I was fortunate to be invited to attend the launch of the new Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) / Royal Society of Arts (RSA) Learning about Culture Programme on Tuesday 17th October. In this post I reflect on the programme and consider what arts and cultural organisations can do to improve the evidence base around our work with children and young people.

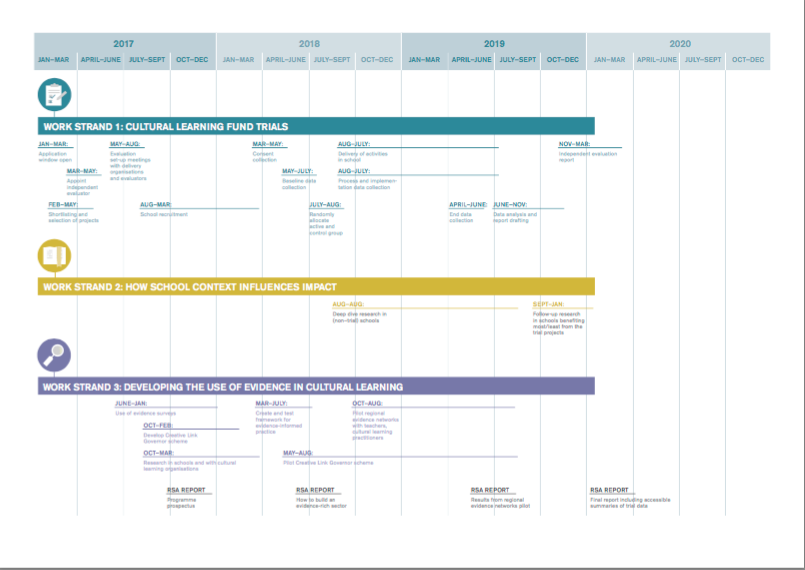

Work Strand 1: The RSA/ EEF Randomised Control Trial Project

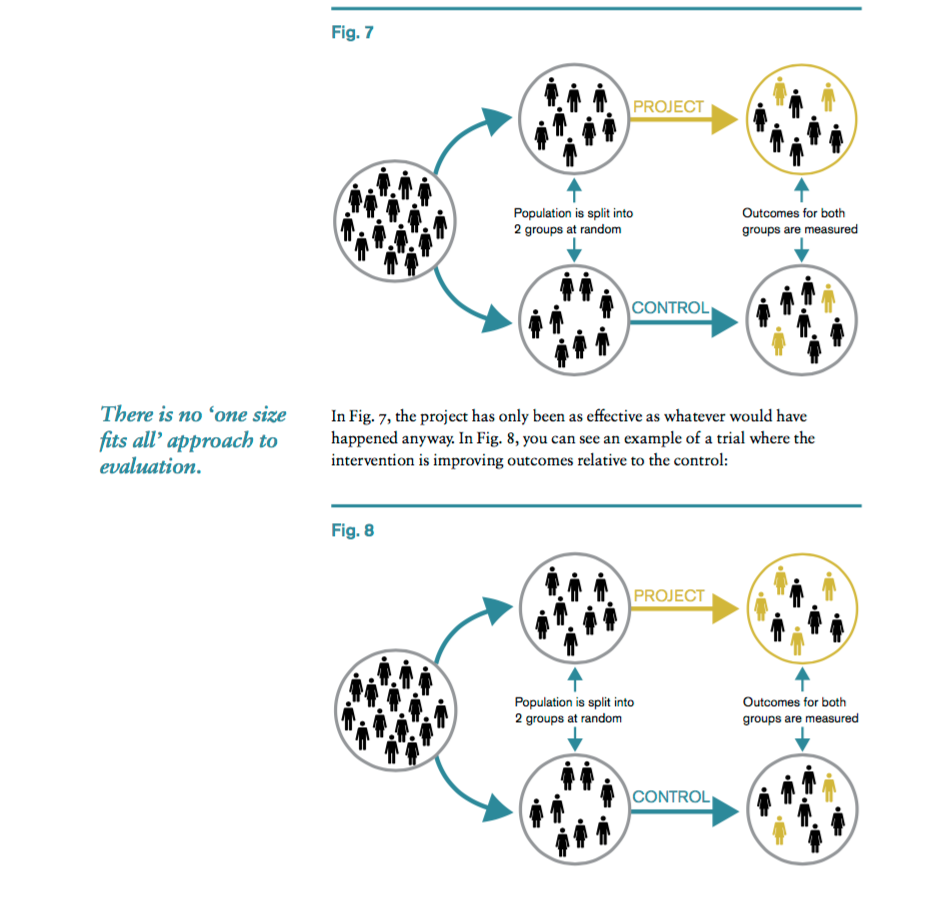

The first work strand of the RSA Cultural Learning Programme will involve running randomised control trials to test 5 projects which are designed to support attainment in reading and writing as well as other skills such confidence, motivation, and self-efficacy. According to the project prospectus, a randomised control trial ‘involves randomly assigning from a group of potential participants, which children and young people receive the treatment and which do not’, as the image below demonstrates.

At the launch event, we heard from Speech Bubbles, one of the selected projects. This is a primary school drama intervention which supports children’s communication skills, confidence and wellbeing. Adam Annand described how their ‘evidence journey’ started back in 2006 with a Research and Development grant from the Arts Council and a project involving 18 Lewisham schools. Robust evaluation methodologies were built into the project from the outset and their working process has evolved in consultation with schools, speech and language specialists and researchers and academics from Canterbury Christ Church University, Project Oracle and Birkbeck, University of London. This impressive and rigorous approach has enabled the project team to interrogate and gather evidence on the specific effects of their programme. This must have provided a compelling case to EEF and RSA when selecting projects to be tested.

Measuring What Matters

I am very interested to see what the results of the EEF trials will be and I hope that all projects will make a demonstrable difference to the children they work with. However, I question the appropriateness of measuring improvements in attainment in reading and writing as the best way of demonstrating the value of cultural learning to schools, teachers and funding bodies. Emily Pringle’s blog post unpicks some of the value judgements implicit within the RSA/EEF project which can be seen to privilege attainment in literacy over the arts and what this reveals about the current subject hierarchy. This might be in part due to a perceived difficulty in recruiting participants for randomised controlled trials from schools and teachers under increased pressure to deliver. Geoff Barton describes the current climate as, ‘an accountability system that measures success chiefly on a narrow range of academic subjects, and a funding crisis that makes smaller subjects difficult to sustain.’ The absence of secondary projects within the project is also disappointing at a time when arts subjects are under decline, as demonstrated within the recent Education Policy Institute report on Entries into Arts Subjects at Key Stage 4. Many schools and teachers look to their local arts and cultural organisations to support them to ensure that the children they teach continue to have access to high quality arts provision as the curriculum is increasingly squeezed, as demonstrated by the growth of local Cultural Education Partnerships such as My Cambridge.

Work Strands 2 and 3: Digging Deeper and Developing the Use of Evidence

Alongside the EEF projects, the RSA are also planning at third strand of activity to support arts and cultural organisations to develop high quality research and evaluation and to encourage practitioners to think about how they use evidence, both for advocacy and to improve both practice and effectiveness. This was in response to the quality of evidence demonstrated in the applications to the Cultural Learning Fund Project when it was launched last year. Since then, the RSA have surveyed the sector to better understand the existing state of evaluation practices and found that only 40% have a Theory of Change in place to enable them to demonstrate how their activities might lead to change. We had representatives from Speech Bubbles and The Young Journalist Academy, two of the selected projects, on our table and I was impressed by how they talked with passion about working in partnership with schools, teachers and young people to develop programmes and evaluation tools which responded directly to their needs and concerns. This seems to be a really good way of ensuring that we measure what really matters. The second work strand of the project involves digging deeper into the schools context to look at how that also influences the impact of 5 projects.

Photo by Martin Bond.

Reflections

Since I attended the event, I have been thinking about what museums and galleries can achieve within their programmes for schools. The majority of the projects selected for the randomised control trials offer repeated activity or training over a period of time. The majority of schools that visit their local museum or gallery do so for a couple of hours every year, and perhaps only once over 7 years of primary school. Although projects such as the UCM Arts Award programme and strategic school partnerships enable us to work in a more sustained way with groups of children and young people, this only represents a small proportion of the thousands of school children who visit us every year.

In our role as an Arts Council-funded Major Partner Museum we were pleased to be able to take part in piloting the Quality Principles and Quality Metrics in recent years. However, we need to differentiate between different kinds of evidence and be clear that the evidence we collect should be dependent on the questions we ask. This is another important point Emily Pringle makes in her blog post. Randomised control trials are only one method for assessing and evidencing the changes that cultural programmes can bring about. It would be good to see more high quality qualitative evidence within the sector too and a greater acknowledgement of the value of collaborative and arts based practice research as demonstrated in the interdisciplinary Connected Communities Project and many of the projects highlighted in the Cultural Value Project.

What next?

Although there is lots to reflect on, I left the event feeling encouraged by the shared commitment to developing quality evaluation and research within the sector. The RSA project represents a tremendous opportunity for us to work together to understand how to better evidence what we do, and it will be interesting to see how it links up with the work on creativity and education that the Durham Commission is also undertaking.

I hope that there will now be more opportunities to share good work many of us are already doing collecting a variety of evidence around our programmes which reflects the range of activities we undertake with our different audiences. At the University of Cambridge Museums we are currently developing practitioner-led research through a series of residency projects designed to encourage closer collaboration between universities, teachers, museum and garden educators, and children and young people. We are also working on developing automated systems to allow us to collect both quantitative and qualitative data, in partnership with colleagues from the National Gallery and a team of social scientists from Warwick University in an AHRC Cultural Value Follow On Funding Project. One of the project outputs will be a series of case studies sharing our experiences more widely in end-of-project events next summer. At the heart of this is an evaluation strategy which enables us to not only collect better evidence around the impact of our programmes with children and young people, but also feed this information back into the planning cycle as part of an iterative process.

We will be writing about both of these projects for this blog over the coming months so watch this space!