What if broken things were not to be mourned, but to be celebrated? The Stores Move project at the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology has recently completed its work on the West, North and East African collections and uncovered some amazing examples of repairs. Discover how damage can trigger extraordinary displays of skills and strength.

In the last few months, the Stores Move team has explored ethnographic collections from Africa at the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (MAA), coming across many objects that had been broken and repaired in their countries of origin. While our first reaction is always to lament the damage (we are museum practitioners after all!), it is never long before a murmur of wonder grows, and members of the team assemble to gaze at the skilful ways in which cracks, tears and splits have been repaired. These objects clearly mattered to people, and a great deal of thought, care, skill and creativity can be seen when looking at the delicate fibre or leather scars they bear today.

Mending presents risks. Damaged objects are vulnerable. Drilling holes near a crack, weaving material through, applying pressure and creating tension could cause the fracture to worsen. It takes skill, and a deep understanding of the materials to produce a successful repair. It also takes artistry to create one so intricate that it sometimes overshadows the object it adorns.

There are many reasons why wounded objects are worth repairing. Some objects may be heirlooms, or valuable because their permanent loss would disrupt daily life. Others may have spiritual or religious purposes that can no longer be fulfilled if the object is not mended in an appropriate way. In some cases, artefacts can be difficult to make, or the materials difficult to acquire, justifying the time and effort invested in repairing them.

We don’t know much about the shields of buffalo or rhinoceros hide found in the stores, folded in two. They are large, thick and heavy, taking on the properties of the animal they were made from. They are tough and, despite repeated blows, would have continued to protect most of the wearer’s body. Many shields from Uganda show evidence of battle wounds probably caused by arrows and spears. While these objects were undeniably damaged, their repairs made them more powerful. The slits and cuts were sewn up with thick leather cords, creating visible scars – hurt but healed, and stronger than ever. A defiant message conveyed to the enemy on a battlefield.

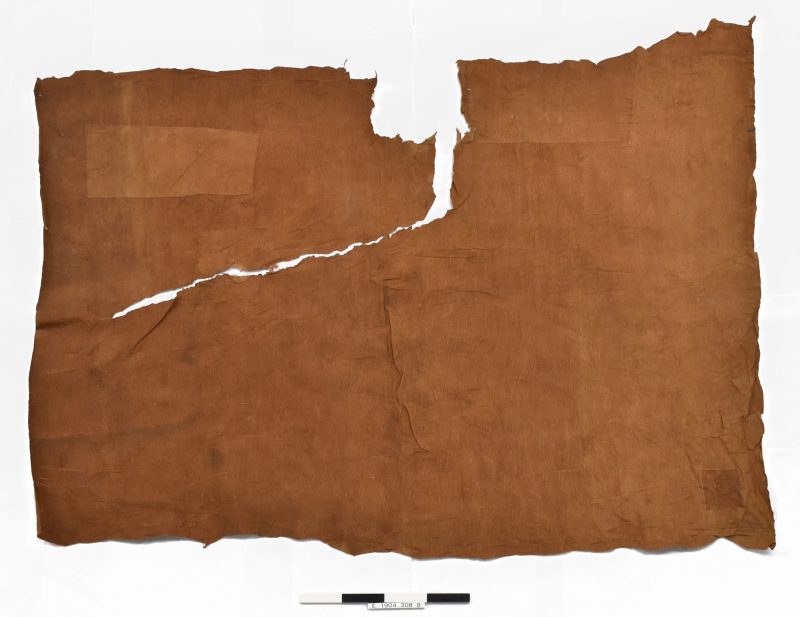

Repairs are sometimes an integral part of the making process too. In Uganda, large barkcloths were made by beating the inner bark of the mutuba tree (Ficus natalensis). Once beaten to the desired thickness, the cloth was assessed to pre-empt damage. Small creases were stitched up to even out the surface, and rectangles cut out around weak areas and replaced with rectangles from a different cloth, sewn with plantain fibre. The fineness of the stitching makes the patches almost invisible to the eye on the front, but the back shows a network of raised scars, precise, and tight. Like a roadmap of accidents avoided.

There is something magical about repairs. How was the large gourd (above) repaired when the top aperture is no larger than 2cm diameter and affords no access to the inside? With a repair whirling around half of the object’s surface, how were the angles and areas of overlap mapped out in such a way that the stitching unfolds as an almost uninterrupted, interconnected line?

Repaired objects have a real transformative power on people who come in contact with them. The mind is made to forget about the damage, and drawn to the solution, the stitched ladders, swirls and braids. They alter the object’s balance and dimensionality, create new dynamics, angles, textures. They impact the way we approach objects, handle them, document them, photograph them, pack them. Somehow, repaired objects push us to connect to them on a more intimate level than less vulnerable objects in the collections. They mark us, even when the details of their physical journeys are unknown to us.

There is much to be learnt and admired about broken things and the way they are ‘fixed’ to lengthen their life journeys and continue to enhance people’s lives. Next time you find yourself in a gallery, take a few minutes to lean in, and look for the cracks, tears, or scars. Broken things have many stories to tell.

To discover more repaired objects from MAA’s collections, head to the collections’ portal https://collections.maa.cam.ac.uk/objects/

Search for ‘contemporary repair’ and narrow your search to ‘Anthropology’.