1. Introducing the Exhibition

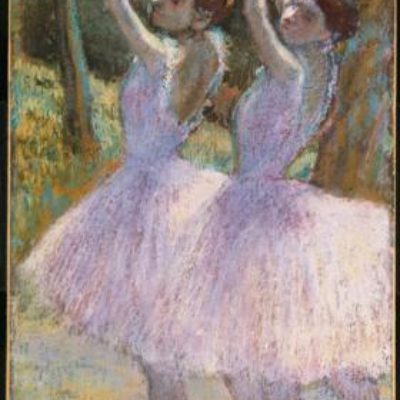

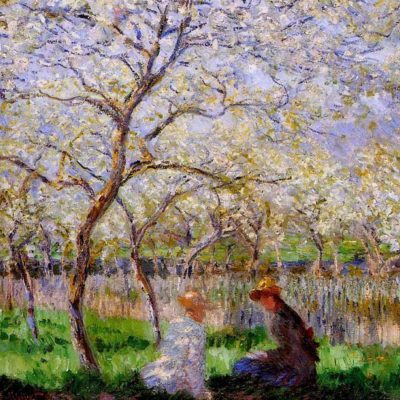

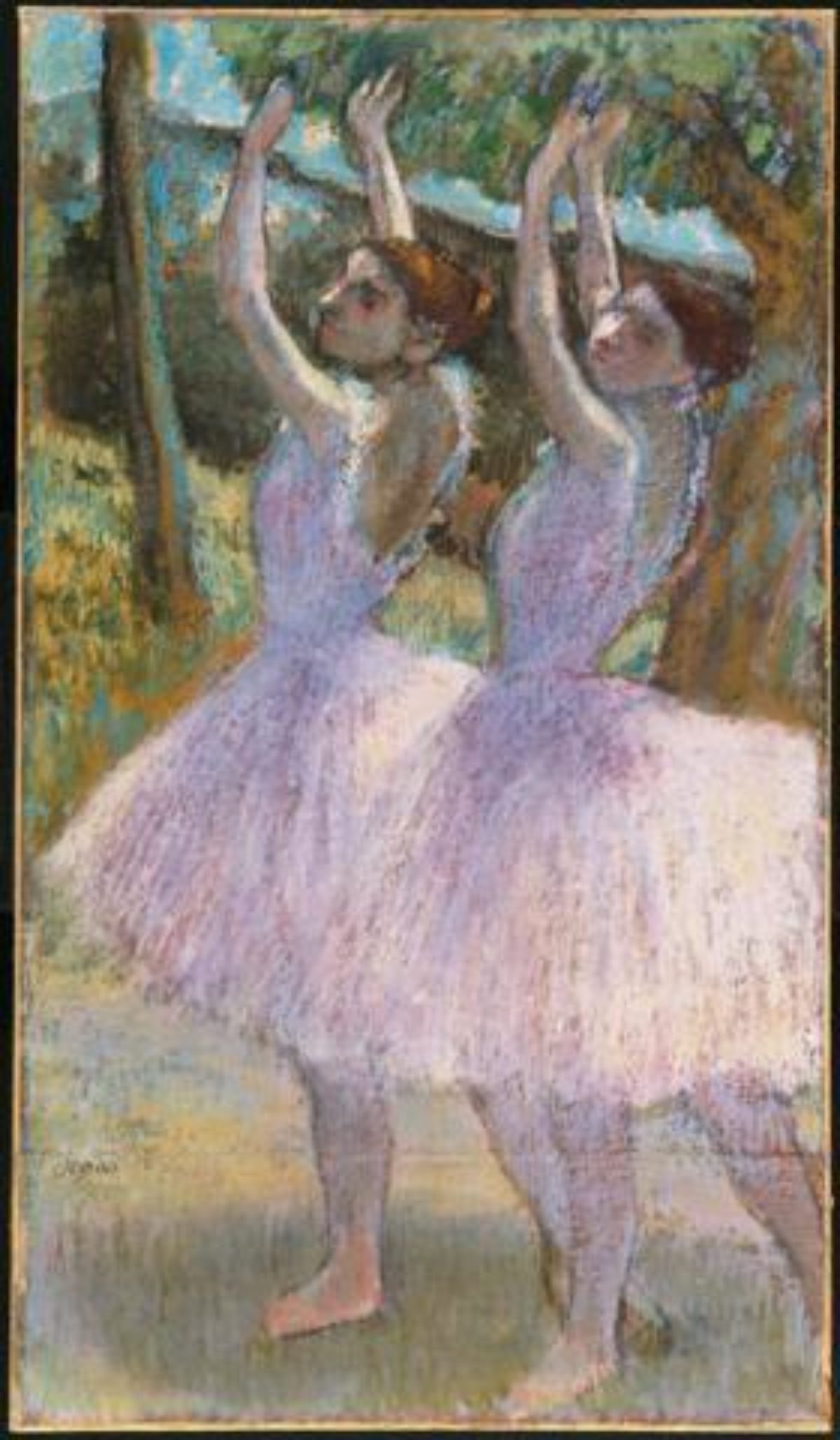

In Autumn 2017, The Fitzwilliam Museum hosted an exhibition celebrating the work and study of the French artist Edgar Degas, titled Degas: A Passion for Perfection. Degas is most well known for his work studying dancers but he was a prolific artist and was interested in landscape, travel, the classics and cafe scenes. He explored these different themes through a variety of different materials and technqiues from mono-printing to sculpture, painting, drawing and printmaking.

‘We must chat, it’s the only way’

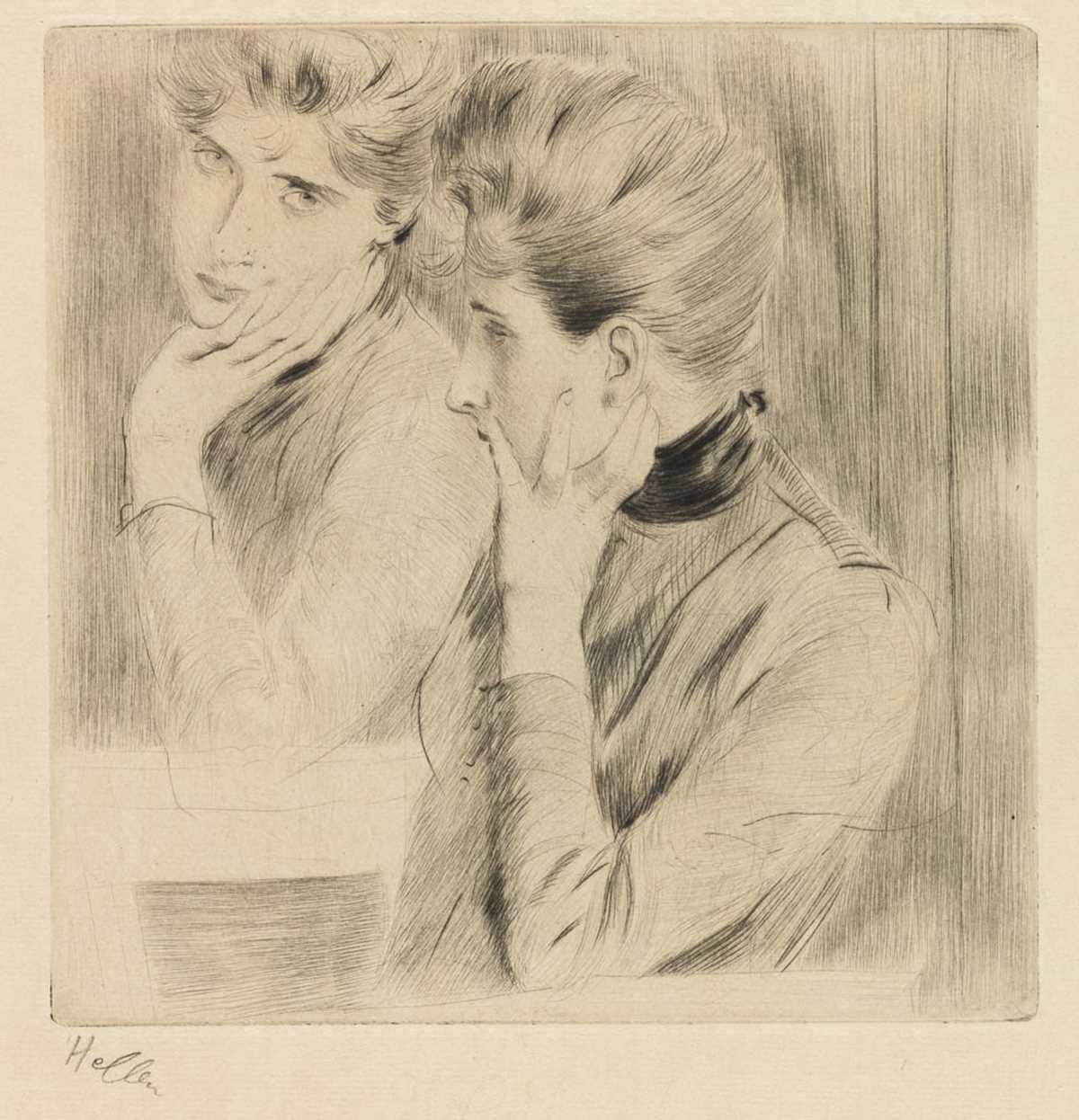

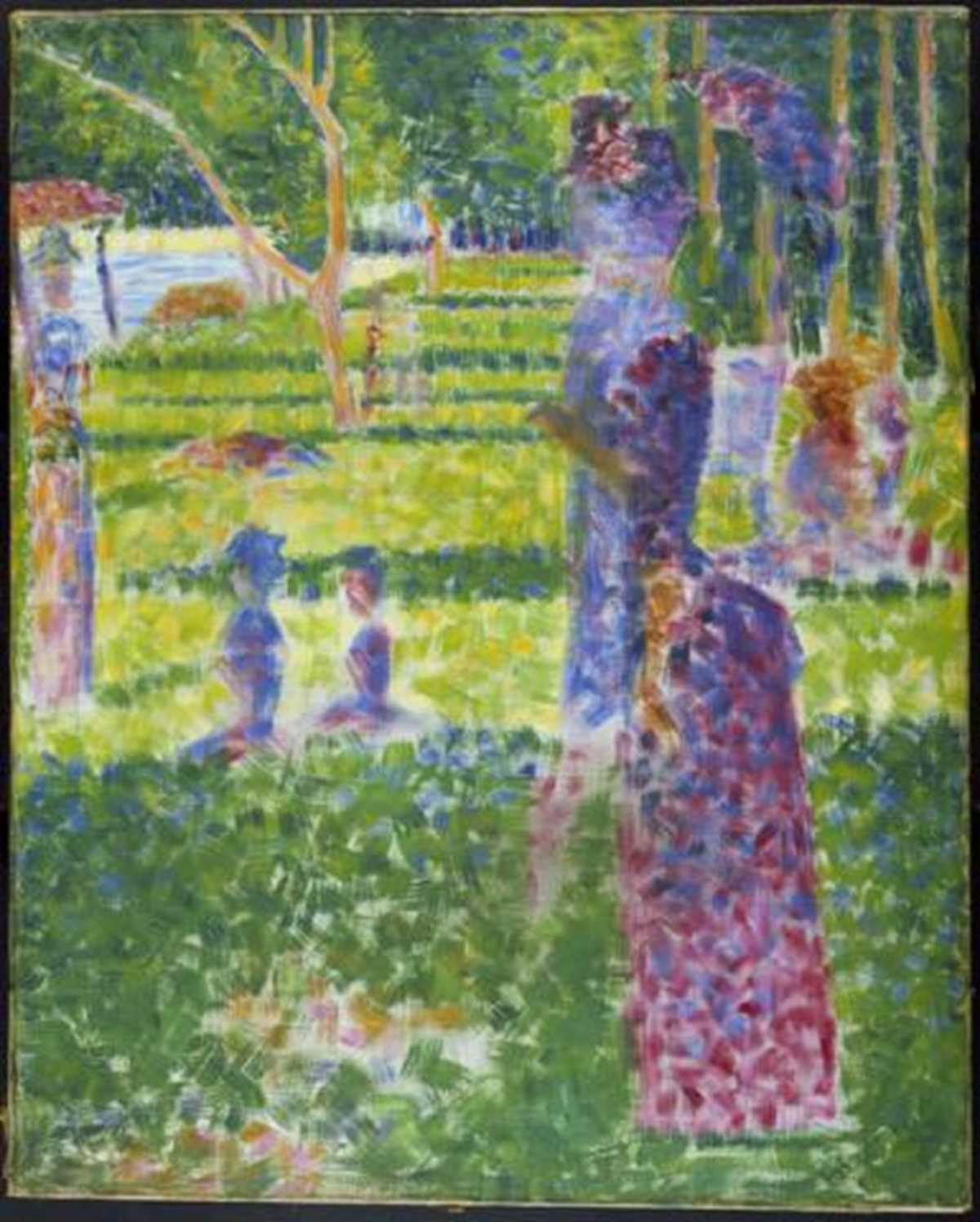

Degas c.1879

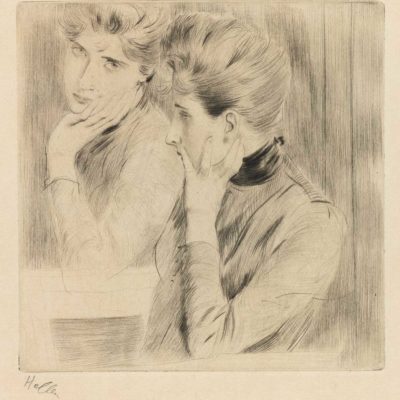

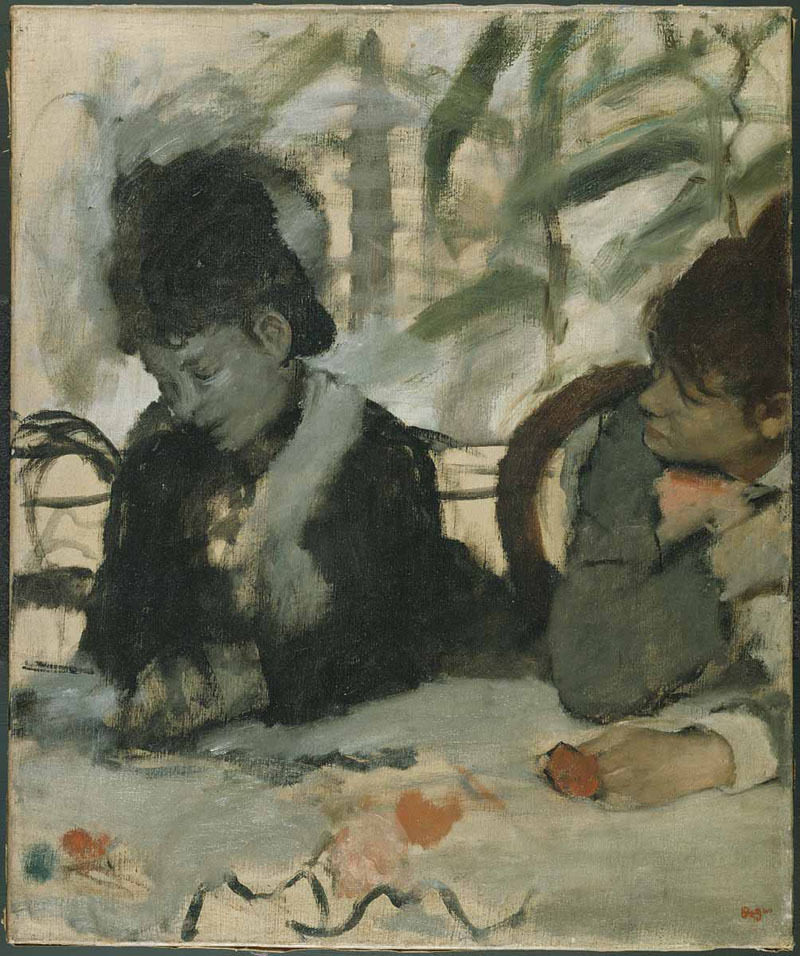

Degas carefully observed people in the places where he and his friends spent time. During the 1870s and 1880s he made a series of pictures which depict women chatting, sometimes with a member of the opposite sex, but more frequently with one or more other women. Most, but not all, bear the title ‘Conversation’ or, ‘Causerie’. 'Causerie' is derived from the French verb 'causer', which is generally translated into English as ‘to chat’, although some of the subtleties of the term are lost in translation.

This painting is called ‘Au Café’ and formed part of the Degas exhibition at The Fitzwilliam Museum.

Click on the thumbnail in the top right of the screen to download a high-resolution image of the painting.

ACTIVITY 1

TAKE A LONG, CAREFUL LOOK AT THE PAINTING

SPEND 5 - 10 MINUTES NOTING DOWN EVERYTHING THAT YOU CAN SEE.

What are your immediate reactions to the picture?

Make a quick list of any initial questions you would like to ask.

ACTIVITY 2

Now watch Jane Munro, Keeper of Paintings, Drawings and Prints at The Fitzwilliam Museum, talking about the painting.

Jot down any additional ideas about the painting.

You can see the outline of trees in the background of the painting. This indicates that they are either sitting outside or in front of a large window. Both figures appear to be seated at a table. You can make out the edges of the chairs behind them and they are resting their arms on the table in front of them. The painting was kept in Degas’ studio until after his death and when it was exhibited for the first time it was titled, ‘deux femmes attablées (‘two women seated at a table’). The title of the painting ‘Au Café’ translates as ‘At the Café.’

The two people in the painting appear to be talking. It is difficult to see what is on the table in front of them but one of them is holding something red which might be a flower. There was a fashion at this time for decorating tables with cut flowers. The person on the left is hunched over gazing down at her hands, avoiding eye contact. She appears distracted and world weary, disinclined to make eye contact with her companion who looks on intently and – one imagines – sympathetically, as if hanging on her friend’s every word. Her companion leans on her left arm and is looking directly at her face. Her right arm is across her body.

There are lots of things we would like to know about these two ladies but the painting does not give us much information. We do not know who these people are as they are not named by the artist as they would be in a more formal portrait. In this instance, the subject of the painting is not the people, but the conversation in which they are so deeply engaged. The expression on their faces and body language are both intriguing and perplexing. Much of the difficulty in deciphering At the Caféarises from the fact that Degas left the painting unfinished. The background setting is only hinted at through a series of tentative brushstrokes, while the women’s partly-concealed expressions are barely legible, hard to define. We must work out what we can from their gestures, the turn of their heads, and apparent direction of their gaze.

Degas had many unfinished works of art in his studio as he would often return to work on a piece over many years. He would build up his paintings in layers and to start with monochrome ‘under-painting’ to fix the broad lines of a composition, and also to establish tonal relationships and light effects. Colour would then be applied on top of this to add depth and detail. In 1893 he gave his student, Alexis Rouart, the following advice.

‘You see… you paint a monochrome ground, something absolutely unified; on it you put a little colour, a touch here and a touch there, and you will see how with nothing very much one obtains a sense of life.’

This gives us a good idea of how Degas worked and helps to explain why Au Café appears in this way.

2. Friendship in Nineteenth Century France

Friendship is everywhere. It is almost impossible to imagine a society or culture without it. Yet for a concept that is so immediately, intuitively meaningful to virtually all human beings, friendship has been a famously difficult to study. Unofficial, uncodified and unregulated (not to mention, very often, unspoken), friendship is not easy to define; nor do the friendships of the past necessarily leave traces that might allow us to put together a model of historical friendship.

Over the last twenty years, the challenge and the possibilities promised by these problematic aspects of friendship have made it an interesting and productive field of study, across a number of disciplines. Historians and literary critics have been drawn to the theme for different reasons, and have addressed it in different ways - but they have rarely had the opportunity to compare their basic assumptions about friendship, and in so doing work out if they are even talking about the same thing.

Researching Friendship in 19th Century France

Find out more with Nick White, Professor of Nineteenth- Century Literature and Culture

Our AHRC funded research project brought together historians and literary scholars from France, Canada, the UK and the USA to create an interdisciplinary network exploring the cultural history of friendship in nineteenth century France. We hoped that by studying the peculiarities of nineteenth-century ideas on friendship we would learn more about our own assumptions and blind spots around this everyday theme.

In the first instance, we set out to consider what presuppositions about friendship operated within each of our own fields of expertise and academic context, in order that we might to explore what we might learn from each other. We were particularly interested in seeing what new forms of evidence we might discover through an interdisciplinary conversation, and how this evidence might enable each project partner to enrich their own account of this central cultural question.

Our network investigated the following themes: friendship as a public and private issue, friendship as a cultural phenomenon and a fact of life and friendship as representation and reality .

In the early stages of project planning, we talked to each other about what we were most interested in exploring in order to help to formulate our research questions. This first stage took some time and many long conversations but it was vital to the success of the project to be clear about what we were aiming to do.

These were some of the questions we asked:

- Could nineteenth-century (heterosexual) men and women be 'just friends'?

- Could nineteenth-century literary texts represent such a friendship, whether possible or not in real life?

- Would a novel in which the characters were bound exclusively by friendship, and from which sexual desire was excluded, even be readable?

All of these questions flowed into our collaborative exploration of what friendship meant to different people in nineteenth-century France and helped us to explore what new things an analysis of 'friendship' can tell us about this supposedly familiar context.

One way of thinking about sexual identity in our own society and culture today is to compare and contrast it with the dynamics of other times and places, and nineteenth-century France presents a good example of an age torn between norms and innovations in all spheres (following the French Revolution of 1789), including that of sexual identity. The nineteenth century used a vocabulary of sexual identity which me recognize, even if we don’t necessarily use all the same terms and categories in exactly the same way today, Indeed, by the end of the nineteenth-century Europe the terms ‘homosexuality’ and ‘heterosexuality’ had come to the fore, as a way of differentiating between forms of romantic and sexual attraction and between types of relationships – most famously in Richard von Krafft-Ebing’s highly influential 1886 book Psychopathia Sexualis. The prefix ‘homo’ comes from the Greek word ὁμός (or homos), meaning ‘same’; and the prefix ‘hetero’ comes from the Greek word ἕτερος (or héteros), meaning ‘other’ or ‘different’. A century later (in the final years of the twentieth century), thinkers started to see how useful this language of sameness and difference could be in thinking about the relationship between our sexual identity and other types of identity we display in society.

SEXUAL | SOCIAL | |

HOMO | A term now largely displaced by modern LGBTQ+ vocabulary | Homosociability (or homosociality) means same-sex relationships that are not of a romantic or sexual nature, such as friendship or mentorship. |

HETERO | A way of talking about the dominant or ‘normative’ sexual ideology, often associated (not least in the nineteenth century) with norms of heterosexual marriage, reproduction and the ‘traditional’ family. | Heterosociability (or heterosociality) refers to social relations (such as friendship or mentorship) with persons of the opposite sex which are not of a romantic or sexual kind. |

Of particular importance in thinking about how literature could be thought about as a space in which societies both confirm and question these patterns of sameness and difference was Eve Kosofsy Sedgwick’s book Between Men: English Literature and Male Homosocial Desire (New York: Columbia University Press, 1992 [ first published in 1985]). But we could apply this homo/hetero + social/sexual matrix to all sorts of stories from film, t.v. and elsewhere. Sedgwick (a modern critic) considers how we can write about the role of sexual difference in all manner of human activities using these notions of homo and hetero, but applying them beyond the sexual realm (hence the terms homosociability and heterosociability). If we want to understand the power relations between men and women in images or texts, then thinking about them in terms of these four terms (homosocial, homosexual heterosexual, heterosocial) give us a useful vocabulary with which to do so. Historians and critics will often argue that traditional patriarchies often depend on a collusion between heterosexuality and male homosociability (in other words, between the reproduction of sex and of power). The classic Victorian wedding day would be a good example of this, the father handing his daughter to the groom. Is this set-scene, a gender historian might ask, simply about the heterosexual contract, or just as much about the homosocial relationship between men (between father-in-law and son-in-law)? And thus a way of keeping the traditional order of things in place. Creative writing and visual culture can be powerful ways of representing, but also questioning, such tradition. Perhaps the most “political” moment in Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary is not her heterosexual adultery (which is, after all, a cultural cliché in Flaubert’s eyes) but rather her despair at the idea of replicating herself (homo meaning same) in the form of a daughter (who will face the same social constraints as her mother). In Degas’s painting, many of the questions we have been asking (what is the nature of the relationship between these women? Are they just friends? What are they talking about? Are they prostitutes, and if not what is their occupation? Is this a lovers’ tiff?) turn on these questions of the homo and hetero, and of the social and sexual. Because these terms are not fixed in the painting, nor are the answers to our questions.

Creative writing and visual culture can be powerful ways of representing, but also questioning, such tradition.

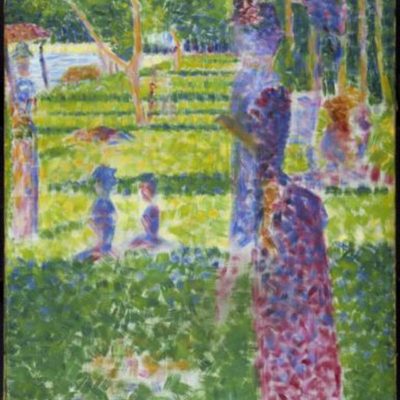

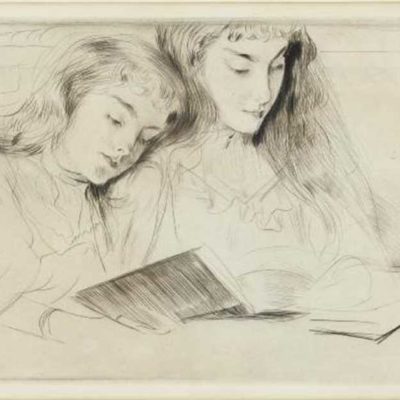

Over the course of our research project we studied hundreds of literary texts and images from nineteenth century France.

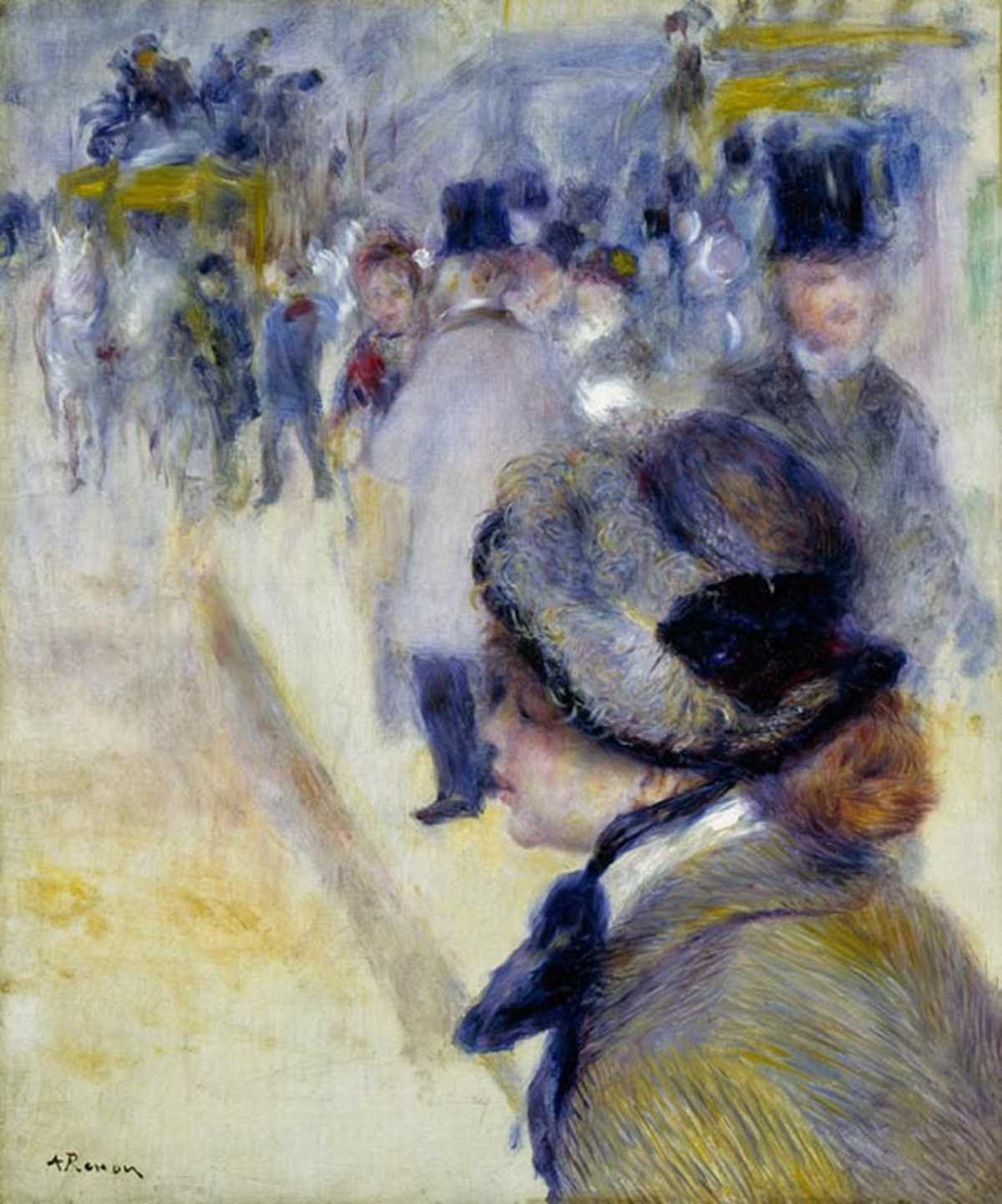

In the next section we will look at how a painting by the French artist Pierre-Auguste Renoir helped us to explore some of our questions.

Analysing the relationships between men and women in Renoir's La Place Clichy

Find out more about La Place Clichy here.

3. What does other French 19th Century Art and Literature tell us about friendship at this time?

Challenge 1 with Professor Nick White

Select a text or image from the carousels below and think about:

Who is the main subject?

Whose story is this?

How is the art/ writer encouraging us to adopt their point of view?

What does this image or extract tell us about friendship at this time?

Where would you place this on the homo/ hetero & social/ sexual matrix?

These 19th Century French texts include representations of heterosociality.

You can read them in French or in the English translation.

The last series of texts detail homosexuality in 19th Century France.

Henri de Latouche, Fragoletta, ou Naples et Paris en 1799 (extract)

4. What next?

Challenge 2 with Professor Nick White

Think of an example of a work of art, a book, a film, advert or television programme that you enjoy.

What does this tell you about attitudes to friendship, identity and sexuality now?

What has changed?

What has stayed the same?

5. Further Reading

Munro, Jane. Degas: A Passion for Perfection, Yale University Press/ The Fitzwilliam Museum, 2017

Counter, Andrew and White, Nicholas (editors), “The Art of Friendship in France, from the Revolution to the Great War”, special number of the journal Romanic Review, Volume 110, 2019

The sources which show how the terms homosociability and heterosociability can be used in cultural analysis, and which originally shaped our project on friendship, are:

Marcus, Sharon. Between Women: Friendship, Desire, and Marriage in Victorian England. Princeton: Princeton UP, 2007

Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. Between Men: English Literature and Male Homosocial Desire. 1985. With a new preface by the author. New York: ColumbiaUP, 1992.

White, Nicholas. ‘The Lost Heroine of Zola’s Octave Mouret Novels’, Romanic Review, vol. 103.1-2, 2012, pp.369-390

Credits

This AHRC funded project had its origins in the nineteenth-century research and teaching group of the French Section in the Cambridge European Languages Faculty (the Faculty of Modern and Medieval Languages and Linguistics) at the University of Cambridge. The Principal Investigator, Nicholas White, designed the project with Andrew Counter, and they have co-edited the subsequent collection of essays to which colleagues from the group, Edmund Birch and Claire White, contributed. As the project unfolded, its literary and historical perspective widened, as it became clear that it could dovetail with the Fitzwilliam Museum’s exhibition on 'Degas: Passion for Perfection', curated by Jane Munro, which brought into focus the question of how a necessarily silent visual image such as Au Café might address issues of friendship, sociability, language and conversation. Another member of the nineteenth-century French group, Rebecca Sugden, has worked with Kate Noble of the Museum’s Education Department to create this resource and to think about how these research questions could be applied to other texts and images, in and beyond nineteenth-century France.

Images copyright of The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge