Here’s how a repaired Naga body cloth from India can provide inspiration for mending your own socks.

As part of the Stores Move Project, the team at the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (MAA), the team has recently been processing textile collections from India, preparing them to move to our new store.

You can learn a lot about the way textiles were made and used by looking at them closely: how they were woven, what choices were made about materials and where they became worn through use. My favourite textiles are often those which have repairs. Repairs suggest that an object was highly valued and that the user(s) wanted to extend its lifespan. They’re a glimpse into a much more personal aspect of collections, letting us connect with people who interacted with objects before they entered the museum collection.

It’s also a rich area for inspiration. As many people are turning to repair as one way to address climate change and consumer culture, I find myself being drawn to repaired objects for inspiration and encouragement. Repairs don’t need to be perfect; in fact they’re far more characterful and endearing when they aren’t!

Naga Body Cloths

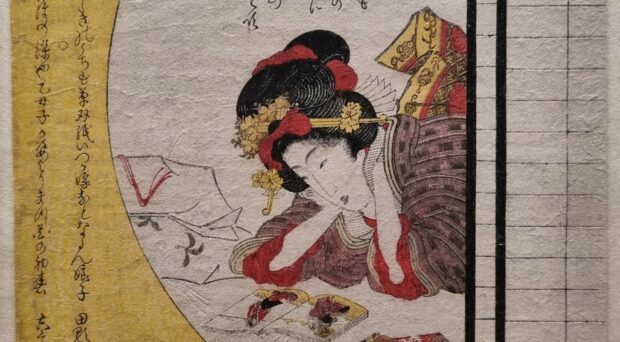

MAA cares for around 100 Naga body cloths and skirts. These are rectangular cotton cloths made up of one or more strips woven by women on a loin loom, also known as a backstrap loom. They are often decorated with dyed red dog hair and cowries, sometimes with the addition of painted panels, dyed goat hair tassels, iridescent green beetle wings, or red cane and yellow orchid stem elements. The varied designs indicate the wearer’s cultural affiliation and status within their group.

Some of the body cloths at MAA were displayed and documented as part of a 1990-1992 exhibition called The Nagas: Hill People of Northeast India. Many others had been photographed in 2015-2016, in a previous move of textile collections due to deteriorating conditions in the store. You might think, then, that they were already fully documented. What could we add to the records?

From top left: MAA 1947.224, 1947.191, 1947.225, Z 46942, 1978.158 and 1947.249.

Museum priorities, standards of collections documentation and available technologies are changing all the time. The current iteration of MAA’s database was not in use when the Naga exhibition happened, or even when the textile move occurred. The facilities available to the museum team in the past did not allow for well-lit, top-down photography of many collections, let alone large textiles, so new photos were needed.

Historic descriptions were minimal and often simply stated the object name, sometimes along with colours and decorative motifs. Drawing on publications we were able to update description with local names, accurate terminology and current research.

In addition to changes within the museum world, new ideas and concepts are constantly being explored: textiles as signifiers of identity, craft production as an art form, varying forms of gender expression and so on. Recent concerns about climate change and focus on sustainable living have also led to a rethinking of fast fashion and a resurgence of repairing, reusing and upcycling. Making and mending, therefore, are often on my mind when I work with collections in the museum.

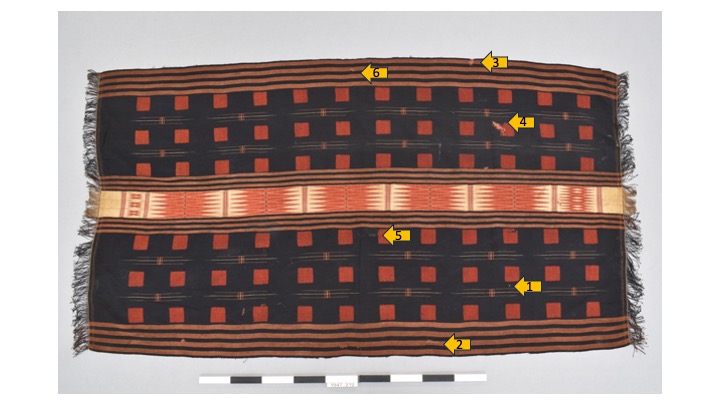

A repaired body cloth

Defining and describing repairs is tricky. Was it a contemporary repair? Contemporary to what? Were all the repairs done at the same time? Is it a local repair? Is it an indigenous repair? Was it carried out by the original maker or wearer? Or was it post collection, done by an enthusiast or a museum professional?

Most of the time we aren’t able to answer these questions, but we can make some assumptions – and produce a whole new set of questions in the process!

The repairs have been done with thicker thread than the original weave, so we can assume that they were done after a period of use and possibly not by the original maker of the cloth. From the detail photographs of 1947.212, we could suggest that the repairs were carried out with varying levels of skill, or at least level of time invested.

Repairs 1 and 2 appear to have been done carefully, with an awareness of how they would affect the appearance of the cloth. Repairs 3 to 6 seem somewhat more functional – the main priority being to hold the torn edges together. In most instances, the repairer seems to have chosen a thread which is reasonably colour-matched, although this isn’t the case in repair 4. Why?

Finding inspiration

A few years ago, I started becoming interested in the possibility of mending my own clothes. Like many people, I was daunted by the skills I thought I would need to achieve invisible mending, or the creativity I would need to make visible mending ‘look good’.

Working with repaired objects like this one in the collection, reminds me that there is no single or correct way to do a repair. I enjoy seeing the variety and ingenuity on display – a strip of cane used to repair a broken gourd (see MAA Z 24639), a patch of leather used to fix a hole in a bag (see MAA 1937.857 and Digital lab blog), or a piece of carefully shaped cork used to reconstruct a pottery vessel (see MAA 1905.291).

I started with simple, small darns to avoid throwing away some of my favourite or most comfortable clothes. To start off with, the repairs weren’t very skilled, and I have revisited many of them. As I’ve grown in confidence, though, my repairs have become more effective and visually appealing. From covering up moth holes in jumpers, to threadbare patches on socks and even to resizing bras – practice makes perfect.

When I see repairs in the collection, I no longer simply add: ‘contemporary repair’ to the description, I also look at them closely to understand how it was done and what I might learn for my next mend.

What’s next?

Inspired to mend? Why not grab a pair of socks and start experimenting! All you need is a needle, thread or wool and something to keep the fabric taut (darning mushroom, glass or jar). There are plenty of free resources including how-to guides and videos online.

To find repaired objects on MAA’s online database, try searching ‘repair’ or ‘contemporary repair’. You can also use an advanced search to narrow down your results by Place or Material.

For more about repaired objects, take a look at Lucie Carreau’s blog, Scars and stitches, or to read more about what can be learnt from broken objects, check out my MAA Digital Lab blog on beadwork.