In May 2018, four museums/services came together to share with the sector their learning through participation in Sensing Culture, a three-year (2015-18) Royal National Institute of Blind People (RNIB) initiative designed to improve museum access.

Ruth Clarke, Inclusion Associate from the Fitzwilliam Museum, shares her top ten tips, thoughts and takeaways from what was a content-rich and thought-provoking event.

The event

The ambitions for the event were ‘to bring together like-minded people’ from across the sector to showcase some really great practice and areas of innovation in order to provoke thinking and seed activity with the aim of helping museums to be inclusive and future facing.

The four participating museums/ services were:

- Arthur Conan Doyle Collection, in partnership with Portsmouth University

- Canterbury City Council Museums, with project focus the Beany House of Art & Knowledge

- Oxford University Museums & Collections

- Sussex Archaeological Society, with project focus Lewis Castle & Barbican Museum

Combined they offered up a broad spectrum of approaches, each having quite different contexts, collections, drivers and opportunities framing their project intentions and activity. There was however a shared theme that ran throughout all their experiences which was get the visitor experience right for blind and partially sighted people and you get it right for everyone. I.e. remove the barriers for one person’s impairment or difference, and very often you are removing them for everyone. An example of this practice that may resonate was the Lewes Castle soundscape which contains sound effects and audio description created to help people experience the expansive view of East Sussex from the top of the castle. The team extended the use of this by embedding it in a bench (with speakers) at the foot of the steep castle steps (no lift) so that ‘all’ members of a group can enjoy and share the experience.

Top ten tips, thoughts & takeaways …

1. Challenging perceptions and beliefs

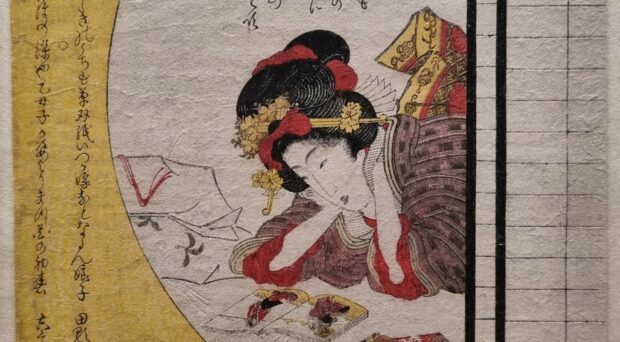

Simon Hayhoe, keynote speaker, opened the conference by sharing Esref Armagan’s story. Armagan, born blind, is an artist who paints and draws using not only colour, but also shadow, light and perspective in his unique imaginative scenes. Armagan didn’t go to school and critically was never told that art ‘wasn’t for him’; he would ask questions about how things looked and his family would describe them to him. His father, an engineer, took him to work and gave him a metal scribe and card to draw creating shapes and textures. Armagan built on this adding colour etc. finally settling on the texture of acrylic paints as his chosen medium. In sharing Armagan’s story Hayhoe was looking to challenge what he describes as the ‘centuries of beliefs about colour … to show that it is possible for people born blind to understand, describe and create visual pieces of art.’

2. Please touch the art!

Museum devices that combine audio and tactile information tend to be tailor-made for exhibits and cost in the region of £10,000 each. Jessica Suess, Digital Partnership Manager at the Oxford Museums, wanted to develop a single device that could stand beside an exhibit to deliver both audio and touch feedback, which could also be repurposed (by museum staff) to make the museum a place where people ‘can turn up and there are things in place, so you can experience and enjoy… just like a person who is sighted. We’re trying to get parity of access.’ The Oxford Please touch the art! resource is currently in its research stage, due to be complete summer 2018.

3. 3D printing

Another area of development at Oxford Museums has been to produce a range of 3D printed objects as handling resources to enhance talks, tours and making activities. This was a new opportunity for the Museums and they were keen to understand more about what the resources could offer and how best to commission them. Feedback from users was clear in positioning ‘the prints’ as interpretation tools. That is, they were not models or replicas -but do offer a sense of shape and form. Also, don’t choose the least expensive options, these tend to have quite an off-putting feel; 3D prints come in different materials, each having its own unique feel! From an organisational angle, the last point Oxford shared was to work with one of the larger, more established companies with their being more likely to respond to development opportunities in the field and offer you the best options.

4: Audio describing, duration?

Lonny Evans, an experienced audio describer for Vocaleyes who had worked with Oxford Museums and Lewes, was keen to emphasise that ‘less is more’ when audio describing. Her recommended maximum time to describe an object was three minutes; after this people can find it hard to retain their concentration if simply listening. For the object to have personal meaning and connection the three-minute threshold is the point at which the describer becomes the facilitator, encouraging interaction, discussion and offering opportunities to touch and for self-expression.

5. Creativity & audio describing

The idea of the neutral voice is one that in effect stops the personality of the describer ‘getting in the way’ of the listeners audio to visual process. The key to an effective neutral voice is to simply describe the subject without adding personal interpretation. This premise is being challenged by some in the sector, who ask whether this can ever really be possible? Coming out of this discussion is a growing trend for interpretation and the neutral voice to be combined; the Lewes castle audio guide noted previously is one such example. In 2017 Shape Arts hosted a series of Tate Exchange session entitled Ways of Seeing Art , which yielded some rich thinking around this topic, the downloadable book from the event being a helpful tool to continue the debate!

6. Inclusive language

Ensuring inclusivity through our use of language is something ‘we’ know is critical. Simon Hayhoe, when asked about best practice in the sector, was keen to emphasise that inclusive language is not non-visual language!

7. Sound tours for all

At Hove Museum (East Sussex), they created an audio and sound tour that was both interpretive and in effect a ‘label reader’. The tour could be accessed using a ‘sound pen’, a simple device that is activated when the ‘nib’ comes into contact with a ‘label’, a plastic pre-programmable button or a raised area (depending on the brand). To open up this experience to all and to destigmatise its use the museum has created an interpretation panel and pick-up spot for pens that can be accessed independently.

8. Going off-site

The Arthur Conan Doyle Collection is a paper-based archive with no museum site, thus the project here was very much about taking the collection ‘out’ and in doing so being free of traditional museum parameters. Working with Portsmouth University they made a ‘creative and innovative approach to three-dimensional sensory modelling’ that incorporates different textures as well as heat and vibration. 16 exhibition panels make up a touring exhibition about Conan Doyle’s life with ‘sensory chapters’ embedded within. As a portable exhibition it can be located in spaces that make experiencing it ideal e.g. natural light, comfortable seating etc.

9. Making art

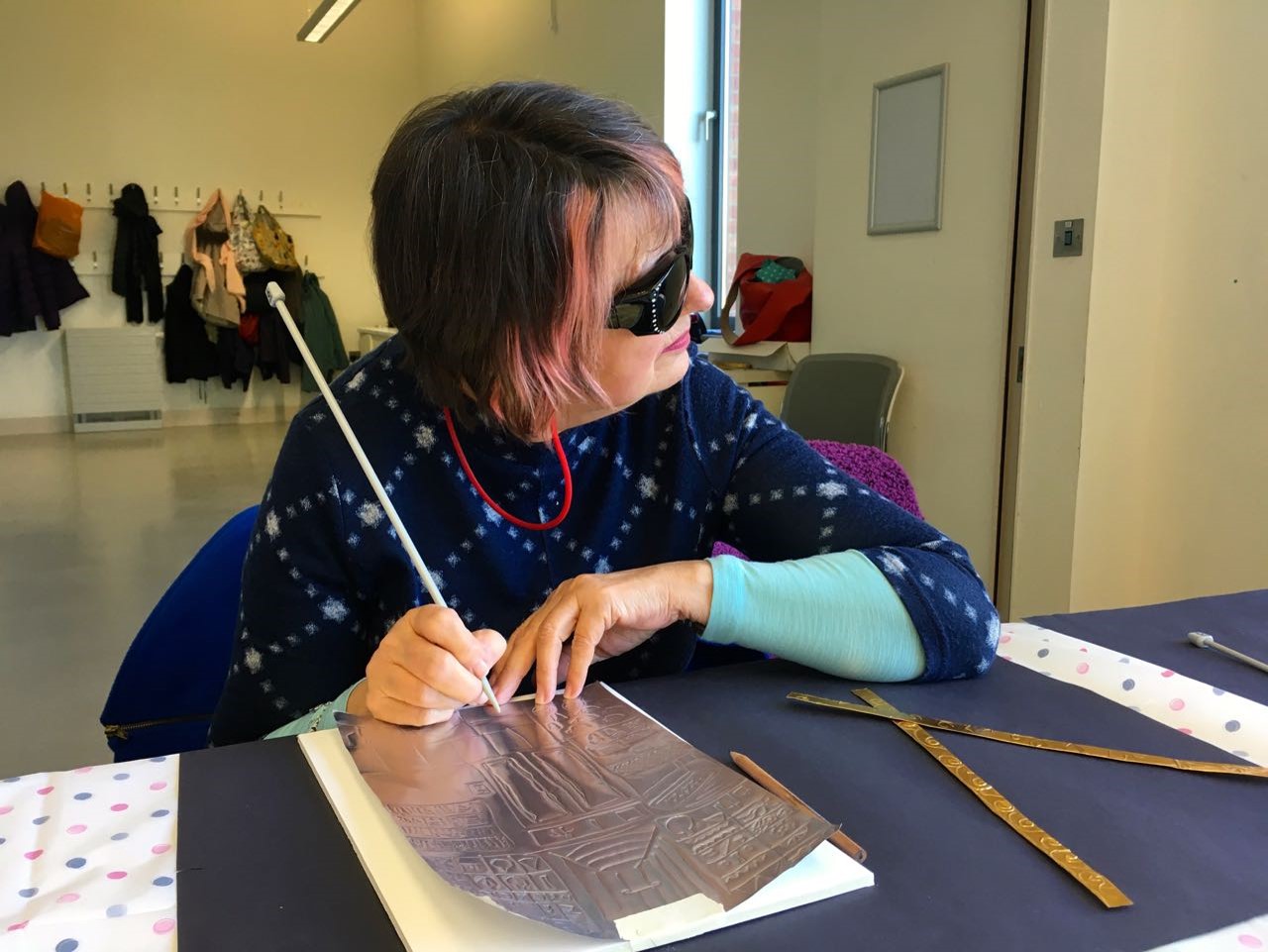

Artist Wendy Dawes developed monthly textile and mixed media workshops at the Beaney, Canterbury, inviting responses to the collection, Canterbury Cathedral and local architecture. The workshops culminated in the Mark of the Maker exhibition in the Beaney’s Front Room Gallery. Wendy facilitated a hands-on session during the conference to share aspects of her approach. These included the use of embossing foil, stitching, mod rock relief imagery, weaving and pipe cleaners!

10. Partnerships

All of the Sensing Culture museums emphasised that critical to the success of the programme has been the partnerships they had formed, nurtured and, now, many deliver in the context of. These partnerships were with local organisations, individuals, the RNIB and beyond. Trust, reciprocity, time and openness were all core ingredients cited by the museums to the success of these relationships.

What are we doing in Cambridge?

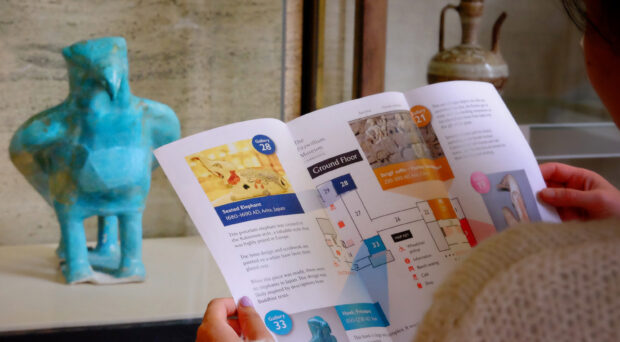

At the University Of Cambridge Museums we have been working on making our museums more inclusive and accessible places with the help of training from Vocaleyes. This has provided staff and volunteers with the skills to lead touch and audio described tours. Accompanying this have been developments in 3D printing, audio guides, raised print / imagery, website information and, pivotally, the ‘museum welcome’, with front of house teams being prepared to ensure that everyone feels that this is ‘a place for them’, for example providing water bowls for assistance dogs if needed. Recently at the Fitzwilliam Museum we have also started to pilot creative workshops on Saturdays for people who enjoy exploring the museum and having the opportunity to make and create. This has extended the audience again to include people who work and those who enjoy learning by experience and self-expression.

The future

The Sensing Culture report concludes with a key message that chimes with the reality that we have a way to go in responding positively to the social model of disability, i.e. that disability is caused by the way society and museums are organised, rather than by a person’s impairment or difference. Working with people to understand how best to do this and then doing it is really the only answer to ensuring that museums fulfil their roles as places for us all to enjoy.

Museums have a responsibility to embrace the opportunities of their collections and to make them accessible and this is entirely doable no matter what your site or staff – Sensing Culture 2018

Find out more on the Sensing Culture website, launched in June 2018.