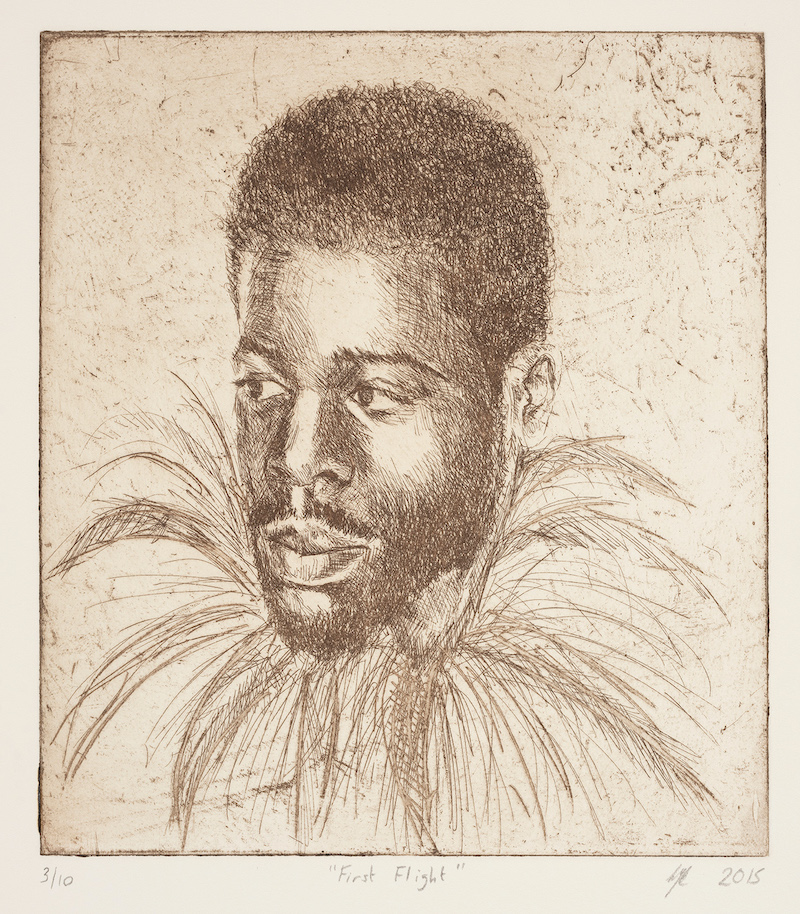

The sepia tone of the printing ink used in First Flight, a set of ten etchings of male heads (recently acquired with the invaluable help of The Friends of the Fitzwilliam), brings to mind the rich warmth of an old master drawing or an old photograph. Disparate references and associations are common in Yiadom-Boakye’s work and such diversity – created in the eye of the spectator – is something that she readily invites.

Yiadom-Boakye is best known for her large, figurative oil canvases and currently has a show dedicated to them at Tate Britain (Lynette Yiadom-Boakye Fly In League With The Night, until 31 May, 2021). The striking, often enigmatic Black figures which populate these works are not portraits but rather composites of a range of material: memories, imaginings and more tangible found imagery including photographs and the work of other artists across art history. Sickert, Manet, Degas and Sargent are names most frequently cited as influences and Yiadom-Boakye’s early grounding in the European portrait tradition – learning about “how a face sits” – was key to her later divergence from it.

The embrace of history and tradition and the remaking of it is a major theme of Yiadom-Boakye’s work and this is evident both in her figurative approach and choice of technique. Her commitment to oil paint is equalled by her preference for the historical intaglio technique of etching over technologically-enhanced printmaking processes like polymer photogravure or giclee which are currently popular among contemporary artists. Yiadom-Boakye’s addition of the pre-fix ‘hard ground’ in written descriptions of her etchings is unusual. The ‘hard ground’ or wax resist used in etching isn’t normally mentioned when describing the technique. Nevertheless, this apparent restyling of the term speaks to the conversations that exist in her work between the art of the past and the concerns of today.

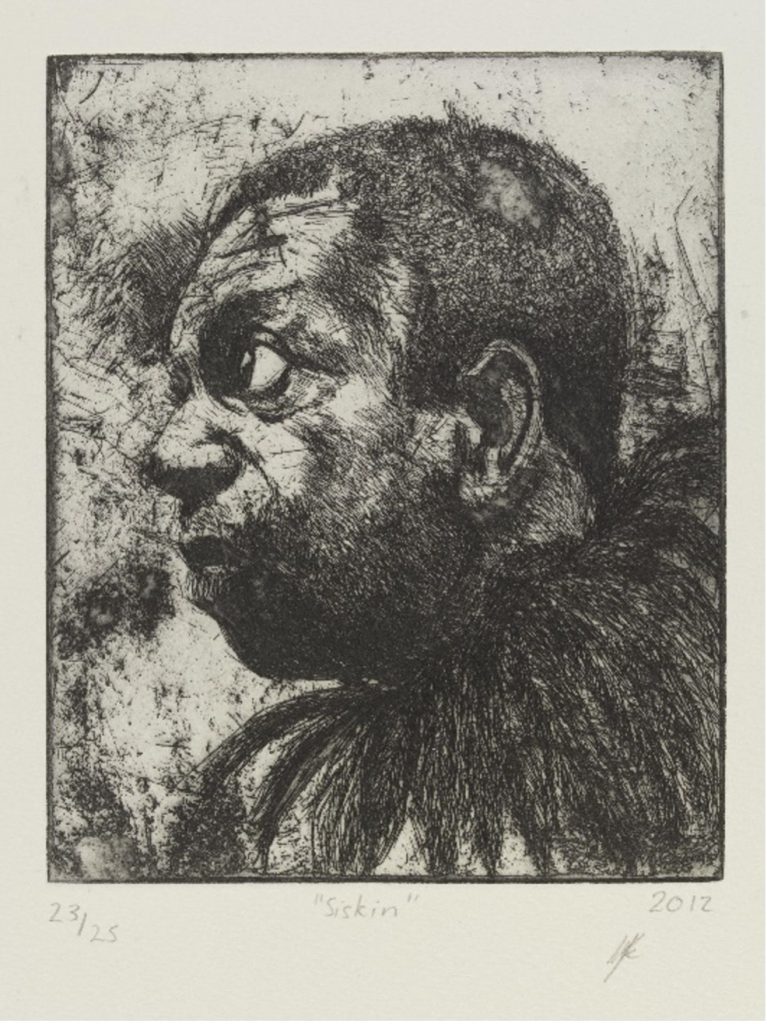

For Yiadom-Boakye, who does not make preparatory drawings for her paintings, etching is an opportunity for her to draw and to work at a much slower pace. Whereas canvases are created largely in one session, etched plates demand successive processes of editing and proofing. Yiadom-Boakye has been producing prints since 2012, the date of her first etching, Siskin, which is one of a number of prints and canvases relating to a group of works on the theme of Black men and birds.

This way of working in groupings and series has enabled her, on a practical level, to speed up the printmaking process. Speaking in interview in 2015 about her experience of etching during the making of First Flight, she explained: ‘It’s slower but I got round that by working in a series. Some were discarded, but it was about producing several of something and editing some out.’ The role of groups and series and ideas of editing and re-making are also crucial to a wider purpose that relates to questions of identity and representation. Yiadom-Boakye’s invented, fictitious Black bodies are multiplied through an inbuilt process of repetition of characters and motifs which projects a concept that she has described variously as ‘infinitude’ or ‘endless possibility’, stating: ‘Blackness has never been other to me. Therefore, I’ve never felt the need to explain its presence in the work anymore than I’ve felt the need to explain my presence in the world, however often I’m asked. … [T]he idea of infinity, of a life and a world of infinite possibilities, where anything is possible for you, unconstrained by the nightmare fantasies of others, to have the presence of mind to walk as wildly as you will, that’s what I think about most, that is the direction I’ve always wanted to move in.’

Yiadom-Boakye’s printmaking lies at the heart of this project. All of her etchings produced since 2012 have featured the recurring motif of Black male heads – of varying ages – wearing ruffs or collars of feathers. The series, begun in her paintings of 2009 with Bird of Reason and titles referencing real bird names, including Wren, Skylark and Greenfinch, continued with the etching Siskin and Fly, a set of twenty etched male heads wearing feather collars. First Flight of 2015 was followed by Blackcap of the same year and more recently Red Kite (for Parkett no. 99) (2016) and Paridae (2018).

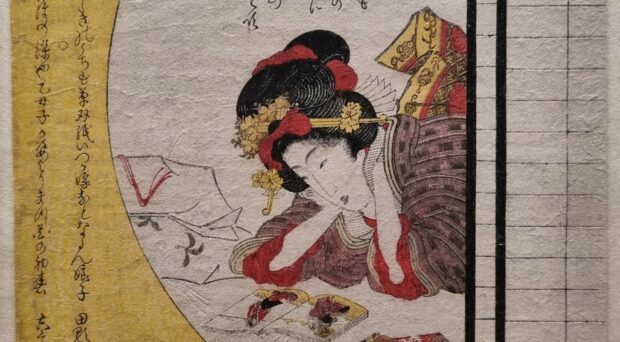

For Yiadom-Boakye, titles represent an extra mark that is built into a work and not an explanation. She invites viewers to create their own narratives about her characters and in this way resists definitive meanings, relishing ambiguity and multiplicity and reserving space for the unsaid. The combination of multiple Black male heads wearing feather collars presents us with an abundance of association. Yiadom-Boakye’s feather collars as allusions to the fashionable lace ruffs of seventeenth century Dutch and Flemish portraits has been cited as a way in which she disrupts the connections to (white, Western) power and status perpetuated by that tradition. The series of half-length portrait prints depicting famous nobles, scholars, and artists conceived by Anthony Van Dyck according to his own etched designs and known widely as the Iconography offers up points for comparison and divergence with Yiadom-Boakye’s groups of invented collared heads. In the rare, early states of the Iconography prints, those etched by Van Dyck himself before details of costume, setting or the names of the sitters were added by professional engravers, often only the priority area of the head with collar below have been sketched out.

Yiadom-Boakye’s series of disembodied etched heads both assert and disavow such hierarchical processes of making. She has referred to her role as artist in terms of ‘playing God’ stating that: ‘The reason I didn’t want to work from life was because I wanted that open-ended freedom to do whatever I wanted with them. As soon as I related them to people who existed, then it felt like the person I was painting had to be honoured, whereas working the way I do, there can be flushes of fantasy.”

Yiadom-Boakye’s etchings certainly seem particularly pertinent at a time when across the University of Cambridge Museums we are investigating the legacies of enslavement in our collections. These investigations are perhaps leading us to re-evaluate the implications of a collar in terms of subjugation and punishment and to re-examine how colonial discourse has engendered restrictive and exclusive viewpoints. Yiadom-Boakye subverts the suggestion of such prejudice and negativity in subtle ways. The feathered collar might reference the trope of the exoticised Black figure draped in animal skins or tribal emblem, but may also be merely a theatrical prop, an accessory to role play – the liberating ‘flushes of fantasy’ she speaks of.

In First Flight, the ten invented heads vary in pose and expression, many apparently captured in the process of speaking, or singing, frowning and smiling. The uninhibited human emotion on display ranges from elation and bemusement to tiredness and contentment. Responses to Yiadom-Boakye’s work have inevitably drawn comparison with the seventeenth-century Dutch concept of the non-portrait ‘character head’ or ‘tronie’. Many of these imaginary portraits engage in costumed role-play and display exaggerated facial expressions. The open mouths, wide eyes and furrowed brows of the male heads of First Flight recall Rembrandt’s tronies, especially the portraits he made of himself in different guises.

Such a legacy seems also to consciously extend to the formal qualities of Yiadom-Boakye’s plates. Their physical impact encompasses a variety of mark-making: scribbles (hair), hatching and cross-hatching, delicate, spidery lines (feathers), areas of intense chiaroscuro and irregular levels of surface tone. Lines and marks add character to the backgrounds of her heads and vary from plate to plate but indicate nothing of contextualisation of time or place.

Yiadom-Boakye has spoken of this timeless quality in her work as a route to freedom: ‘For me there’s the wider exercise of removing time or trying to, in some ways, disregard it. I suppose it goes to also thinking about the figures themselves and what they represent and what they stand for; and what a history is and what a future could be.’ First Flight participates in Yiadom-Boakye’s repetitive sequence of bird imagery and its associations with fantasy and independence. The shifting variety of this artist’s collared heads reminds us of the breadth of possibility for the human in the modern world outside of any restrictive notions of otherness.

A selection from Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s “First Flight” will feature in a new case display at the Fitzwilliam Museum alongside figurative etchings by Anthony van Dyck and Rembrandt van Rijn.

Turning Heads: Lynette Yiadom-Boakye – Rembrandt van Rijn – Anthony van Dyck

17 August 2021 – 20 February 2022

Fitzwilliam Museum, Gallery 15