COLOUR: Art, Science and Power ran from July the 26th 2022 to April the 23rd 2023. The exhibition drew from across UCM collections and explored how colour influences our understanding of the world, our emotions, creativity and relations with others. It invited visitors to discover different ways that colours are perceived, experienced and given meaning.

I worked as a research assistant on the project with Anita Herle, lead curator, focussing on the final section of the exhibition which explored the relationship between colour and the construction of identity.

https://www.museums.cam.ac.uk/blog/2023/12/22/curating-colour-art-science-power/

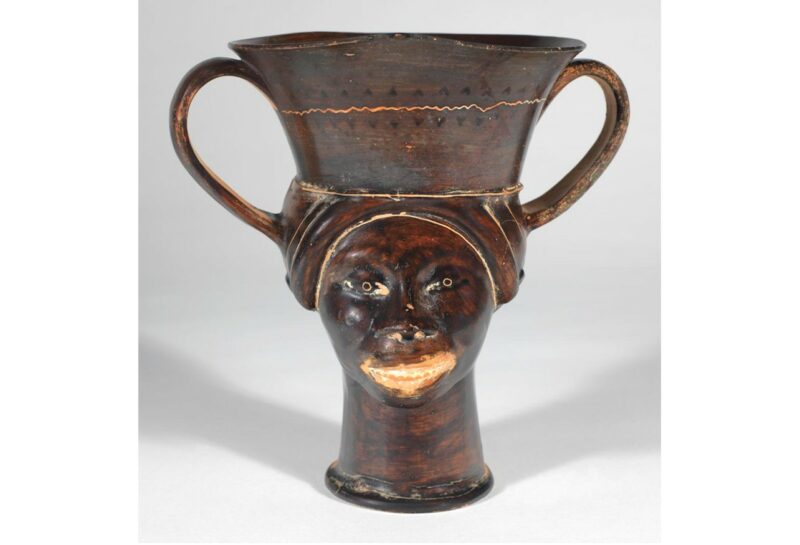

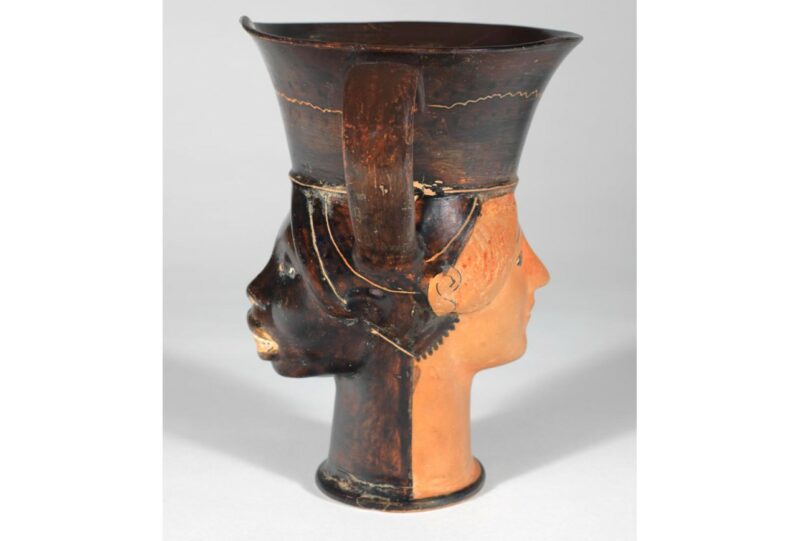

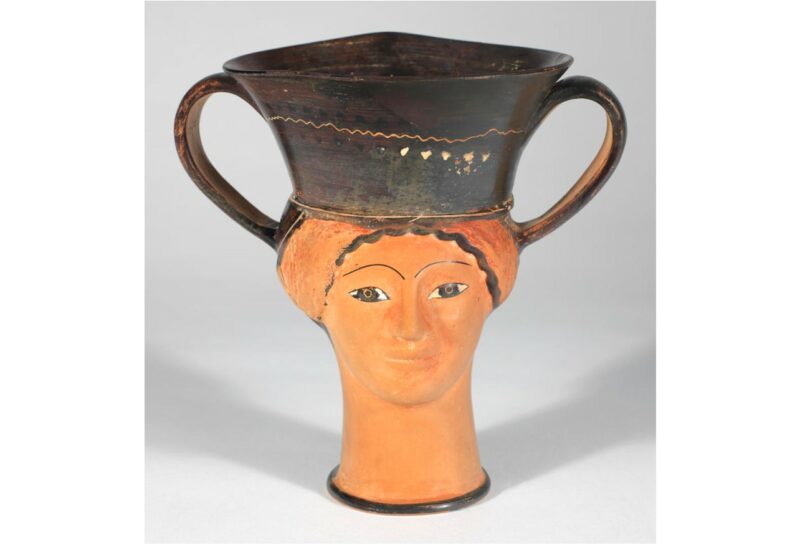

To develop this question methodology we got in contact with the UCM Community Panel and, later, special interest groups including QTI Coalition of Colour and the University’s African and Caribbean Society. In the workshops that followed we explored the use of the colours black and white as a means of categorising people. Anchoring our discussion was an ancient Athenian kantharos wine cup which had been brought to our attention by Fitzwilliam Museum curator Anastasia Christophilopoulou.

The kantharos bears two faces. Most people today would describe one face as being that of a white woman, and the other as being that of Black woman. However, we know that although the ancient Greeks used ethnic categories, these do not correspond directly with the ways that the colours black and white are used to group people today. So the kantharos tells us that whilst the person who made it and the culture which produced it were responsive to the differences in how people with heritages in distant parts of the world look, their framing of those differences was not the same as those used in the present.

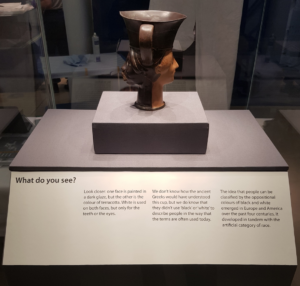

In the workshops our partners were committed to incorporating the kantharos in the exhibition, but we were concerned about its interpretation. How could we communicate that an object which appears to so explicitly demonstrate an ancient precedent for the modern Black/white divide, actually reveals that the divide is a relatively recent invention? Our approach was to produce two labels to go either side of the kantharos’ plinth. On one side was basic contextual information about the object. On the other was a label designed so that it was distinct from the rest of labels in the exhibition, the idea being that this would draw visitors to it. Less text was used than elsewhere, the type was bigger, the arrangement of the text on the label was different, and we led with a question: “What do you see?”

There were different labels on either side of the plinth. The label photographed reads:

“What do you see? We don’t know how the ancient Greeks would have understood this cup, with one face painted in a dark glaze and the other the colour of terracotta, but we do know that they didn’t use ‘black’ or ‘white’ to describe people in the way that the terms are often used today. The idea that people can be classified by the oppositional colours of black and white emerged in Europe and America over the past four centuries. It developed in tandem with the artificial category of race.”

In the first couple of months of the exhibition’s run I conducted interviews with nine visitors whom I had observed engaging with the kantharos. There was surprise that the object in the case was from Ancient Greece:

“I found it really interesting that there was a Black person represented on one side […] because that is not something I would expect to see in Greek […] artefacts.”

Interview 2

“Does that mean that there were people who looked like those two faces back in Ancient Athens? Wow!”

Interview 3

“The equality [of the kantharos] popped out to me so much, there was equality in […] the way they were depicted on each side […] I wouldn’t have thought that it was ancient Greek culture, I would have thought that it was a Black person that actually created that piece, rather than thinking that someone in Europe would have thought in that way or saw beauty in that way”

Interview 4

Some of the people interviewed were also interested to learn that the categories of Black and white as they understood them had not existed when the kantharos was made.

“I was unaware that it was only fairly recently that people were described as Black or white.”

Interview 1

“The bit about ancient Greeks not categorising people by black or whatever skin, it’s not something I’d really thought about before, I’d assumed that they behaved like we sometimes do.”

Interview 5

The revelations prompted reflections on issues around contemporary ethnic classification, with one interviewee commenting:

“[Today] often you’re labelled things in society, and they’re not necessarily labels that you want.”

Another interviewee said that although he agreed with the label, he felt that the subject of how race has been constructed needed to be engaged with in greater detail.

“I kind of wish that text was either more explicated or just wasn’t there, because I think there wasn’t enough space for the topic to be discussed at greater length.”

Interview 7

The final interviewee interpreted the kantharos in a way that we had feared might happen, doubting the veracity of the label, and instead seeing in the kantharos evidence that Ancient Greeks saw ‘Black and white’ just as he did.

“[…]the side that we are on now that says something like ‘this might not be exactly what you see’ – so this cup represents a bi-representation of a Black person and a white person, Black and white right? But then it says ‘oh yeah, this kind of division is a social concept that’s been brought into being over the past so many hundreds of years’, or something like that. Which kind of [..] made me feel like it’s an obvious, I guess, physical thing, about Black people and white people right? So I was a bit confused by that [I thought it could be] a bit of misplaced woke culture if you know what I mean?”

Interview 9

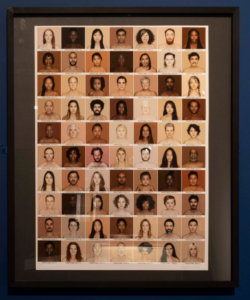

The artist Angélica Dass’ specially produced a version of her artwork Humanae for the exhibition. The background colour for each portrait is taken from the average colour across a small segment of pixels at the end of each subject’s nose. The artwork demonstrates the artificiality of categories based on skin colour. MAA number MN0269.

At other points in the interviews discussants made links between the kantharos and neighbouring displays especially the artwork Humanae (above) which was appreciated as a very effective illustration of the impossibility of using skin pigmentation to divide people into distinct groups.

“I don’t know why, I just love it. It’s very cool […] no one is truly white or black in there. So why do we have to use those words? Why can’t we just all be human?”

Interview 3

Taken collectively the interviews demonstrate that by and large, visitors responded to our presentation of the kantharos as we had hoped. Information regarding how people who today would be identified as Black were understood in ancient Greece clearly came as a surprise, and in more than one case prompted a reflection on the shifting and inconsistent nature of racial categories. The revelation that what might appear to be self-evident is in fact the product of a particular moment in history was reinforced by reference to the work Humanae as a clear demonstration of the artificiality of using skin colour to categorise people. However, the final interviewee’s confusion as well as the response of the interviewee who felt that the label was too simplistic suggest that we were, perhaps, trying to achieve too much in too little space. A display that expanded on what we do know about Ancient Greek understandings of ethnicity would have given greater weight to our argument. Equally, a parallel exhibit on the historical construction of racialised colour taxonomies would have underpinned our interpretation of the kantharos.

Ancient Greek ceramics which depict Black people are relatively common in museum collections. This display explored the potential of these ceramics to prompt visitors to question the validity of racial categories. The kantharos offered a window into a past culture that classified people through typologies which differ those prevalent today. As such it represented a powerful curatorial tool for undermining categories which are often considered to be self-evident. Without sufficient contextual support, however, its effectiveness was reduced. Any future display with similar aims, therefore, would do well share the interpretive burden which we placed on the kantharos across several exhibits, seeing it less as a standalone element and more as one element in a wider-ranging argument.