Kirsty Kernohan, a Photographic Collections Assistant at the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (MAA), discusses the journey of the Poignant transparencies; part of an extraordinary collection of photographs bequeathed to the Museum by anthropologist Roslyn Poignant and her photographer husband Axel.

Making a start

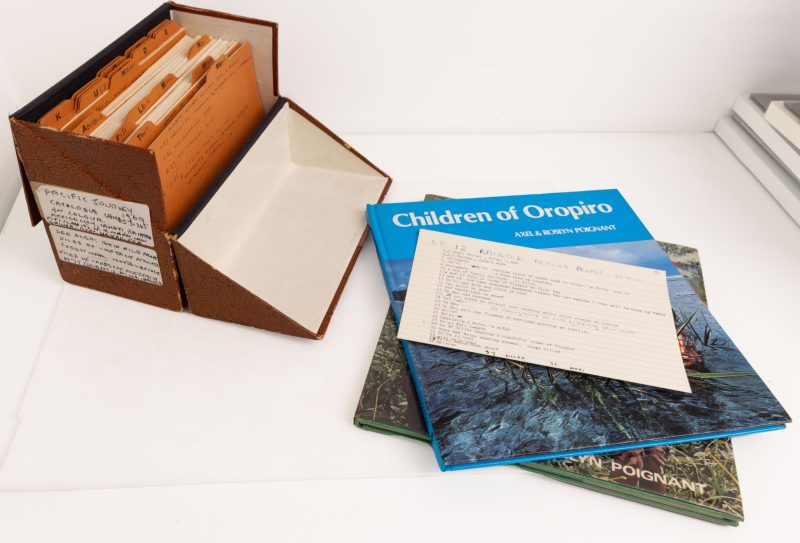

When the collection arrived, the first step was to make an inventory of how many and what kind of photographs were in the collection. This allowed us to approach the task of cataloguing and digitising all 18,000, which range from large exhibition prints to tiny negatives. We decided to start with the 35mm colour transparencies, almost 5000 of them, because they had the most complete written notes.

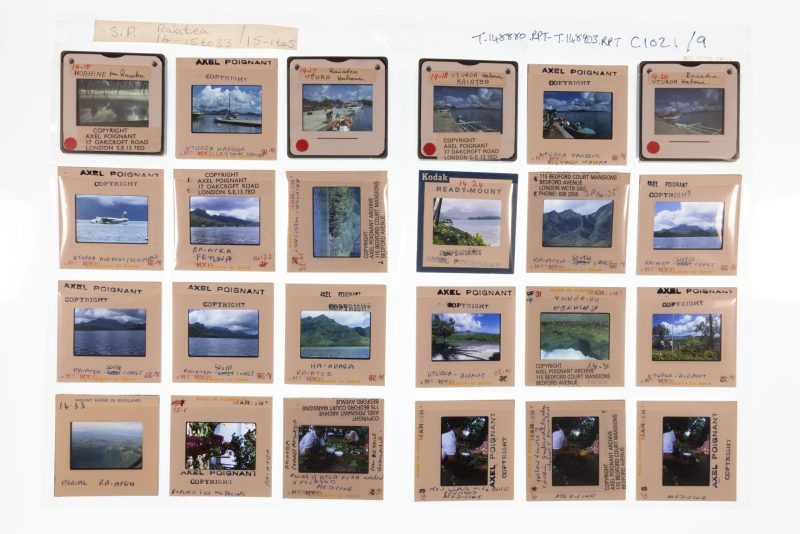

The team soon discovered that most of these transparencies told the story of a research trip around the Pacific in 1969 and were accompanied by typed notes on catalogue cards which Roslyn Poignant labelled ‘Pacific Journey 1969.’ Through just some of these photographs, this blog will follow the Poignants on their journey; and at the same time, follow the transparencies on their own journey through MAA, as they are stored, digitised, catalogued, and used.

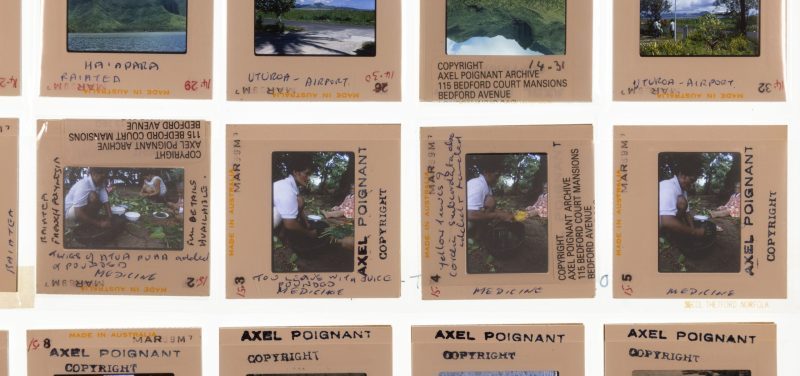

The transparencies arrived in archival sheets, ordered and numbered by the Poignants. Looking at the transparencies laid out in their sheets allows us to easily see sequences across several images. The Poignants’ photographs often illustrate the steps of different skilled practices, such as the sequence above. These photographs show Enriette, a Raiatean woman, making medicine by crushing leaves and berries; looking at them as a sequence gives a sense of her skilled movements.

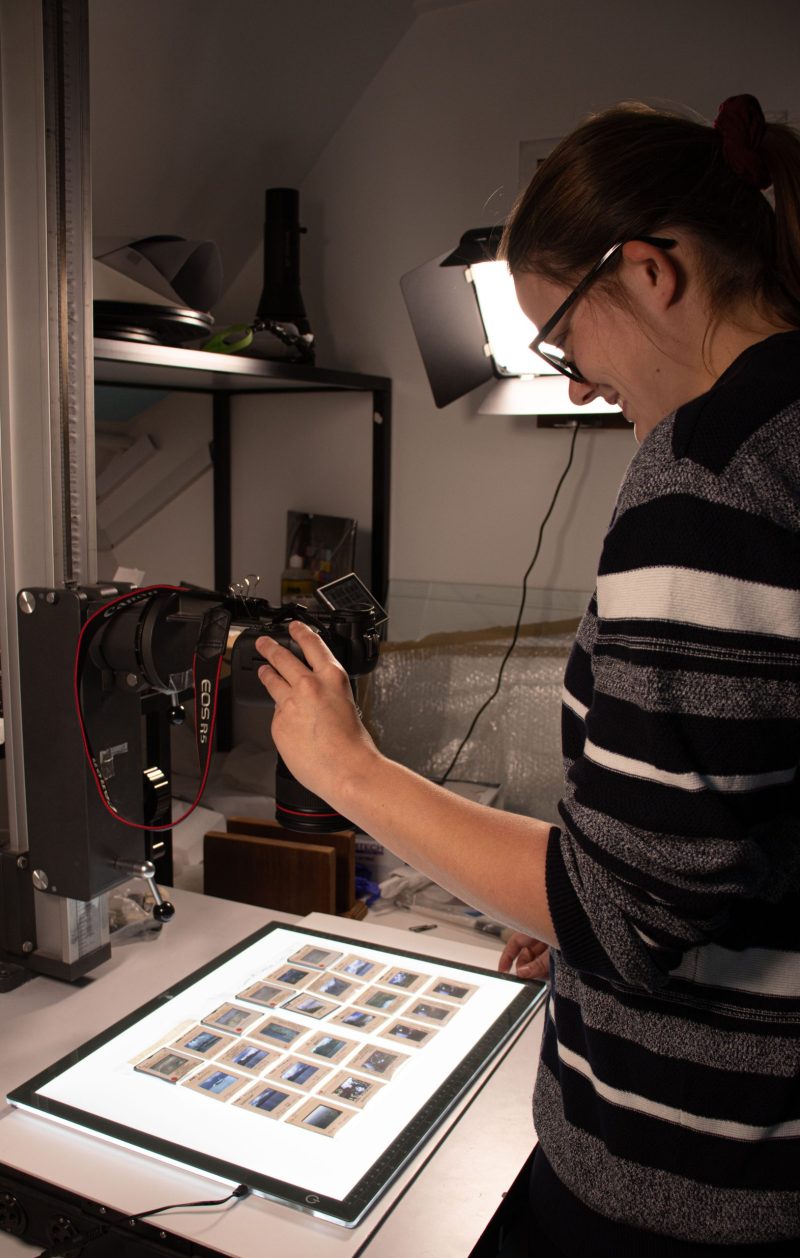

Getting digital

Once the transparencies are safely stored, the next step is to digitise them by taking images using a mounted camera above a light box. Although the transparencies are very small, the high-resolution digitised images show the incredible amount of detail and vibrant colours in the Poignants’ photographs. We lightly edit the digital images to make sure that they are bright and clear enough to see these details.

In addition to being beautiful, the photographs also tell us a lot about the Poignants’ work. This photograph was made in Whakarewarewa, a village in the North Island of Aotearoa New Zealand. It is another example of the Poignants’ interest in skilled practices, showing a Māori artist sitting beside a pile of harakeke (New Zealand Flax) which she is preparing to make into piupiu (skirts), like the ones on the fence behind her.

As well as documenting the skill of Māori artists, the details in this photograph tell us about how the Poignants gathered knowledge as they made photographs. If you look closely at the bottom of the photograph you can see the shadow of Axel Poignant holding the camera, reminding us that photographs are made by both those behind and in front of the camera in relationship to one another.

The women leaning against the fence are Roslyn Poignant (in the orange jumper) and probably a Māori tour guide from Whakarewarewa. Since the nineteenth century, guides from the village have been giving tours to visitors, passing down their guiding knowledge to new generations. The guide is pointing to the scene, sharing some of her knowledge with Roslyn. This element of the photograph is important because it reminds us that the knowledge recorded by the Poignants about their transparencies was shared with them by people across the Pacific.

The beauty is in the detail

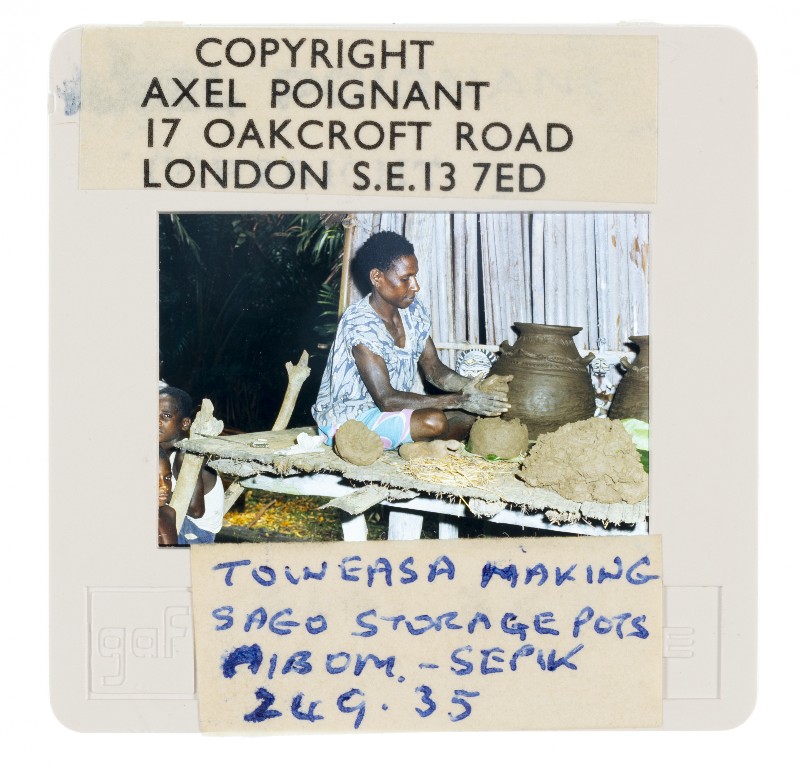

Once the transparencies have been digitised, the next step is to catalogue them; bringing together the digitised image with all of the knowledge that we have on it. As part of this process, we transcribe everything that the Poignants have written on the image mounts and catalogue cards. The mounts are very small, but they often have important information crammed onto them! On the mount for the image above, made in Papua New Guinea, the Poignants have written:

“Toweasa making sago storage pots. Aibom – Sepik.”

This tells us almost all of the important pieces of information for the catalogue: we can now record Toweasa’s name, home village, and what kind of pot she is making (sago is a food extracted from palm trees). This will be valuable for anyone interested in pottery techniques and practitioners of the area. It is particularly important that the mount records Toweasa’s name. The photographs team love learning the names of the people in the photographs we care for. More importantly, however, recording Toweasa’s name allows any of her extended community members or descendants to search specifically for her photographs.

Usually, the team write descriptions of photographs as we catalogue them. For these transparencies however, the Poignants have already written descriptions on typed catalogue cards. These descriptions often include important additional information, particularly about the relationships between people in the photographs. This card allows us to link the Poignants’ portraits of family members including this family from Raiatea: Farika, her husband Turo, and their daughter. We use the catalogue card descriptions in the database, making sure that these family relationships and other details are recorded.

Sometimes, however, the catalogue card descriptions can raise more questions than they answer. For the photograph below of two carvings at Pu’uhonua o Hōnaunau on the Island of Hawai’i, the Poignants wrote:

‘Two figures reconstructed in giant ‘ohi’a logs.’

But who are the figures? Why were they reconstructed? Starting with the Poignants’ description, the team discovered more information online through the United States National Parks Service: these are ki’i carvings of the gods Kāne and Kanaloa, carved by skilled artists from local communities in the 1960s to reflect historical knowledge of the area. This new information is now referenced in the catalogue and forms the basis for a new, more detailed description which sits alongside the Poignants’ original note.

Make your own discoveries

Now that the transparencies have been stored, catalogued, and digitised they will be cared for by the MAA. However, their journey is not over. They are a record of the Poignants’ work and reflect an enormous range of skills, conversations, and relationships involving hundreds of people across the Pacific in 1969. They are now available to view, share, and download online. Anyone who is interested in them—or perhaps might recognise the people or places in them—is welcome to get in touch with the MAA. Why not have a look at some of the transparencies on our catalogue by searching for Poignant?