In early 2020, a group of young children and staff from a local community playgroup spent four mornings ‘in residence’ at the Fitzwilliam Museum. This collaborative action research project built on the findings of the 2017 UCM Nursery in Residence aiming to explore young children’s encounters with objects, spaces and places.

Educators from the museum and the playgroup worked together to plan, deliver, and document what happened when 10 young children visited the museum. The project enabled us to develop approaches to people-centred research, supported professional learning, and encouraged community participation.

Our Early Years programme aims to bring the benefits of museum visiting to as wide a range of people as possible. With this in mind, we chose as research partners, a playgroup that is situated in an area of the city currently under-represented amongst museum visitors. Playgroup staff selected a group of 10 children to take part, and we sought consent from parents and carers for their children to participate in the research. We had planned that the group would visit the museum five times in the spring of 2021 but this was revised to four visits due to the closure of the museum during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The group took part in a variety of different collaborative activities when they visited the museum: exploring the galleries and museum building and making artwork in the public spaces and in the art studio. Their experiences were recorded using video and photographs and through field notes and reflective journals compiled by the playgroup and museum staff. Participating staff and families filled in a pre and post project questionnaire and the Head Teacher was interviewed six months after the project took place. This provided us with a wide variety of rich information to analyse, and enabled us to consider individual moments and themes from many different perspectives as we assessed our data and reflected on our findings.

The project was designed collaboratively by a project advisory group consisting of staff from the playgroup, the Faculty of Education and practitioners from the previous residency project. However, limited time and resources meant that the museum-based practitioner researchers carried out the data analysis and wrote up the project findings.

What did we learn about developing a sense of ownership and belonging in shared cultural spaces?

One of the key themes identified through the analysis was children’s interest in leaving and exploring physical, verbal and graphic traces over the course of the residency. Recording these traces over the course of their different visits helped them to develop a sense of ownership and belonging and to communicate their own sense of place. This led us to consider how museums might provide opportunities for children to not just enter into museums spaces but to participate in a dialogue with them. Creative and open-ended opportunities for young children to explore and experience the museum enabled them to communicate and negotiate ownership and familiarity as autonomous, complex individuals rather than simply component parts of a family or group. Through these they began to develop their own sense of agency and identity.

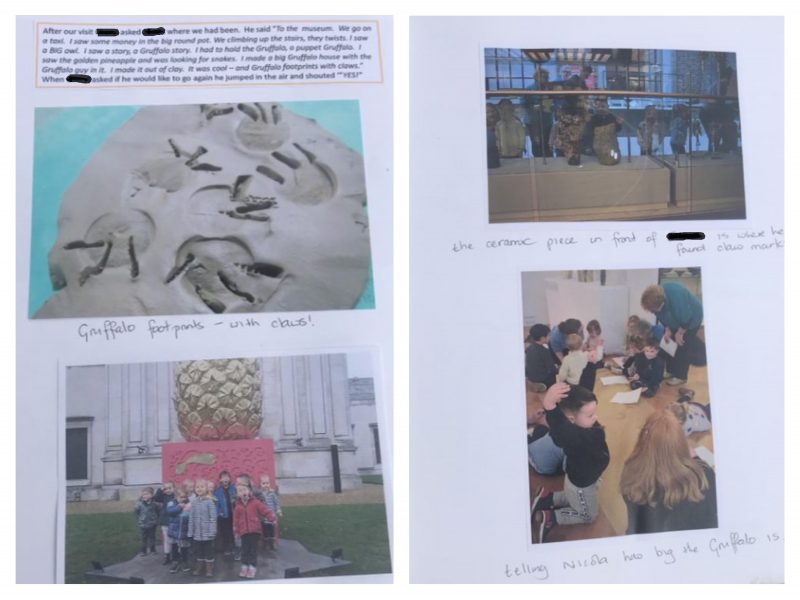

An example of this was the children’s responses to Ceramic Vessel by Sara Radstone. On the first visit to the museum we read the picture book The Gruffalo by Julia Donaldson and Axel Scheffler together. On the way through the galleries, a child noticed Radstone’s pot, and excitedly told the group that he had found Gruffalo claw marks. On each subsequent visit, the group, usually led by the same child, would pause at this object to look for the Gruffalo prints and scratches. On analyzing the data, we found that footprints, trails, and claw marks, in particular those of the Gruffalo, featured regularly in his sketchbook alongside a photograph of his clay model of the Gruffalo claw marks and a photograph of him and the group looking at Ceramic Vessel.

The playgroup staff recorded his description of this visit:

‘I saw a story, a Gruffalo story. I had to hold the Gruffalo, a puppet Gruffalo. I saw the golden pineapple and was looking for snakes. I made a big Gruffalo house with the Gruffalo guy in it. I make it out of clay. It was cool- and Gruffalo footprints and claws.’

This shows how he connected his own and other’s mark making to bring together visual and narrative elements from a familiar story, a museum object and his own interpretation and response. The excitement at his discovery contributed to his growing sense of ownership and belonging within the museum. On subsequent visits, he introduced new adults who joined the group to the “Gruffalo Pot” as we walked through the galleries, generously extending an invitation to participate in and share his museum experience. He said to one of them, ‘I love the Gruffalo claws…I could show him the Gruffalo claws. I know a way! I’ll go first!’ The children rushed to arrive at the case before the visitor and then pointed out the ceramic vessel. This example demonstrates how marks and traces made by others and through art making can help young children to negotiate their sense of ownership and belonging within the museum. The artwork functions as a liminal space, a bridge between the curated and accepted museum narrative and the imagined and still-becoming world of the children’s experience. They proudly share the pot and the marks it contains as a way of introducing newcomers to their group’s museum experience, re-created and transformed through their own understandings, interests and story making.

What did we learn about the potential of collaborative action research in the university museum?

The collaborative nature of the research provided us with opportunities to return to the data to interrogate difficult moments together and to challenge our different perspectives. The visual data collected through photographs and films were particularly useful for comparing and analyzing children’s responses alongside adult interpretations. These multiple sources of data helped us understand how and why we viewed the same events differently and encouraged us to attend to different ways of being and knowing within the museum.

Another exciting outcome of the research was that as practitioner researchers, we were able to feed our findings directly into museum programming. Feedback from the playgroup team revealed frustration at the display and interpretation of a hoard of coins which had been discovered locally. The group had been particularly interested in the coins on display in the museum and had worked with Adi Popescu, the Museum’s Keeper of Coins and Medals, on their last visit. As a result of the research project we then worked collaboratively to move the hoard to a more prominent position in the museum and design and write new interpretation labels depicting the site of the find and bringing in the voices and perspectives of the research participants.

What did we learn about the challenge of collaborative action research in the university museum?

We found that the status of the museum and university was a double-edged sword having both positive and negative implications. Where some of our partners described feeling empowered by the project, in part because of the prestige associated with the university, one of the practitioners continued to feel that the museum was not a place where they belonged. This led us to reflect on the importance of allowing space for disagreement and conflicting views within collaborative research. The decision not to participate or be inducted into the dominant museum narrative was acknowledged as a potent statement in its own right.

This research project enabled us to explore the potential of people-focused, participatory research within the university museum. If we are genuinely committed to exploring the potential of collaborative research in museums we must work hard to develop partnerships with individuals and communities who have previously been excluded from academic research. By focusing on young children and their experiences in the museum we can develop our understanding of how museum buildings, objects and spaces can function as dynamic and exciting places where even our youngest visitors have opportunities to experience, to participate and be heard. We are exploring further projects and collaborations in these areas and are excited by the potential of this work.

We continued have continued to work with the playgroup since the research project ended and were invited to a very special private view of children’s artwork at the end of the lockdown. You can read more about what happened next in Nicola’s blog here. This blog is adapted from two papers sharing the findings of the research:

Noble, K. and Wallis, N. (2021), “It’s our museum too: co-producing research in a university museum through a nursery residency programme”, Qualitative Research Journal, Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. https://doi-org.ezp.lib.cam.ac.uk/10.1108/QRJ-01-2021-0009

Wallis, N. and Noble, K. (forthcoming) Leave only footprints: how children communicate a sense of ownership and belonging in an art gallery, European Early Childhood Education Research Journal

Or contact Kate and Nicola to find out more.

This research project was funded by the Cambridge Humanities Research Grant Scheme (2019-2020). We would like to thank the late Dr David Whitebread, Dr Ros McLellan, Dr Jo Vine, Gemma Spence, Susan Lister & Margaret Winchcomb for their expertise and guidance as part of our Project Advisory Group. We also thank the Fitzwilliam Museum, especially Education Assistants Alison Ayres and Nathan Huxtable, Keeper of Coins and Medals Adi Popescu, Head of Learning Miranda Stearn, and the staff, children and families of Playlanders playgroup for their support and participation. The project was also runner-up in the 2021 Vice-Chancellor’s Awards for Research Impact and Engagement at the University of Cambridge.