On 23 April 2024, the Gweagal Spears were returned to the La Perouse Aboriginal community at a ceremony held in the Wren Library of Trinity College, Cambridge.

On 28 April 1770, the HMB Endeavour commanded by Lieutenant James Cook arrived at Kamay (Botany Bay) in present day Sydney. This was the first encounter between the British and Indigenous Australians of the east coast.

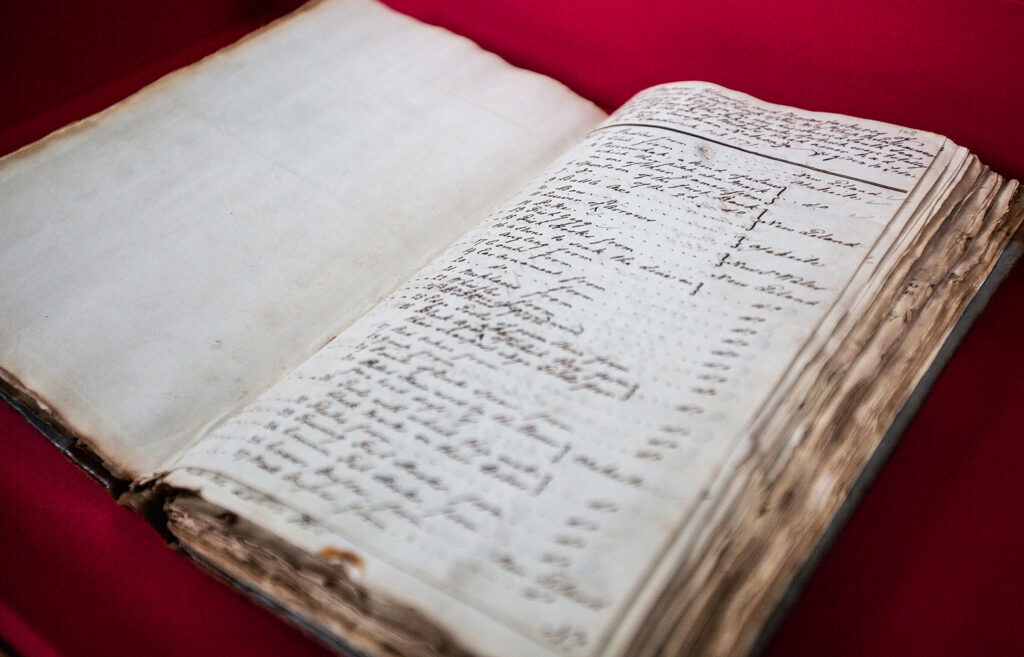

The ship’s arrival was resisted by the Gweagal people, and forty spears were taken without Gweagal consent from a campsite by members of the Endeavour crew. Only four are extant and documented today. They were given by Cook to the Fourth Earl of Sandwich, first Lord of the Admiralty, who presented them to Trinity College in October 1771.

The spears remained in the Wren Library of Trinity College until 1914 when they were deposited at the University’s Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

In March 2023, Trinity College agreed to return the spears to the community in Sydney. The decision follows a respectful and robust dialogue over the last decade between the University of Cambridge and representatives of the Gweagal people, the broader Dharawal Nation and leading community organisations, including the La Perouse Local Aboriginal Land Council and Gujaga Foundation.

An event marking the formal return of the spears took place in the Wren Library on 23 April 2024, with a delegation from the La Perouse community in attendance, as well as members of the Australian High Commission, Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, and National Museum of Australia.

As many who were involved in the ceremony expressed, the return of the spears marked an opportunity to reflect on colonial histories and highlight the role of museums as key sites for communities to reconnect with their material heritage. Returning the spears only enriches the power of the objects as well as their relationship-building potential.

The return ceremony garnered over 3,000 mentions in international media reports and has become exemplary of what can be achieved through collaborative relationships between Indigenous communities, cultural institutions, and the university sector.

Speeches from the event are reproduced below and in full on the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology Digital Lab blog.

David Johnson, member of the Gweagal Clan of the Dharawal nation:

This year marks 254 years since the Endeavour navigated its way up the eastern coastline of what we now call Australia. I want to give you a different insight to the event that had occurred all those years ago at Kamay, or Botany Bay. Today, I will share our unique insight of the view from the shore.

My name is David Johnson, and I am a member of the Gweagal Clan of the Dharawal nation. Our homelands are on the southern part of Kamay including the site were the crew of the HMB Endeavour made contact with my ancestors.

I am a direct descendant of one of the warriors who opposed the landing of Captain Cook.

Dharawal people, like all Aboriginal cultures, have an understanding and interpretation of existence, knowledge, connections and our place in the universe. We have an ontology that explains our origin and existence as spiritually founded; this is our Dreaming.

For our people, knowledge is abstract and theoretical, it doesn’t have to be scientifically proven. A spiritual explanation is logic for us.

When the Endeavour came into view, it was a confusing and surreal event.

We know from our oral history; our old people were interpreting this strange event through a spiritual lens.

Our old people wondered if the Endeavour with its billowing white sails was a low-lying cloud bringing spirits back from the afterlife.

As the Endeavour approached the shores, two men started to oppose the landing on shore. They were hand gesturing to go away while yelling out ‘warra warra wa’ which means ‘they are all dead’.

As the crew advanced on shore my old people threw stones trying to discourage the crew from advancing. In our culture it was taboo to come on someone else’s territory without permission.

The crew continued so my old people started throwing spears, but they were just landing short, this was intentional to try and discourage further entry. As they were skilled hunters, if they wanted to injure anyone, they could of done it with little worry.

As this was seen as a threat, the crew fired on my old people. They returned with a shield but were heavily overwhelmed and retreated to safety.

As the crew advanced into the old campground they noticed the canoes, spears and some of our people sheltering in their dwellings trying to avoid contact. In Dharawal culture contact with spirits from the afterlife was mostly avoided by the general community, to engage it would create a spiritual consequence.

The crew of the Endeavour constantly experienced these avoidance behaviours and couldn’t understand why our people would not engage with them over the 8 days they stayed.

As you can see, this encounter was filled with conflict, misunderstanding and lost opportunity. However, 254 years later, we are here in the Wren Library where the spears were housed after they arrived in England.

Instead of conflict we have partnership, and instead of misunderstanding we have a shared vision. Today, we all have an opportunity to celebrate these spears and what they represent for us, Australia and the whole world. Thank you.

Dame Sally Davies, Master of Trinity College, Cambridge:

This is an important day for Trinity and for all parties involved in what’s been a rewarding and respectful process and ultimately a very remarkable journey.

This journey comes, as David said, full circle with the rightful return of four Spears presented to the college by our alumnus Lord Sandwich in October 1771, soon after Lieutenant James Cook arrived back in England on HMB Endeavour following that first fateful contact with the Aboriginal people of eastern Australia.

253 years later we’ve come together to officially hand over these artifacts of immense significance to the La Perouse Aboriginal community whose ancestors made them and from whom they were taken.

We would like to thank all those who’ve taken part in good faith in the discussions and exchanges that have enabled us to reach this point.

When Trinity and the La Perouse Aboriginal community announced their joint endeavour a year ago, the reception was overwhelmingly positive. This is the right decision. Our interactions with the La Perouse Aboriginal community, the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology in Cambridge, the National Museum of Australia and the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander studies have been truly inspiring, and we look forward to the ongoing collaboration.

Professor Nicholas Thomas, Director of the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology:

Over the last ten years there has been renewed, often polarised debate about the return of cultural heritage. Some people think nothing should go back. Other people think everything should go back. Some people think treasures cannot go back because they will not be well cared for. Others think that artefacts should go back so that they can decay naturally. In this case, all the stakeholders have an absolute commitment to the care and preservation of the spears, now and in the longer term.

Dialogue between the La Perouse community, the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology and Archaeology, and Trinity College started with that in common. We’ve carried on a conversation, that’s involved honesty, respect, friendship and a shared interest in broader research, which also has involved other museums and universities.

Some people think museums are places of the past, but all the curators I know are preoccupied with the potential and power of collections in the present. The power of these exceptional historic artefacts will be enhanced on their return to Australia, and that return will strengthen the relationships between Cambridge and Indigenous Australia.

[Addressed to the La Perouse representatives] I look forward to welcoming you back, so that we can carry on our work. In the future, my successors at the Museum will welcome back your children, as visitors, as students, as researchers. You will always have a connection here.

Noeleen Timbery, Chairperson of the La Perouse Local Aboriginal Land Council:

Good morning, ladies and gentlemen. I want to start by acknowledging Country and paying respects to Elders past and present.

Our people use the word ‘Country’ to describe the lands, waterways and seas that we are culturally, spiritually and traditionally connected to. And back home we perform a Welcome to Country or an Acknowledgement of Country as a modern-day interpretation of our ancient cultural lore of seeking and granting permission to enter lands that are not our own.

And we are a long way from home; from our Country.

But these beautiful spears have been resting on this country here in Cambridge for over 250 years, so we acknowledge these lands on which they have been. Just as we will soon welcome them back to Country and to the lands where they were created.

Getting to this day has been a long journey for our community, and there are many people we need to thank.

Firstly, the NMA – the National Museum of Australia were early partners in our journey toward today, and they have provided great expertise, support and advice to our community with regard to the spears and caring for cultural objects. The NMA has worked respectfully with our community to showcase our history and the stories of our ancestors. They were integral in making it possible for the spears to return to Sydney (on loan) 2 years ago, which was the first time since they left the shores of Kamay in 1770. And they have continued to work closely with us on our work toward the spears being returned home for good.

We also thank AIATSIS – the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. The help and support AIATSIS has provided through their Return of Cultural Heritage program has been immeasurable.

By helping us navigate the complexities and legalities of repatriation, we were able to build confidence in the process and focus on what was important – showcasing the resilience of our people, our continued unbroken connection to country and culture, and ensuring our community had a voice.

Trinity College, and importantly the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. We thank you for the care you have provided for these many years. Nick, you really do deserve more than our thanks. This we couldn’t have gotten to today, without your help and support. So, I do I want to thank you from the bottom of the heart and on behalf of our community.

Our Elders acknowledged many years ago that without that care these spears would not exist today, and the connection we feel would have been lost. Our Elders passed down this knowledge and so we honour that too.

I was fortunate to travel here to Cambridge in 2017 alongside Dr Shayne Williams, respected Gweagal Elder and cultural educator.

We visited the spears and other cultural objects, and we spoke with staff and students about their cultural and historic importance, the continuing cultural practice of spear-making and the role these spears have in educating both about where they came from and how the practice of spear-making has evolved.

Shayne had first contacted Trinity College about the spears about 22 years ago, and our visit in 2017 was an important part of building an ongoing relationship with the college and the Museum.

Now Shayne isn’t here on this trip with us, but he of course is a big part of how we got here. He has proudly wished us well and in line with our practice of passing down knowledge and responsibility, he has handed this work on to his Grandson Quaiden who is part of our delegation.

There have been many discussions since that visit in 2017, and our relationship has continued to grow and strengthen.

And so we thank Trinity College and the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology for their commitment to work with our community, now and into the future. And most of all we thank them for understanding that after 254 years, it was time for the spears to return home.

We want to assure everyone here today that the significance of this moment, this “handback” has not been lost on any of us. These spears connect us culturally, spiritually and tangibly to our ancestors; they are survivors from a moment in time that marks the beginning of the shared history of Australia. They are significant not only to us and our community but to all Australians. And they are coming home.

The spears will return to a new home in museum grade facilities within a new visitor centre being built in the Kamay Botany Bay National Park in Sydney, very near to where they were taken from. They will be showcased and celebrated on country for all to visit and enjoy.

We will protect them. We will care for them. We will cherish and honour them. And we will ensure that they and their story is shared for many generations to come. Thank you.

As the speeches testify, the return of the spears was a truly momentous occasion. These objects hold immense significance today and will forever link Cambridge with communities in Australia. The relationships brought into being by the spears will continue for posterity, with the meaning and value of the material enriched by their return.