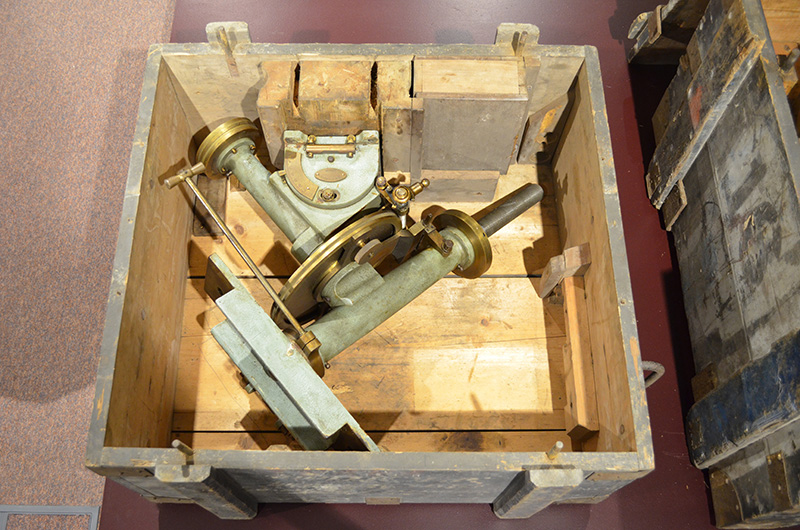

There were crates. That’s all I knew at first. Great big boxes full of scientific instruments sent back from an eclipse expedition sometime in the last century, and never re-opened.

As soon as a colleague told me about them, I’d turned over in my mind the possibility of using them as the centrepiece for an exhibition here in the Whipple Museum of the History of Science. These long-forgotten boxes were a time capsule waiting to be rediscovered, unpacked, and displayed.

First, I had to find them. This, fortunately, was easy. The crates had been sent back to the same place they had come from: the University’s Observatory on Madingley Road. After travelling out to remote locations in the field—Norway; Canada; the Tokelau Islands in the South Pacific—the carefully-packed instruments arrived back in Cambridge in the late 1950s or early 1960s, never to be unboxed. Eclipse expeditions were going out of fashion, and the suddenly unwanted instruments made their way into storage, where they had remained ever since.

Luckily for me (and for the crates), old unused and unwanted instruments don’t disappear up at the Observatory. This is thanks to the hard work and loving attention of Mark Hurn, the Institute of Astronomy’s Librarian. Mark has spent years making time away from his books to find, research, and preserve his Institute’s huge array of old and no-longer-wanted kit. There’s far too much of it to transfer into the Whipple Museum’s collection, and thanks to Mark’s hard work the Institute of Astronomy has among the best preserved and cared-for collections of heritage objects of any department in the University.

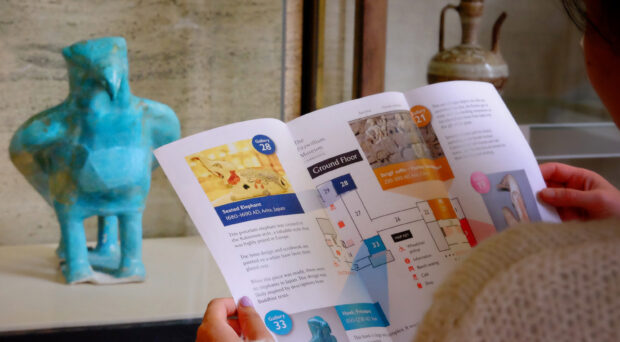

This kind of hidden labour lies at the heart of most good exhibition projects. Curators rarely work with just the objects in their own collections; mounting special exhibitions typically means collaborating with a huge variety of people across multiple institutions. The crates Mark had taken care to catalogue and preserve gave me an idea, which over time and through discussion with many friends and colleagues developed into an exhibition proposal: Astronomy & Empire. Mark’s crates would sit at the centre of the gallery. Around them would be assembled an array of objects that, like the eclipse expedition tools, illustrated and evoked the close relationship between astronomy and the conquest and maintenance of the British empire. This is a complex and challenging story, which brings together a range of scholarship from the Whipple’s parent Department—History and Philosophy of Science—and beyond. Time and again, the way in which we put the final exhibition together was shaped and re-shaped by collaborators like Mark; like the many scholars in Cambridge who gave their time to discuss the displays; like the colleagues at other museums who worked to loan and help interpret objects.

It is a common mistake now to see ‘curating’ as merely the act of selection—the lumping together of a few choice things picked out of a big pile, in the manner of a listicle or a department store window. But what museum professionals and their collaborators do is never this simple or limited. Above all, curating is a process of knowing—knowing a collection, what’s in it, how to interpret it, and how it might have meaning to others. This kind of knowing is necessarily collaborative, and it requires a broad range of special expertise on the part of all those involved: curators, conservators, historians, collections managers, exhibition coordinators, learning specialists, and collaborators like Mark Hurn. Working together, objects are not just selected—they are found, preserved, catalogued, conserved, researched, interpreted, and displayed. They are known, a truly collective enterprise.

Astronomy and Empire runs until 28 September 2018.

Watch a short video about one of the objects in the exhibition here.