The exhibition Tū te Whaihanga: A Recognition of Creative Genius opened at dawn on Monday 7th October 2019 at the Tairāwhiti Museum, Gisborne, Aotearoa New Zealand. It featured 37 taonga (Māori ancestral treasures) traded and gifted with James Cook and the crew of the Endeavour and the Tahitian priest-navigator Tupaia during encounters in the Tairāwhiti area in 1769.

Over half of the taonga were from the Sandwich collection, on deposit at the Museum of Archaeology & Anthropology, (MAA) from Trinity College, Cambridge. These included a rain cloak of flax, wood, bone and stone weapons, fishhooks and two decorated paddles. Taonga also came from the British Museum, the Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford, and the Museum of the North, Newcastle.

Eight hoe (paddles) from the different museums were reunited for the first time since they were exchanged when a waka (canoe) came alongside the Endeavour, off Whareongaonga, near Gisborne on 12 October 1769. The voyager’s journals record a flurry of bargaining and gifting over the side of the ship for paddles, weapons and clothing. While initial encounters had been violent, Tupaia’s high status and his ability to act as an interpreter made later meetings more peaceful. Some taonga were probably also gifted to leaders such as Cook, gentleman scientist Joseph Banks and Tupaia, to bind them into local networks and establish reciprocal relationships.

The exhibition opened before the arrival of the Tuia 250 flotilla of Indigenous and European vessels, which commemorated the 250th anniversary of James Cook’s first Pacific voyage. Collaborations with contemporary artists around these events celebrated the continuity and diversity of Indigenous experiences, offering compelling insights into the unequal cross-cultural encounters and their subsequent colonial legacies. Narratives and newly commissioned artworks have remembered the violence and anguish that resulted during the Europeans’ landfalls, such as the deaths of Ngāti Oneone leader Te Maro and the Rongowhakaata chief Te Rakau.

The project to return the taonga has been led in partnership with Tairāwhiti Museum by Hei Kanohi Ora Iwi Governance Group, a multi-iwi group representing the tribes of the Tūranganui-a-Kiwa (Poverty Bay area) and Te Aitanga-a-Hauiti. The exhibition is the result of relationships established between MAA and Māori scholars, artists, curators, iwi (tribe) representatives and other community visitors over many years. Our collaborations were given further impetus through the Royal Academy’s ‘Oceania’ exhibition, which included some of the taonga from MAA; as part of a sponsorship agreement with the New Zealand government, the RA provided funding in support of the Tairāwhiti Museum exhibition

Bringing back this group of taonga after 250 years is the most important moment in the development of the ongoing relationships between the lending museums and Māori communities to date. We hope to continue along this enormously important path and ensure that Tū te Whaihanga is the beginning of a deeper and continuous process that we can build on through further access, collaboration and engagement, foregrounding cultural care and sharing knowledge.

MAA staff working on the loan learnt to adapt to new protocols and furthered their knowledge of tikanga (Māori customary practices and behaviour). For the first time MAA followed tikanga as part of a loan transit. The crates were accompanied by the usual MAA courier but also the Hei Kanohi Ora chairwoman Huia Pihema and her husband Joe, who acted as kaitiaki (guardians). They undertook the correct protocols around the taonga on the long journey, offering karakia (incantations and prayers) to invoke spiritual guidance and protection. These were performed at MAA during the packing of the crates, on departure from the art shipper’s warehouse in London, and on arrival in Auckland, as well as the Tairāwhiti Museum. Karakia also took place at the start of the workshops and exhibition install, and during the exhibition openings.

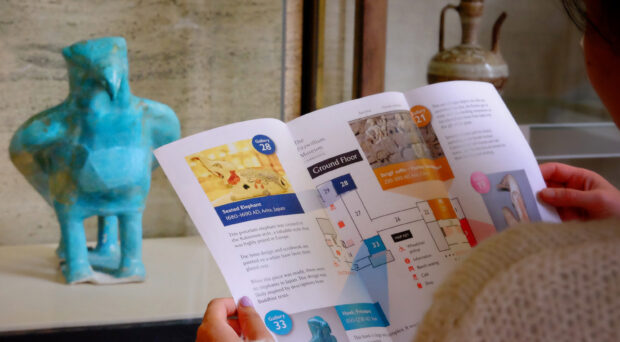

In keeping with Māori protocols, MAA and the other lending institutions needed to be flexible with regards to their standard conditions of loan, while ensuring the safety of the objects. Typically, material travels directly to the borrowing museum’s climate-controlled store where it is allowed to acclimatise slowly after the sub–zero conditions of airplane cargo holds. Then material is installed into waiting display cases, handled only by the MAA courier and conservation teams. However, a key element of the taonga’s return to the Tūranganui-a-Kiwa region was a pōhiri or welcome ceremony, held at the meeting house on Te Poho o Rāwiri marae, belonging to the Ngāti Oneone people. The community was keen to bring the crated taonga directly into the meeting house and have the crates open and the taonga visible. This enabled people to see and reconnect directly with their taonga and prevented the crates looking like ‘coffins’. There were intense emotions of joy and grief during the ceremony as the crate from MAA was opened.

Staff had been concerned that after 250 years in a dry museum store the wood of the taonga would react and potentially crack if exposed to non-climate-controlled environment. It had been agreed that crates would be opened but that layers of insulating foam around the material would remain and the taonga would remain crated. However, an on-the –spot request to remove the hoe (paddles) from the crates was agreed to by the couriers and the hoe were carefully paraded around the meeting house, with people reaching out to touch them. This acquiescence meant people were able to re-engage with their taonga in their home environment, which had not been possible since they were collected 250 years ago. Three days of workshop/wānanga sessions continued this unprecedented access to the returning taonga. The verb wānanga means ‘engaging in a process of sharing and reflecting upon current understandings that leads to decision-making for future success and the creation of new knowledge’. Weavers, carvers and artists and staff from Tairāwhiti Museum and the lenders shared their knowledge about the taonga during these wānanga.

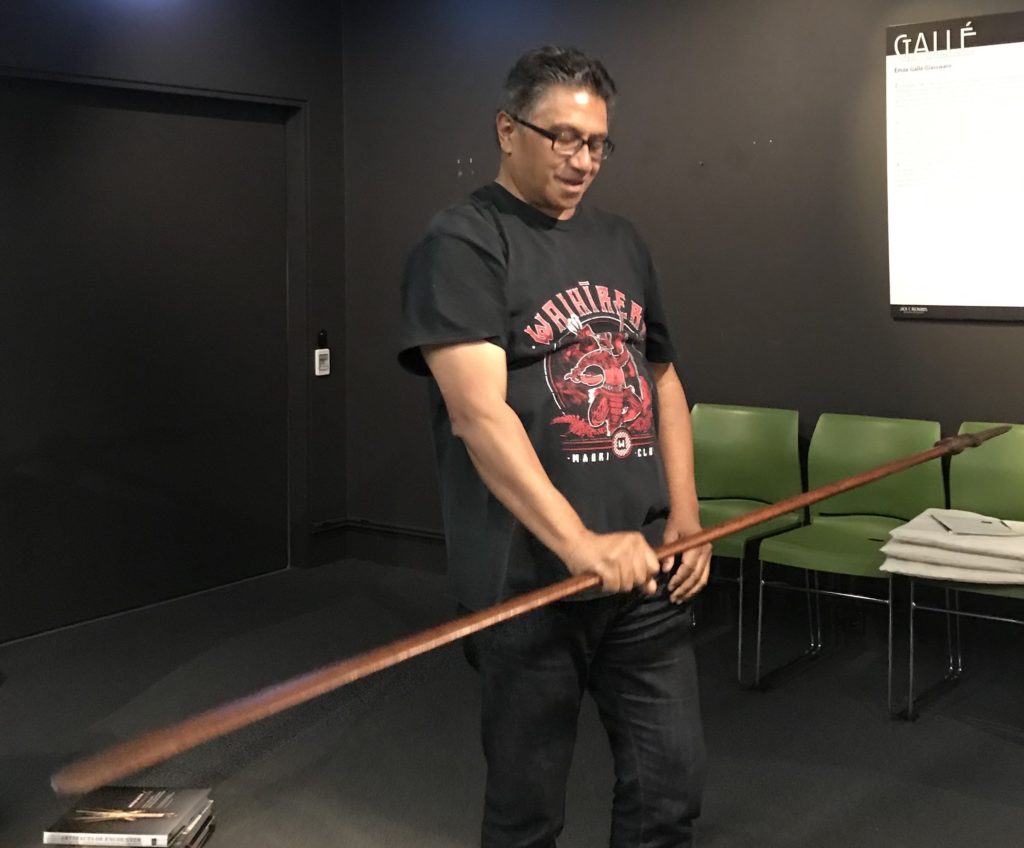

These sessions bought together experienced artists, practitioners and knowledge holders as well younger people and those new to historic taonga. Weapons came to life as they were swung, balanced and gesticulated with, while weavers counted rows of warp and weft threads with their fingers and sought to understand the weaver’s intentions. Experienced stone and wood workers were able to distinguish tool manufacturing marks from use wear or impact. Julie Noanoa, Tairāwhiti Museum’s education team leader, “felt a special connection” to the small wooden kōauau (flute). As she played it, haunting sounds emerged, drawing people close.

Musical instruments are rarely played once they enter a museum and their enforced silence isolates them from their original function MAA’s long standing protocol of facilitating community access through direct physical contact with the material we care for, was warmly welcomed and exclaimed. This deviates from the usual museum practice of wearing gloves to shield objects from finger marks and protect the wearer from historic pesticides. We are open to tactile and investigative handling of material and recognise that many Indigenous people, including the Māori, see museum collections as living beings, more than just objects. This emotive tactile connection is essential. Despite this (and nearly 20 years of working with similar collections) it is still professionally terrifying to see weapons slashed and ‘helicoptered’ around the head, as if in battle. The urge to step forward, exclaim ‘be careful’ and urge ‘proper’ handling protocols was hard to break.

However, what is ‘proper’? The freedom to engage with historic taonga, the knowledge shared and gained, and the expression of emotions attached to taonga were an essential and overwhelmingly positive element of the wānanga. The Māori equivalent to my role as Collections Manager, where I am responsible for the care of the object collections, is ‘Kaitieki Māori (custodian of taonga Maori)’. This relates to concepts of guardianship which resonates strongly with my work in the Museum. It strengthens my long-held beliefs that we are guardians and not gatekeepers of taonga from around the world. Seeing first-hand the emotions invoked by the taonga hits you hard in the chest and is a far cry from understanding it as a concept. I intend to use these lessons about standing back and listening harder, and embrace the role as a Kaitieki in the future.

While the return of the taonga has been widely celebrated, they have also created division and disagreement. The ownership of taonga, the genealogical origin of carving styles and circumstances around their acquisition continues to be intensely debated. Polynesian Navigator Tupaia remains a key figure in the 250th commemoration, bringing together shared Polynesian histories of ocean migration and skilled navigation. He is popularly seen by many Māori as the recipient of most of the taonga collected on the voyage, though there is limited written evidence for any individual collectors. Further work remains to combine oral histories, voyage accounts and carving styles to establish if taonga can be connected to specific exchanges or iwi. However, the return of the taonga with the correct tikanga and the productive wānanga sessions, marks the start of forging new ways to listen and learn on both sides. These will shape new ways of working with collections and their descendants.

Images of taonga and videos from the wānanga including the playing of the musical instruments are available at https://tairawhitimuseum.org.nz/exhibition/tu-te-whaihanga-online-exhibition/

The Covid-19 outbreak saw the exhibition closed temporarily but we hope the show will be extended past the planned closure of October 2020.

A basic searchable online catalogue of MAA’ collections can be found at: collections.maa.cam.ac.uk