One of the many exciting and interesting aspects of being a museum curator is the opportunity to enhance and develop the collections by acquiring new works of art.

You may have heard about the Fitzwilliam Museum’s intriguing recent acquisition of Jean-Léon Gérôme’s (1824-1904) striking portrait of his brother Claude-Armand, painted around 1848, which involved a significant public fundraising campaign; but we have, at the same time, continued to add to our collections of works on paper in interesting and fascinating ways.

What have we acquired recently and what types of works are we looking for?

Since the Fitzwilliam Museum’s foundation in 1816, the collection has significantly expanded from Lord Fitzwilliam’s initial bequest to one that now amounts to over 500,000 objects. The collections within the Department of Paintings, Drawings and Prints have been slowly accumulating over the past two centuries by means of bequests, donations and purchases. Currently, this wide-ranging collection includes over 1,700 paintings dating from the thirteenth century through to the present day, over 16,000 works on paper (such as drawings and watercolours) and around 140,000 catalogued prints, with many more still to be catalogued.

So, what are the factors that determine why an object might enter the collection?

There are important issues to consider and questions to ask:

- Is the object in good condition and is it possible to display it?

- How big is it and can it be stored if necessary?

- If being bequeathed, what are the conditions of the bequest? For example, can it be lent outside of the museum, or does it need to be on permanent display?

- Does it have a clear, traceable provenance (history of ownership)?

- If being offered to the Museum at a price, is this its true value?

Once these questions have been addressed, all acquisitions are required to be presented to the Museum Syndicate, a governing body of fourteen men and women, known as Syndics, who are required to decide on behalf of the University as to whether or not gifts and bequests should be accepted or declined. When these decisions have been made, the new objects are given accession numbers and accepted into the permanent collection of the Museum. As such, the Museum collection as we see it today is the product of decisions made by Syndics, directors and curators, past and present.

New arrivals

Drawings, watercolours and prints by Giovanni Boldini (1842-1931), Marcellin Desboutin (1823-1902), Jess Shepherd (b.1984) and Celia Paul (b.1959) are among works that have recently entered the Museum’s collection. Keep reading if you want to learn more about them and how and why they came to be here.

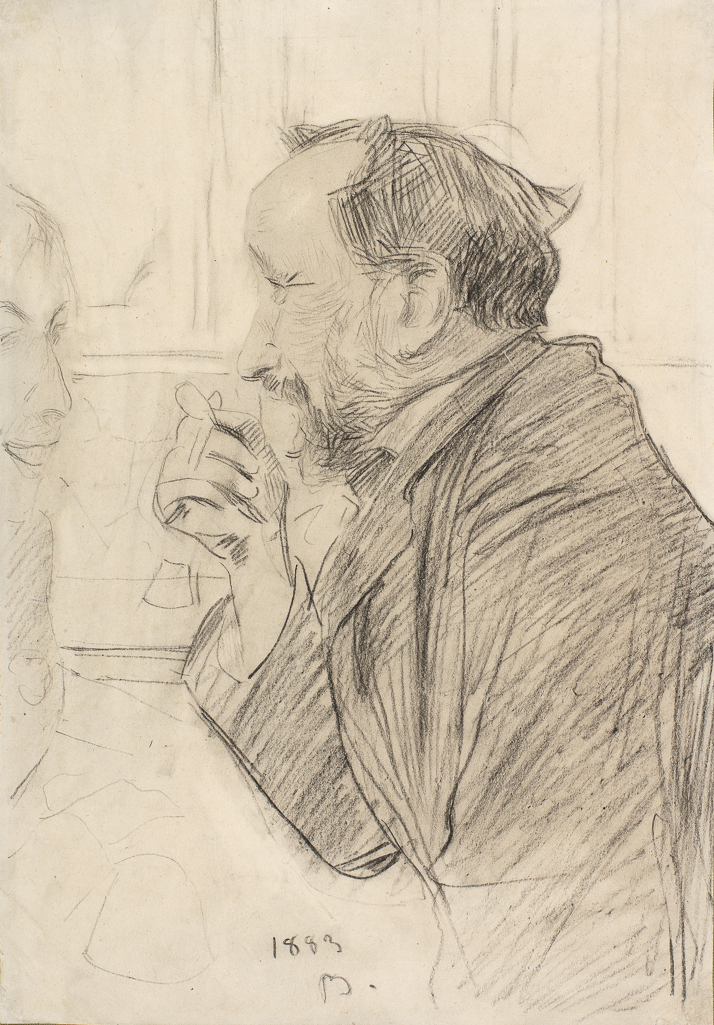

Giovanni Boldini

Acquired in the centenary of Degas’s death, this remarkably animated portrait shows Degas in full conversational flight at a café table. His female companion looks on intently, evidently entertained. Degas was known as a ‘dazzling conversationalist’ who always had ‘substance’ to his conversation. Witty, caustic and given to memorable turns of phrase, he was also capable of shocking his models with racy anecdotes that would ‘make a trooper blush’. In his own work, Degas treated the subjects of cafés and café concerts throughout his career, often focusing on the enigmatic exchanges between its clients.

Born in Ferrara, Boldini trained in Florence later moving first to London, then, in 1872 to Paris, where he became a friend of Degas. He worked mainly as a fashionable portrait painter, his swishly elegant style attracting a wide clientele. His portrait drawings of close friends, however – many of them fellow artists – are more idiosyncratic and characterful, sometimes, as here, bordering on caricature.

This drawing is now on display for the first time in our major exhibition Degas: A Passion for Perfection (until 14 January 2018).

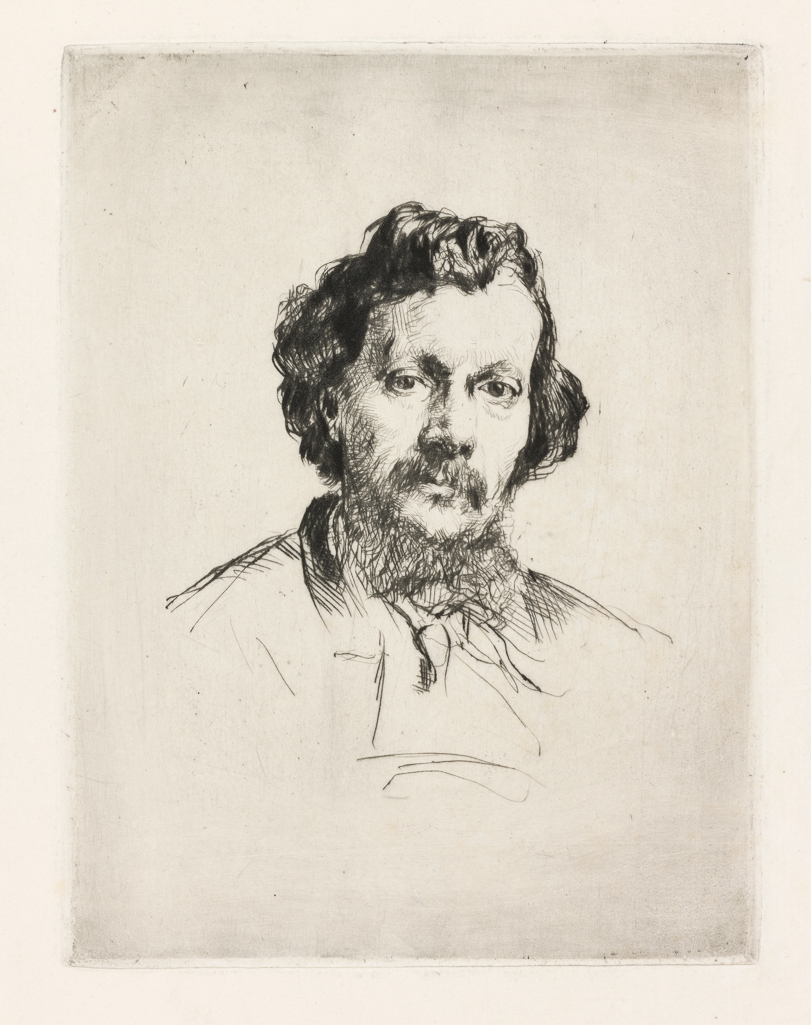

Marcellin Desboutin

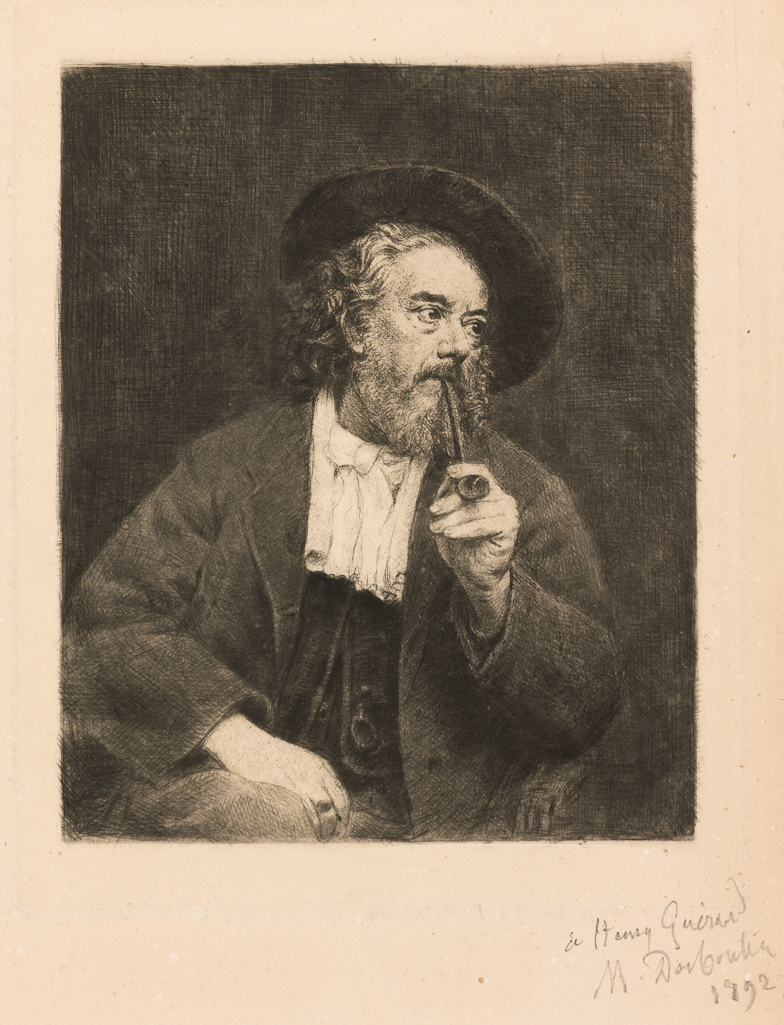

This year the Museum acquired three prints by the painter and printmaker Marcellin Desboutin (1823-1902). The self-portrait is one of many made by Desboutin and this impression is distinguished by the handwritten dedication to the experimental printmaker Henri Guérard (1846-1897).

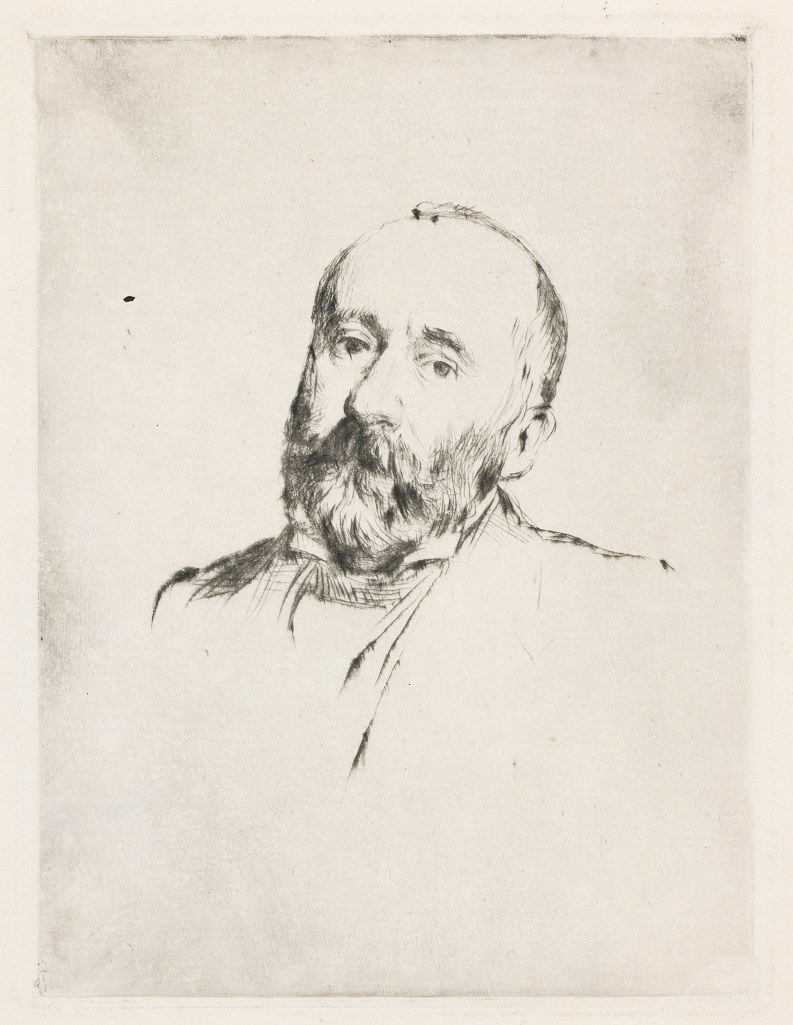

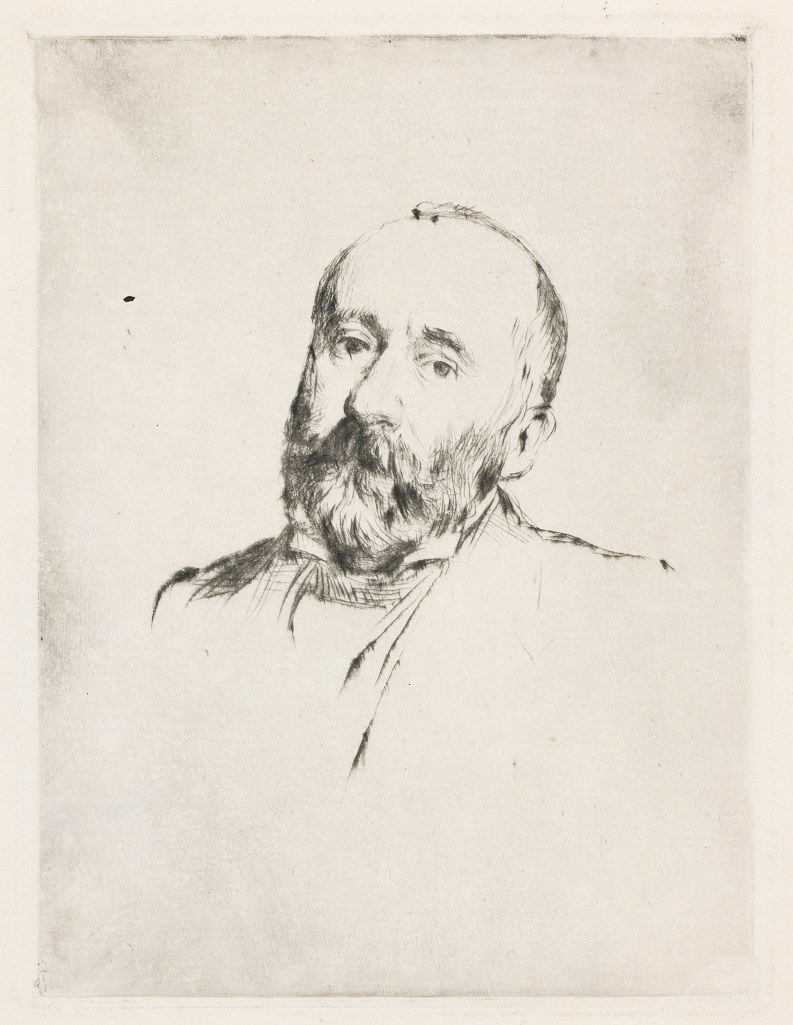

Donato Esposito also donated a portrait of the painter, and lifelong friend of Desboutin’s, Pierre Puvis de Chavannes (1824-1898).

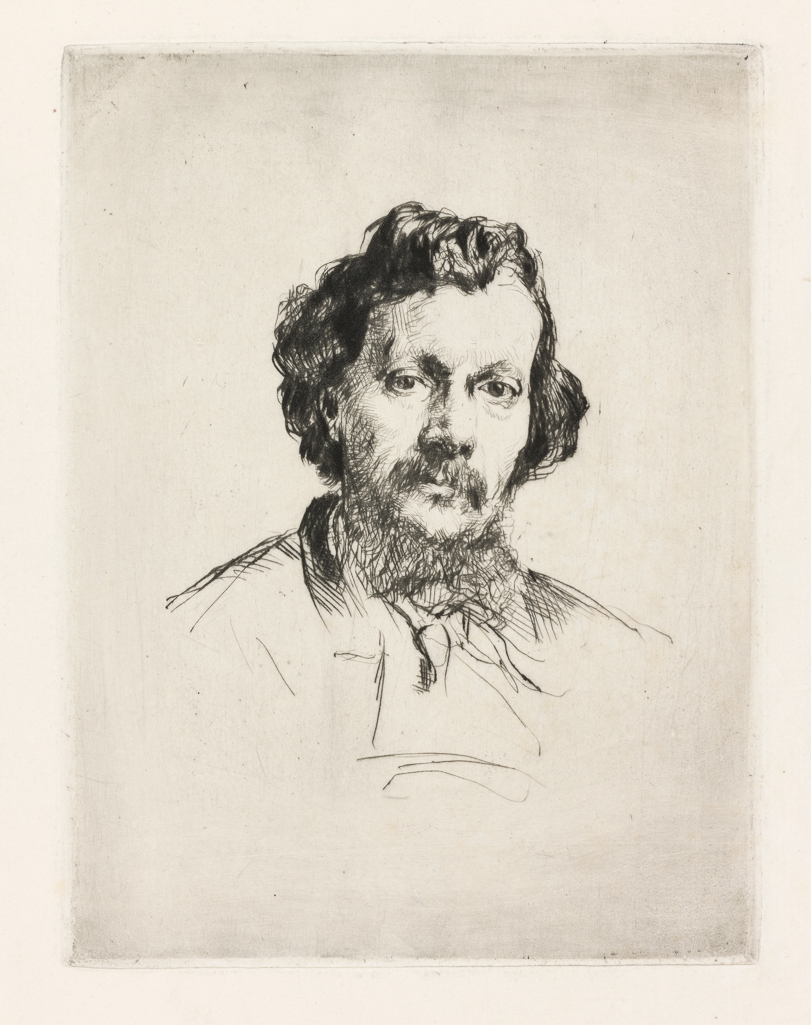

Desboutin was an important contributor to the etching revival in the mid-nineteenth century, as was the print dealer and publisher Alfred Cadart (1828-1875), founder of the Société des Aquafortistes, a group dedicated to the creation of original prints. Desboutin’s portrait of Cadart, made from life, is a particularly fine impression and shows how Desboutin carefully wiped the printing plates to create areas of tone on the surface of the print, a technique Rembrandt had used in the seventeenth century.

All three prints are included in the exhibition Degas’s Drinker: Portraits by Marcellin Desboutin (until 25 February 2018, Charrington Print Room) which displays, for the first time, the Fitzwilliam’s exceptional collection of drypoints by the artist and friend of Degas. This exhibition coincides with Degas: A Passion for Perfection.

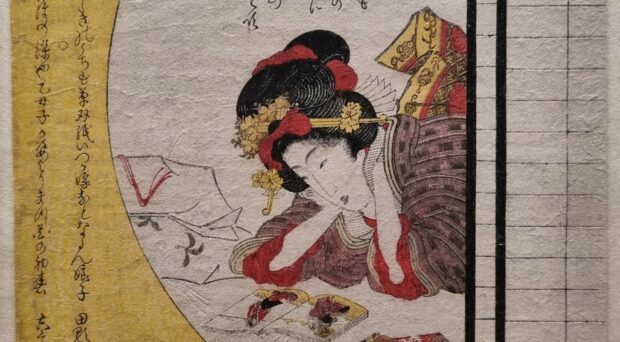

Jess Shepherd

The Fitzwilliam has an outstanding collection of botanical art. This includes over 130 paintings, over 1,000 works on paper, many albums and floral miniatures by artists such as Jan Brueghel the Elder, Jan Davidsz. de Heem, Pierre-Joseph Redouté, Nicolas Robert, Georg Dionysus Ehret and many more.

Much of this collection was bequeathed by Henry Rogers Broughton, 2nd Lord Fairhaven in 1973; his generosity transformed the Museum’s holdings and the botanical collection is now of international significance.

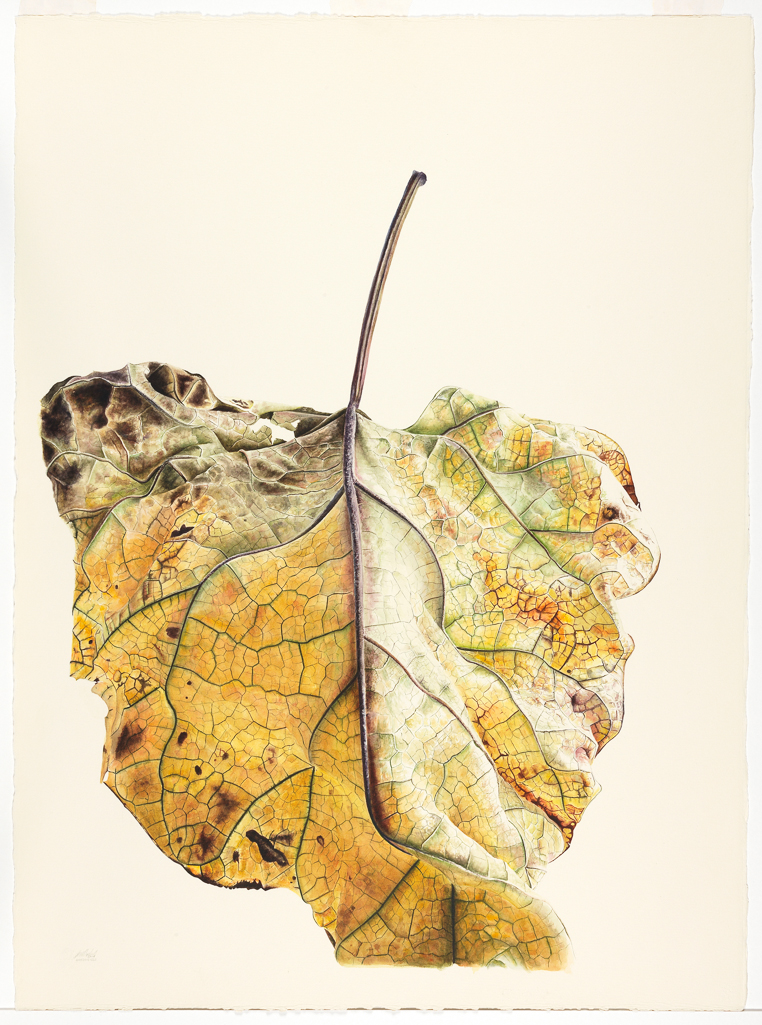

To complement this area of the collection, we have recently acquired a work by the leading botanical artist Jess Shepherd.

Working in watercolour, Jess Shepherd’s oversized leaves are marked out by their extraordinary hyper-realism. Indian Bean Tree comes from a series which includes English Oak, Horse Chestnut and Poplar. Some of the leaves depicted are crumpled and on the verge of decay. Recently exhibited in Leafscape at Abbott and Holder, London, the title of each work records the date, time and location of the leaves. Shepherd also made sound recordings in situ for each of the leaves in the series. To better understand the processes and science of plants she became a student of botany, stating that, ‘When I paint plants I try to become them. […] I believe that a good picture is made using not only sight, but also touch, sound, smell and movement. One has to be aware of all of these elements in order to portray the plant well and describe the space that the plant is growing into, both over and underground.’

Celia Paul

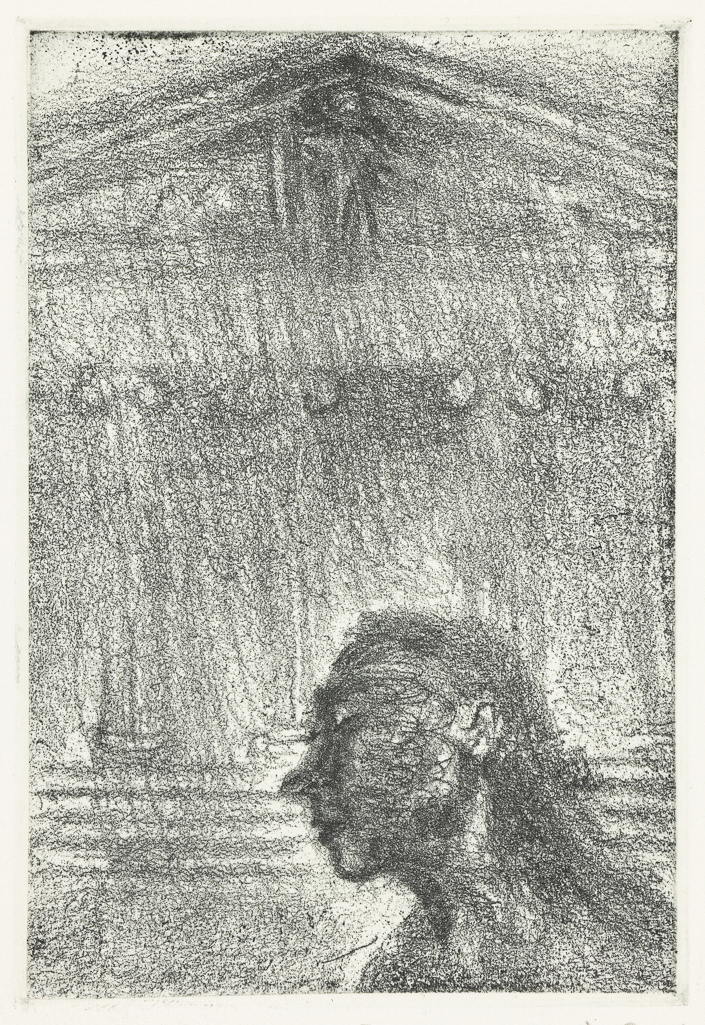

Self-Portrait In Front of the Museum was presented to the Fitzwilliam Museum as a gift from the artist and her representative, Adam & Rowe, in December 2016. The print is from a series of ten soft-ground etchings which were first shown in the exhibition, New Prints & Small Works on Paper held by Adam & Rowe at Enitharmon Editions, London in March 2015. The prints were displayed alongside a number of pencil drawings and watercolours, including other self portraits and sketches of the River Cam in Cambridge where Paul’s mother lives.

Self-Portrait In Front of the Museum is one of several in the series to feature views from the window of the artist’s London studio which is located directly opposite the British Museum. The studio was bought for her in 1982 by Lucian Freud, Paul’s tutor at the Slade School of Art and the father of her son, and Paul has remained here ever since. She has remarked of the location: ‘I’ve lived in this flat longer than I’ve lived anywhere. … I’m directly opposite the main gates of the British Museum and I’m in a constant relationship to it – the visitors walking into it in the day and the lovely creaking of its gates at night when one of the night workers leaves.’

This small print features the head and shoulders of the artist, silhouetted in profile to the left, against the backdrop of the grandiose south entrance. The circular projections of the ionic capitals of the colonnade, the steps and a figure relating to the representation of either art or science in the pediment above, are outlined in darker tones, but the central area is soft and fuzzy as if viewed through rain.

In soft-ground etching, the printing plate is covered in an acid-resistant mixture containing tallow which remains wet or ‘soft’ for long enough to enable drawing onto paper placed over the surface. The removal of the soft ground through drawing and pressing then exposes the plate to the ‘bite’ of the acid and creates the lines seen in the final print. Paul’s use of a rough-textured paper, as is the case in all the prints in the series, has created the grainy atmosphere visible throughout.

Paul favours soft-ground etching for its immediacy and she has declared of the medium: ‘What I love about soft ground etching is that I do them quite quickly and yet the acid works on them like time’.

Self-Portrait In Front of the Museum is one of two prints by Celia Paul in the Fitzwilliam collection.

Catch them while you can …

Some of these recent acquisitions are already out on display in our current temporary exhibitions, Degas: A Passion for Perfection (until 14 January 2018) and Degas’s Drinker: Portraits by Marcellin Desboutin (until 25 February 2018, Charrington Print Room).

Further study

Due to the fragile nature of works on paper and their sensitivity to light they cannot be on permanent display. However, you can make an appointment to view any of the works on paper from our collection in the Graham Robertson Study Room, which is open from Tuesday-Friday, 10am-4.30pm (closed 1-2pm).