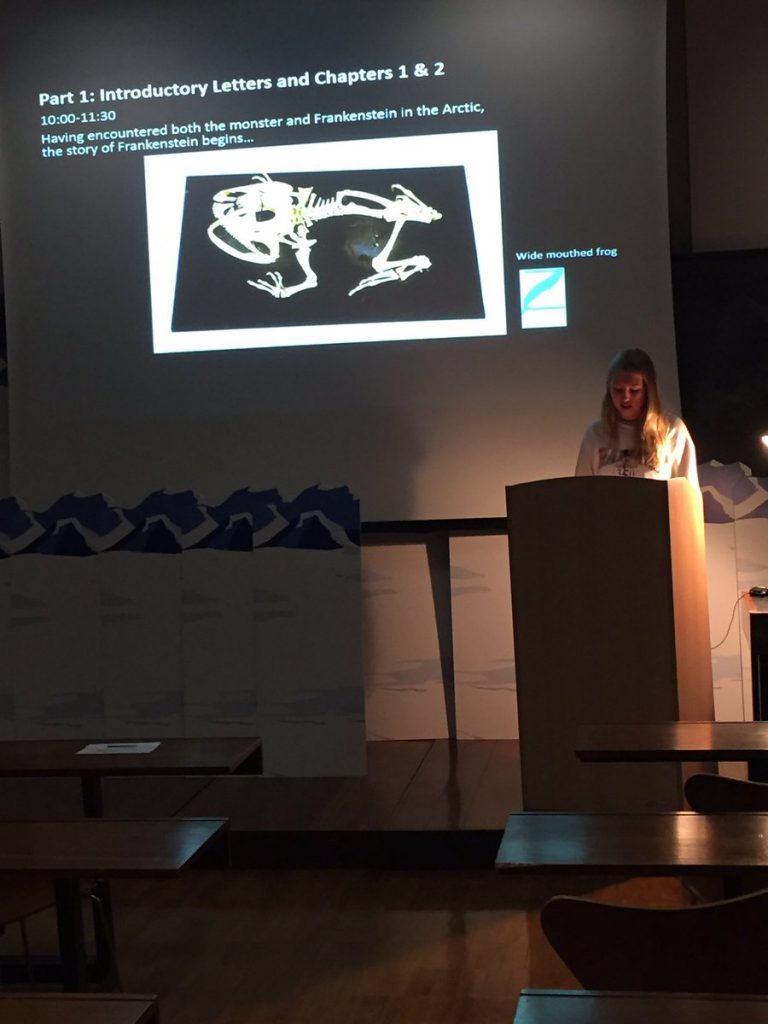

2018 was the 200th anniversary of the publication of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. The book is special to us in the Polar Museum because it starts and ends in the Arctic, which those of you who have only seen film versions of the story might not know.

We wanted to celebrate the anniversary and invite lots of other people to enjoy the story with us. Inspired by the annual Moby Dick marathon* that takes place in New Bedford Whaling Museum every year, we thought a non-stop reading of Frankenstein would fit the bill. With 24 chapters that each take about 30 minutes to read, the book was the perfect length for us to dip our toes into testing a communal reading. We expected the day to be, well, extreme: a long day, but hopefully also a rewarding one where we shared one of our literary greats with new audiences. What we didn’t anticipate was how powerful and moving the experience would be for us and many of the people who braved the stage.

Over to Rebecca Talmy, English PGCE student, who joined us to listen and ended up filling a gap and reading a chapter…

Rebecca writes,

“When I started training to teach English on the Cambridge PGCE (Postgraduate Certificate in Education) course, the Scott Polar Research Institute was not in my mind as a relevant local institution. That was one of the joys of finding myself there for an ‘extreme read’ of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein back in late October, on a day which brought together a whole host of people from different fields and disciplines whose paths might not normally cross. Students and academics from across the English, Education and History and Philosophy of Ideas Faculties; researchers and workers from the Institute itself; and someone else from my course who had told me about the event, all found value in, and took the time to contribute to, the project of reading all 24 chapters aloud in a day.

“A range of different people came together to hear it – I chatted to two and found out that one of them was a student who, like me, needed to read Frankenstein for their course, and the other was a teacher preparing to teach it. Others, I did not chat to and could only speculate about, but I still came away feeling I had shared a communal experience with them. Most people dipped in and out – I was the only person who was there from the beginning to the end (earning me my prized beluga whale keyring!).

“Frankenstein perhaps lends itself particularly well to such an interdisciplinary gathering: it begins and ends with a polar expedition, is preoccupied with fears about the dangers and limits of scientific endeavour and its implications for the relationship between humans and the divine, and is generally recognised as a literary classic. It is not unique in this respect, though: the richness of literary texts is surely a major reason for their prominence on the school curriculum. But struck me as strange to realise that, outside of school and since my parents stopped reading me bedtime stories, this was the first time I had been part of a communal experience of reading prose, and that is probably typical for the vast majority of adults.

“I came to be at that event because I needed to read Frankenstein for a subject studies session looking at teaching a literary classic, but found that it resonated with a wider focus of our subject studies sessions: the importance of speaking and listening within the English curriculum. Our attention had been drawn to Joy Alexander’s call to cultivate students’ capacity to hear the ‘voice’ of texts rather than just experiencing them as words on the page, a distinction I had never consciously considered before. After the ‘extreme read’ event, an article by Gabrielle Cliff Hodges on the benefits of reading aloud to classes reminded me that there was a time when adults gathering together to hear a literary text read aloud was not so unusual: famous nineteenth-century writers like Charles Dickens used to read their novels aloud to groups of fellow adults on a regular basis.

“In a subject studies session in October, one of our lecturers memorably said, ‘I’ve never had a class, in 21 years of teaching, that isn’t settled by being read aloud to – it’s like being a horse whisperer’. I wonder why, when we leave school, we somehow seem to let that magic of hearing a story read aloud together go.

“My immense enjoyment of the Polar Museum event, and these subject studies sessions on the power of reading aloud, gave me the confidence in my first placement to take time reading aloud to classes, and I received positive feedback about classes’ engagement and attentiveness when I did so. In turn, I observed a lesson in which much time was taken up by playing an audiobook of a chapter of Lord of the Flies. I was focusing on picking up on levels of student attentiveness, and it was a marvel to me just how keen a class of teenagers was to follow the story, and how attentively they did listen.

“As teachers of English, part of our job is to help students discover the power of a good story. I hope I will never forget the lessons I have learned about the importance and pleasure of being reading aloud to, and that I will find a way to incorporate this not just into my work in the classroom, but into my life beyond the classroom too. How wonderful that the organisers of the ‘extreme read’ event opened up a space for such a diverse range of adults to remember the power of having a story read aloud to us.”

Rebecca’s thoughts were originally posted on the Cambridge English PGCE Blog.

*Special mention goes to Caroline Hack for alerting us to the phenomenon!