What if a storage container could tell you when a museum object needed treatment? Why are so many toys sacrificed in the name of conservation? Should we clean plastics like we clean paintings? Is sustainable cold storage a pipe dream? How can we get the most from collections that are doomed from the start?

These questions and many others were addressed at the conference ‘Plastics in Peril: conservation of polymers in cultural heritage’, jointly organised by the University of Cambridge Museums and the Leibniz Research Museums in Germany, particularly the Deutsches Museum in Munich, the Deutsches Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin and the Deutsches Bergbau-Museum in Bochum. The conference was a lively event, held online in November 2020, with attendees from every continent in the world except Antarctica:

Thanks to generous funding from the Aktionsplan Leibniz Research Museums, the conference was free to attend. The good news is that if you missed it or want to watch again, 25 of the talks are now available to watch on the University of Cambridge Museums YouTube Channel.

Plastics are often inherently unstable, but are a key element in our cultural heritage from the last 100 years. They challenge conservators, conservation scientists and collections managers to throw out old assumptions and develop new ways to manage and preserve them. The ‘Plastics in Peril’ conference highlighted many practical strategies that museums can use right now, as well as showing some exciting cutting-edge research into new treatments. These included Smart storage systems, using supercritical CO2 for cleaning and consolidating foams, and making close-to-invisible repairs on polished clear plastics. An important theme was understanding the surface energy and chemistry of plastics and using this to optimize treatments, and several groups reported successes using this approach.

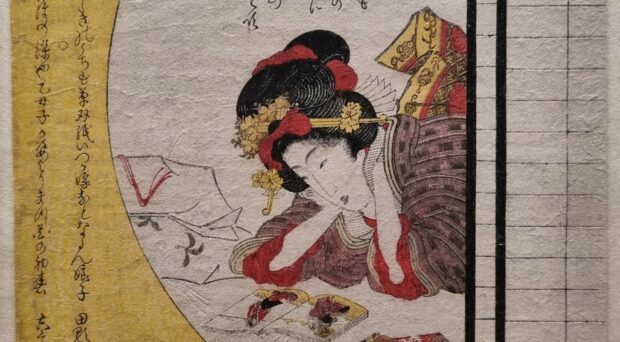

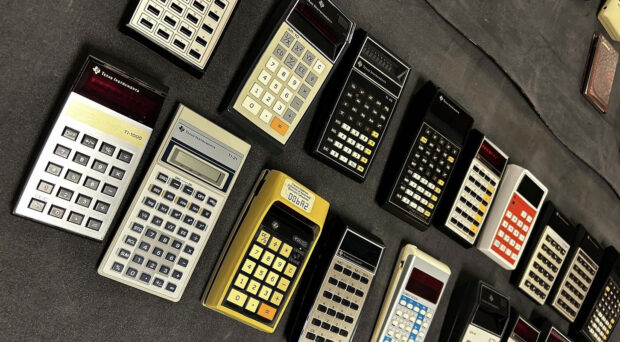

Throughout the meeting we saw some extraordinary objects and artworks made from plastic which are now in museums worldwide – from a masterpiece of 1930’s Constructivist art by Moholy-Nagy and the 2003-onwards ‘Black Factory Archive’ by Pope-L, to the ingenious and playful lei made by Samoan people in New Zealand. The scale of some pieces is challenging and awe-inspiring – like the ‘Aeromodeller’ airship by Belgian Artist Panamarenko, which fills a huge hall, or the Keith Haring murals which cover whole buildings. Other objects reminded us how plastics are part of everyday life, like the football boots of Pele and George Best, or the very cute prototype robots ‘Hinz’ and ‘Kunz’ from the 1960’s:

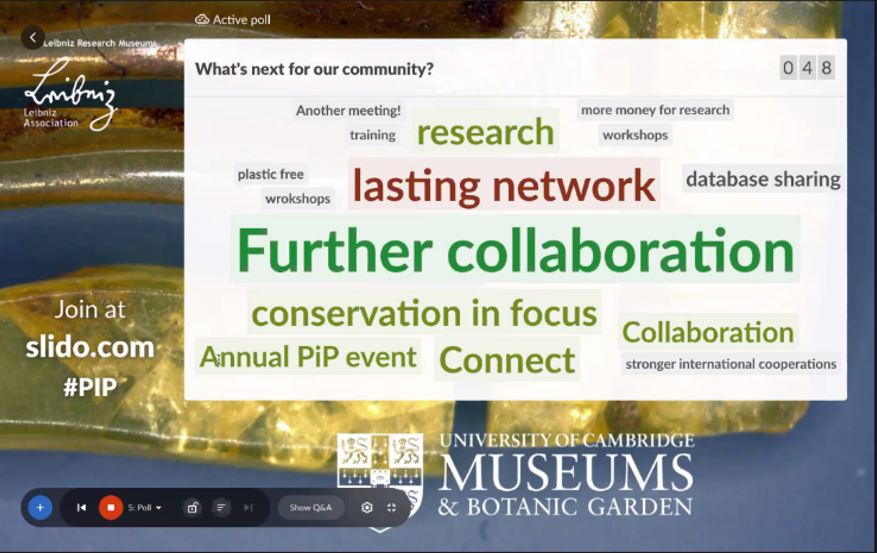

The role of conservation science in understanding degradation and developing conservation treatments was a recurring theme, and particularly the value of conservators and scientists working side-by-side on specific projects. Sharing knowledge more widely across the conservation community and across disciplines was also strongly supported by the conference attendees, as a poll at the close of the meeting showed:

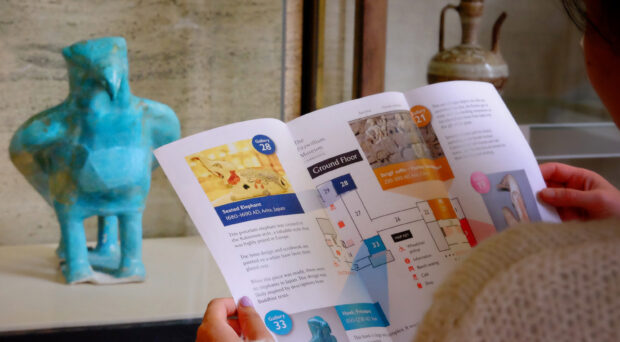

Not all museums have conservation scientists and many have very small budgets, but there were inspiring examples of what can be achieved by using locally available technology – especially if, like Auckland Museum, you have a resident engineering genius called Ged! Likewise, many museums don’t have access to expensive technology for the crucial first step of identifying problem plastics, but the Plastics Identification Tool developed in the Netherlands can help to overcome this.

Thinking about plastics in museums can be uncomfortable. It is certain that many objects will self-destruct and we cannot save them, and this can be hard for conservators and curators to accept. In the wider world our relationship with plastics is complicated. They are fundamental to so many medical, industrial and domestic products that we have come to depend on, and yet they also cause appalling pollution in our environment. In the museum sector we must learn to accept loss, ‘curate decay’ and put our resources where they will have the best effect, based on what we know of our collections. Whether you see plastics as a blessing or a curse – or a bit of both – this conference reminded us that for museums to tell the story of plastics in our world and solve the problems it presents, we must work together, form new partnerships and be prepared to rewrite the rules.

25 Plastics in Peril talks are now available on YouTube, and the book of abstracts is here. A publication with selected peer-reviewed papers from the meeting will be published online in the University of Cambridge academic repository ‘Apollo’, later this year.