath’s call in her presentation, that we resist the temptation to flinch from the experience of dying, influenced my choice of the following session: an in-conversation with author Sarah Moss, whose latest novel Tidal Zone examines how a father learns to live with the knowledge of his child’s mortality through her near death. The book asks how we confront the reality that death can happen in the spaces in between what we think is important and then go on to live productive lives, not being paralysed by the magnetism of fear. Sarah talked about the strangeness of our times, how we don’t always have a connected sense of death, shared her thoughts on gratitude and made a call to us to wonder at the presence of life and death.

Miranda:

I’m always interested by international models and so was pleased to hear about current policy and practice in Finland. I was particularly struck by a slide which said ‘The impact of culture on the promotion of well-being and health is recognized at the political, administrative and structural level’. The upsurge in research, practice, discussion and political engagement (in the form of the All Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) for Arts, Health and Well-being) may be taking us in this direction but I could not help feeling England has a significant way to go before we could make such a clear statement.

A place or time at the conference when you felt you might have been in the wrong room

Miranda:

Tricky. I never felt I was in the wrong room, but, attending the conference less than 2 weeks after a significant bereavement, I found myself responding to the insightful and compelling Cultural Literacy and Care of the Dying keynote address on a personal as well as professional level. I also realised I was not the only person doing so. This reminded me that when we undertake projects seeking to address health and well-being in our museums, we often venture into territory that is personal and emotional not just for participants but for staff, and that it is important we are self-aware about this for ourselves, our colleagues and our participants.

Ruth:

I love singing, and singing sea shanties at the top of my voice is one of life’s real joys! So what a happy coincidence when a session I signed up for, that appeared to be a serious academic exploration (of the impact of arts and dementia practice) contained just this – followed, of course, by the serious stuff! For those of us who love to sing we probably know all too well how ‘good’ it makes us feel, so it’s great to see how much research is going on into this and the benefits it yields. The traction being gained feels like a potent force for action; maybe there’s a museum choir project in Cambridge waiting to happen?

An unexpected event

Ruth:

For me this had to be at the Royal West Academy at the end of the first day – a very long, intense, hot day – which was now a much, much, hotter evening. The speaker started her introduction to the evening’s main event, a musical performance composed by Toby Young entitled ‘Life of Breath’, an exploration of people who are isolated and suffering from breathlessness. As the speaker stood up and began to contextualise the work and open its story up to us, the heat of the evening, in the room, overwhelmed her and she was unable to carry on and needed to go outside to recover. Alison Bevan, the relatively new Director of the RWA, wasn’t blind to the irony of the incident highlighting the importance of the Royal West’s capital development project which includes vital improvements to environmental conditions!

Miranda:

For me it was unexpected (though perhaps should not have been) to be able to spend time sharing ideas with so many Cambridge-based colleagues, from Cambridge Curiosity and Imagination, Cambridge Community Arts, Arts and Minds and ARU. It really brought home to me the strength of interest in culture, health and well-being in our city and region, and how fortunate we are to have a vibrant ecology of organisations delivering projects. It also reminded me how important it is for us to be making links, sharing practice and working together where appropriate – something I hope the University of Cambridge Museums will play an active part in enabling.

What hopes do we have for the future of the proposed National Centre for Arts, Health and Wellbeing?

Ruth:

Before the conference I wasn’t aware of how much research there now is in the field of arts, health and well-being, the challenges involved in locating it, with it being disparate and then the additional challenge of stacking up the various pieces, to frame the work we are involved in, frankly an overwhelming task for those of us outside of the research world. My one big hope – and I think we can be confident this isn’t wishful thinking – is that the Centre will effectively hold this for us and make our work here more informed and joined up, with the sum being greater than the parts

Miranda:

Since the conference we have seen the publication of the All Party Parliamentary Group for Arts, Health and Wellbeing’s report, which helpfully brings together examples of practice, evidence and recommendations – one of which is for the creation of this strategic centre. My hope is that it helps us keep moving the conversation, and our practice, forward, stops us starting from scratch and re-inventing the wheel, and moves towards a point where the potential of culture, health and wellbeing work is exciting to the health sector as it is to us in arts and museums. I look forward to thinking through its implications for us locally with colleagues and partners in Cambridge and the region. As a city known for the innovation of its health research and the richness of its cultural offer, we should be exceptionally well-placed to join our expertise to understand how cultural engagement can make the best difference to those experiencing ill health.

Read more about the All Party Parliamentary Group for Arts, Health and Wellbeing and the report Creative Health:

http://www.artshealthandwellbeing.org.uk/APPG

http://www.artshealthandwellbeing.org.uk/appg-inquiry/

Photo credit: Dancing at the Museum by KJ Martin