Sometimes we find objects in our store that have little or no known documentation – the object has in effect become ‘lost’. Sometimes, however, museum staff are lucky enough to have an old label or mark on the object. But how can we build an object biography from old labels?

During the autumn term – Michaelmas Term here in Cambridge – I was asked by a lecturer if they could use a mummy net during a practical handling class here in the Keyser Workroom at the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (MAA). Whilst looking through our stores to prepare material for this class, I came across an unnumbered mummy net in a drawer. Without its accession number – its unique, identifying number – it is very difficult to find out anything about it in the Museum’s archives. Luckily, this net had an old collector’s label adhered to the mount. Labels such as these allow us to learn more about the history of MAA’s objects. So, what can we discover about this net from its label?

What is a mummy net?

First things first, what is a mummy net?

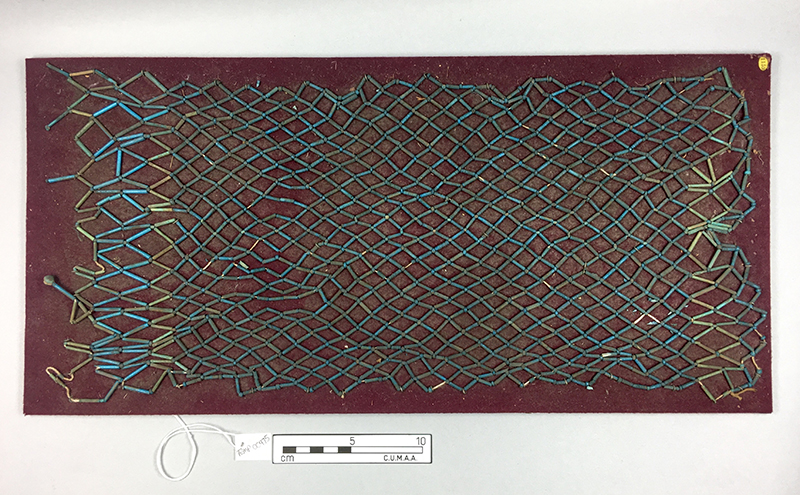

This beaded net was used to cover a mummy’s wrappings before they were placed inside their sarcophagus. MAA have a number of these types of objects in various sizes and states of preservation. Made from beads of faience – a brightly-coloured, quartz-based, glazed material – it acted as decoration but also held great symbolism. The diamond-shaped design was meant to mimic the patterns on everyday clothing, whilst the blue-green colour of the beads was associated with Osiris and rebirth. Small, transportable objects like these nets were sought after items picked up by robbers, antique dealers, tourists and travellers throughout history.

Where do old labels come from?

Objects are sometimes marked or labelled with a wide variety of numbers, letters or symbols – they all mean something, or did, to someone at some point in time. If you work with museum collections on a daily basis you start to recognise these and learn to whom or what these marks belonged. Sometimes these marks are from excavators and usually explain where the object was excavated, what location at the site, or what digging season it was. We have examples of numbers marked on objects by the Museum staff of days gone by that are no longer used or, in some cases, we don’t understand today.

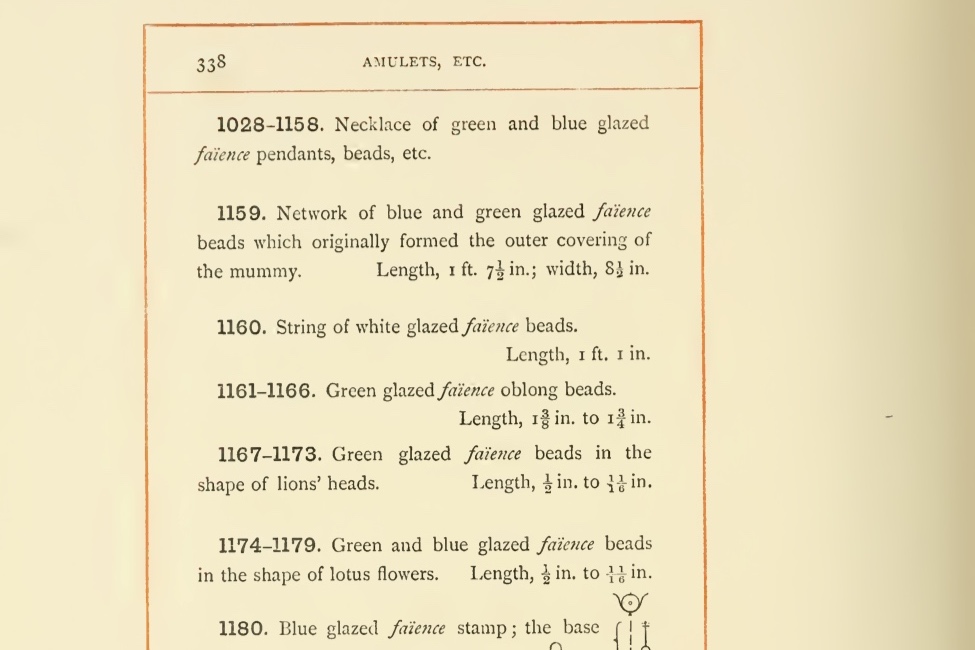

But a huge number of old labels come from previous collectors of the objects, just like the one found on the unmarked mummy net. A number of objects in MAA’s collection can be identified by this very distinctive type of label – a small, yellow, oval sticker with a typed number. From studying the Egyptian collections here, I instantly recognised this label coming from the one and only Lady Valerie Meux.

Who was Lady Valerie Meux?

Valerie Meux is a very interesting character from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Her life seems to be a classic rags to riches tale. It is thought that she met her husband, Sir Henry Meux, whilst working as an actress and banjo-playing barmaid in London. Sir Henry’s incredible wealth came from brewing and his family were not happy about the match. A lavish and flamboyant lady, shunned by high society and never accepted by her husband’s family, she was given to riding around London in a carriage pulled by a pair of zebras. But alongside such outwardly extravagant activities, Lady Meux was a keen collector of ancient Egyptian antiquities amassing a collection of hundreds of items. Her friend, the well-known Egyptologist and Keeper at the British Museum Sir Wallis Budge, created a catalogue of her collection and she had hoped to bequeathed her material to the British Museum. It appears that for some reason the trustees of the British Museum declined her bequest and instead her vast collection was sold on her death in 1911. Her collection was scattered across museums and private collections throughout the world, the location of many of these objects is still not known.

The quest continues!

Because the mummy net still had its yellow Lady Meux label with the number, 1159, clearly marked, I was able to find it in Budge’s catalogue. Adding vital information to the Museum’s database, such as previous owners and bibliographic references, enables me to build up a better understanding of the collections housed at MAA and share this information with the public. Whilst I am pleased that I can build this object’s history the quest has not yet ended! We still do not yet know how this object came to be in MAA’s collections. It appears the Museum did not buy anything directly from the Meux Sale. The objects that were once part of Lady Meux’s collections came to MAA through other collectors, most likely themselves present at the Sale in 1911.

The majority of Lady Meux’s objects came to MAA via the collector John Joseph Acworth and his wife Marion Whiteford Acworth but that doesn’t mean the net also was definitely once part of the Acworth’s collection – that will require more digging. This interesting couple, who collected a large number of Egyptian scarabs and amulets, were chemists and owners of a dry plate company and gifted their vast collection to MAA in the 1940s. Whilst I can’t yet say for certain if the net was ultimately part of this collection gifted by the Acworths, I am happy that I am one step closer to answering the question “where did this object come from?” thanks to the understanding – and stickiness – of old labels.