Plaster casts aren’t just small objects which sit in tidy museum storage drawers. Oh no. Here at Museum of Classical Archaeology (MOCA), we have some pretty big plaster casts – and some of them are hung up really quite high on the walls. So what happens when we need to access them for essential conservation work? Read on to find out.

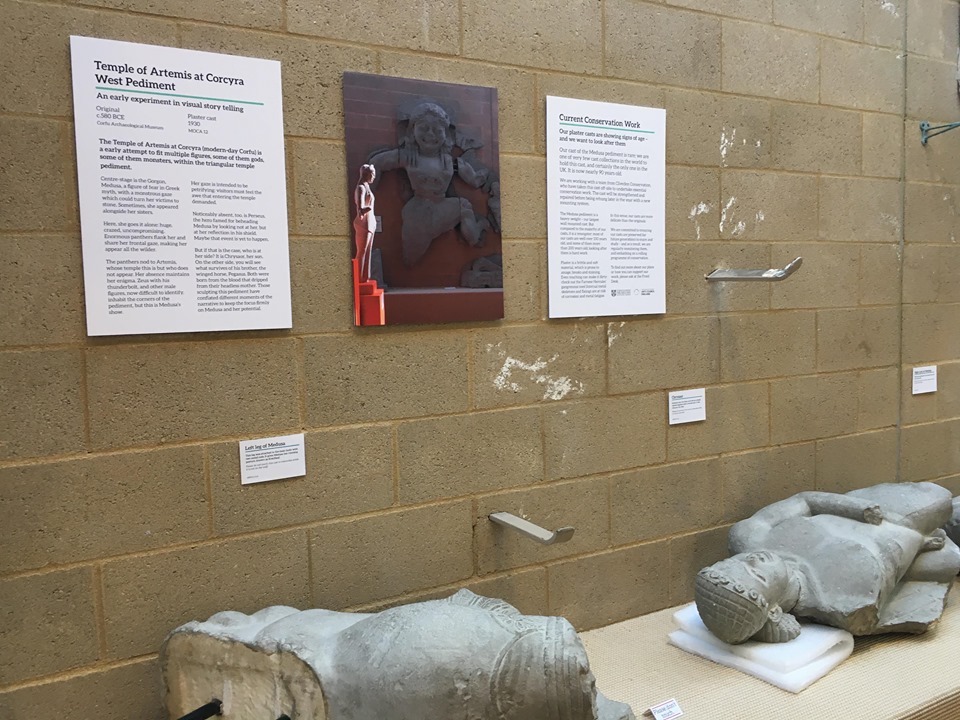

The huge west pediment from the Temple of Artemis at Corcyra on Corfu is one of the most striking casts in the Museum of Classical Archaeology’s collection: the grimacing figure of Medusa stares down visitors almost as soon as they enter at the Cast Gallery, snakes wrapped around her waist and flanked on either side by two enormous panthers or leopards. It is an object both beloved and rare; no other collection in the UK has a cast of this same pediment. The central figure, Medusa herself, stands around about 3.5m high – or, rather, she hangs, on the wall in Bay A, the first Bay you encounter when you enter the Museum.

The Medusa pediment is an object both beloved and rare; no other collection in the UK has a cast of this same pediment. But can you imagine our Cast Gallery without it?

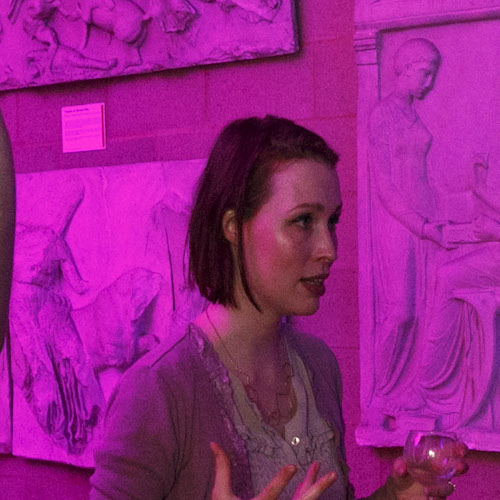

If you had visited MOCA in Michaelmas term of 2019, this is exactly what you would have seen: an empty wall, devoid of the central Medusa figure. Some of the smaller parts remained, strewn along the central bench instead of mounted in their usual hanging position. But Medusa herself was gone.

In November 2018, we undertook a condition survey of our high hanging casts. The casts had all been mounted when the collection moved into the current building in 1982, and they were too high above our heads for us to get a good enough look to assess their stability.

Those two weeks atop a mobile scaffolding tower revealed that the cast of Medusa herself had certainly seen better days: the huge central figure was developing cracks, mainly through the neck but also snaking through the rest of the body. It was clear that it would need to come down for essential conservation, and that the cast would also require a new mounting system in order to ensure the long-term preservation of the object for audiences in the future as well as for the safety of our visitors.

But this left us with a problem. The Medusa is enormous – the single largest wall-mounted cast in the entire question. We had no easy way to access her, let alone remove her from the wall. We needed help: this was definitely a specialist job. We contracted a specialist team at Cliveden Conservation to undertake the work, who specialise in handling and repairing large-scale plasterwork, to begin in September 2019.

The work to remove the cast from the wall would take a week – and it was not a task for the faint hearted. Not only was the figure of the Medusa big, but although we knew it was hollow we could be certain neither of its weight nor of its existing mounting system until we removed it. A decision was made to build a wooden frame around the cast while it was still on the wall, which would both support it during removal and conservation, and would also form the foundation of the crate used to protect it during transportation. The primary aim was to prevent further damage during the removal, since it was inevitably going to exert new pressures on the whole cast.

By far the hardest job was lifting the cast from the wall itself. The smaller cast fragments surrounding the central figure were removed first; the weight of the arms and legs had been hanging on metal struts inserted into the main body, with no additional brackets to help take the weight. It took an hour to nudge the body of Medusa, inside the frame, from the fixings upon which she was hanging using a hoist built by the Cliveden team in situ – and when it finally came free, it seemed to jump from the wall with an energy all of its own! The frame had done its job, supporting the cast so that there was no further damage, but the source of the cracks became clear: the heavy central figure had been gently rotating on its fixings in the c.35 years since it had been mounted, creating stress points at the neck and elsewhere.

The cast was removed to Cliveden Conservation’s workshop in Houghton (Norfolk) for repair. A purpose-built steel frame was inserted in the back to add additional support – and would also double-up as a mount when it was rehung on the wall. Cleaning and the filling in of the cracks would be undertaken as a final job, when the cast was safely remounted. We now not only have a new mounting system, which better supports the weight of the whole cast as well as the additions – but we also have better records, including both a detailed report outlining the current mounts and the weight of the central figure plus the new frame. This type of record keeping is really essential to ensuring the proper care of the objects not just now, but also in the future.

This conservation project gave us an opportunity to reconsider the label for the Corycyra pediment, creating a model which gives information about both the cast and the original which we hope to roll out throughout the Museum in the future. It also allowed us to learn more about the cast itself. On the back, we found the date ‘FEB 1930’ inscribed into the plaster – we know the cast was purchased in 1930, ten years after the original was discovered in 1920, but we don’t know where from. However, since we found English-language newspaper embedded in the plaster, we can probably rule out a European workshop.

The Museum of Classical Archaeology has now committed to an ambitious rolling programme of replacing and improving the fixtures for our wall-mounted casts. The majority of our casts date to the nineteenth century and they are now showing signs of age – and so we are committed to preserving our collection for future generations to enjoy.

As for Medusa herself: she was finally returned in the first week of December, without any further difficulties. If you visit now, she’s back looking out at you, waiting to turn you to stone…