1. Planning Your Project

Why this object?

Manuscripts were the forerunners of today’s books, made out of treated animal skin (known as vellum) – rather than paper. The word ‘manuscript’ means that it was written by hand. Manuscripts covered a wide variety of topics from across the world. The Southampton Psalter is one of these many varieties of manuscript.

The Southampton Psalter (C.9) dates from around 1000AD, and it is the oldest manuscript in the library of St John’s College at the University of Cambridge. View the manuscript online here, at the Cambridge University Digital Library. In the library catalogue, the Psalter is referred to as “C.9 Psalter (Irish)”. You can read the library catalogue entry here.

A Psalter is a volume that includes the Book of Psalms from the Christian Old Testament, as well as other devotional material. A psalm is a religious verse which is recited or sung in Christian and Jewish worship.

Manuscripts may have a title, like the Southampton Psalter, but scholars also refer to them using the shelf on which they are kept. The Southampton Psalter’s catalogue reference is C.9. The reference C.9 tells us that the Southampton Psalter is the ninth manuscript on shelf C in St John’s College.

After seeing the manuscript, what are your initial reactions?

Make a mind map of possible research questions.

These could ask anything about the manuscript that sparks your interest.

The illustrations

The context

The audience

The materials used to make it

The psalms in psalters were often richly decorated, not just in Ireland and England but across the Christian world.

Religious texts were just one genre of writings found in medieval manuscripts. Manuscripts contain a huge variety of content, from stories and poems to medicine and mathematics. Don’t feel you need to stick to psalters in your research!

British Library MS Add. 10289 A thirteenth-century compilation of tales, moralistic and religious texts, and medical recipes from France.

Cambridge University Library MS Dd.10.68 A Hebrew book of medicine from fifteenth-century Italy.

Cambridge University Library MS Add.3139 A seventeenth-century book of Persian poetry.

Walters MS W.73 A science textbook for monks from twelfth-century England.

Walters MS W.593 A version of the Wonders of Creation from sixteenth-century Turkey.

Or you might like to look at a psalter from the eleventh-century eastern Mediterranean, from thirteenth-century Germany, or from eighteenth-/nineteenth-century Ethiopia. Do you notice any similarities with the Southampton Psalter?

With such a long history, there are many different strands of research that could be followed.

Spend five minutes looking through the Southampton Psalter.

Think about what you would like to investigate. Which aspect of the manuscript interests you most? What questions do you want to ask?

Using resources

So far, we have looked at two resources: the manuscript, which is a primary source; and a video, which is a secondary source.

Primary sources

Primary sources are at the core of research, since they provide direct evidence from a particular time period. Primary sources can include a first-hand account of events, a letter, a manuscript, or another historical artefact. Our primary source for this project is the Southampton Psalter itself.

Secondary sources

Secondary sources – such as articles, books, and websites – are based on primary sources. They are not direct evidence, but they can help you interpret and understand a primary source.

It is important to distinguish how reliable a source is. What indicators of reliability can you think of?

- Who is the target audience, and what is the author’s bias? For example, an academic publication on symbolism in Irish manuscripts will be more reliable than a website trying to sell you Celtic jewellery.

- Is the author qualified? For example, does the author have a degree or similar experience in that subject?

- Does the author back up their arguments with reference to other sources?

We can apply similar questions to both primary and secondary sources:

- What is the bias or agenda of the author (or the person who created the source?)

- In what context (social, political, historical) was the source produced?

- How reliable is it? Can we find other sources to confirm its reliability?

2. Starting Your Project

We decided to find out more about the different uses that this manuscript has had over its 1000 year lifespan.

Our first step was to understand what is already known about the Psalter.

We looked at a secondary source, a catalogue that was written about the manuscripts in St John's College.

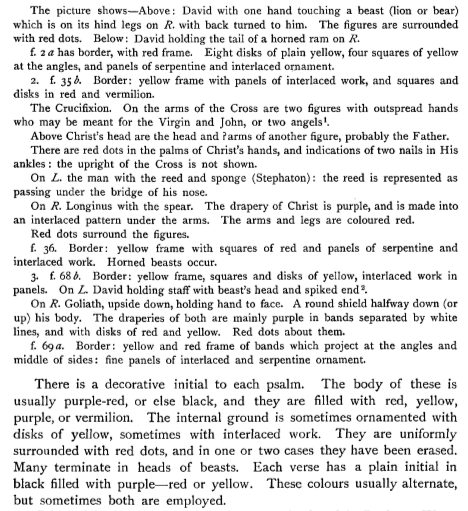

The manuscript catalogue for St John’s College Cambridge was written in 1913 by M. R. James. Spend two minutes reading the description of the decoration in the Southampton Psalter in the manuscript catalogue – don’t worry if there are any words you don’t understand! Technical terms are often used in manuscript catalogues; we will come across some of these terms in our research.

What can you find out about the Psalter from the entry below?

Manuscript catalogues are the first source that should be consulted when researching a manuscript. They contain descriptions of the origin, date, appearance, and content of a manuscript. We can use them to navigate the manuscript and to identify which questions need research.

We also looked at other research done on the manuscript by scholars. Pádraig Ó Néill has written an article in which he looks at the ‘lives’ of the Southampton Psalter and identifies two key stages: as a book for medieval Irish scholars, and as a prized item of antiquity in England. See Further Reading for details of Ó Néill’s article.

You can listen to a recording of his lecture on the Southampton Psalter at St John’s College here.

Inspired by Ó Néill’s description of the ‘lives’ of the Southampton Psalter, we will look at each of the ‘lives’ and discover more about the Southampton Psalter’s journey from medieval Ireland to its home in Cambridge today. This will give us an overview of the whole history of the Southampton Psalter.

3. Illustration & Iconography

Important medieval manuscripts were sometimes illuminated with vivid decoration, in order to be used as display books in monasteries. Display books were used by monks and nuns to read out the Bible in chapels and churches (in other words, they were on display!). Illumination is the use of colours to decorate a manuscript, such as full-page images and highlighted letter initials.

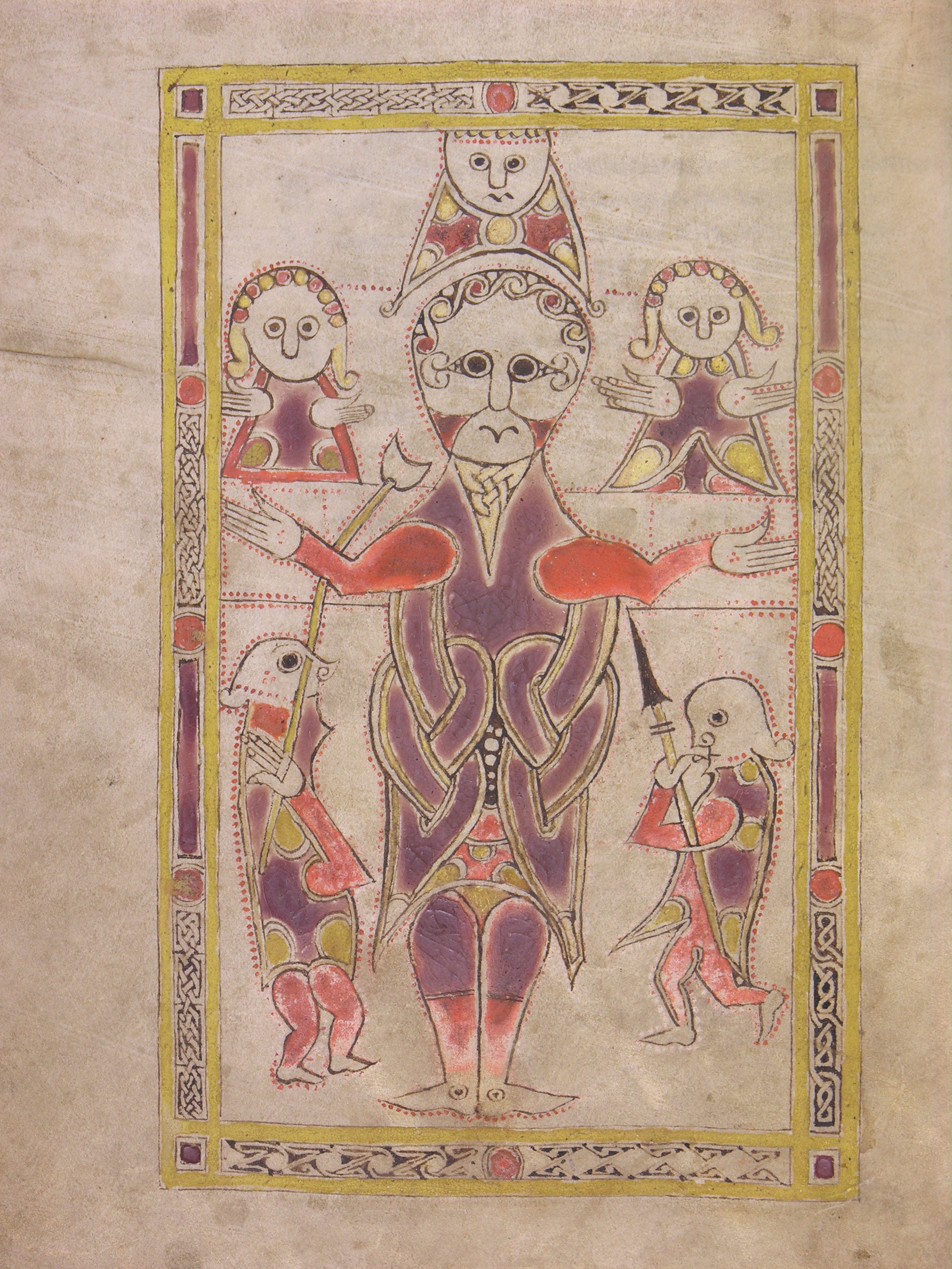

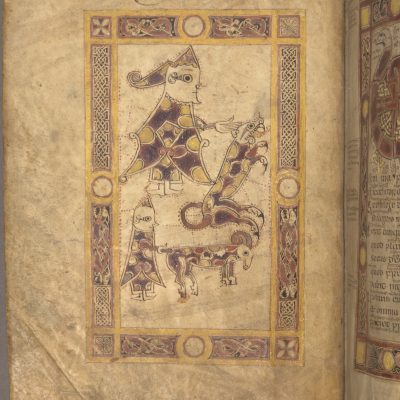

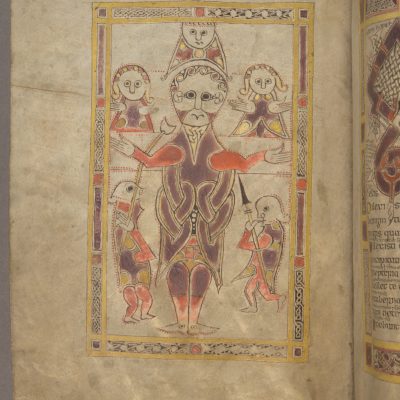

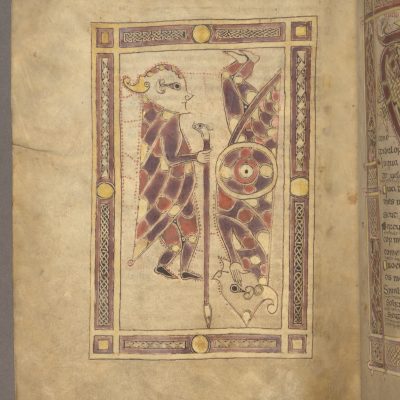

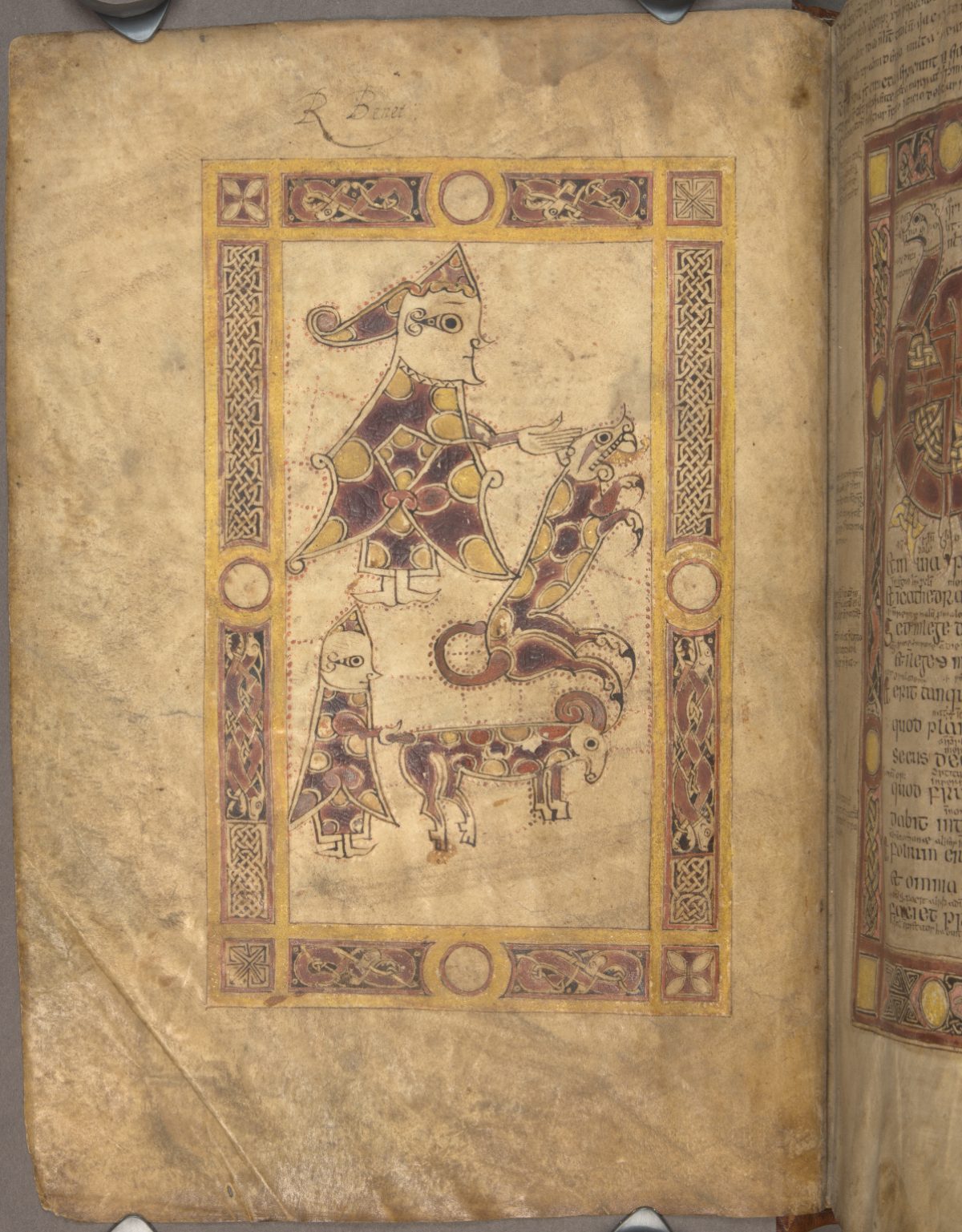

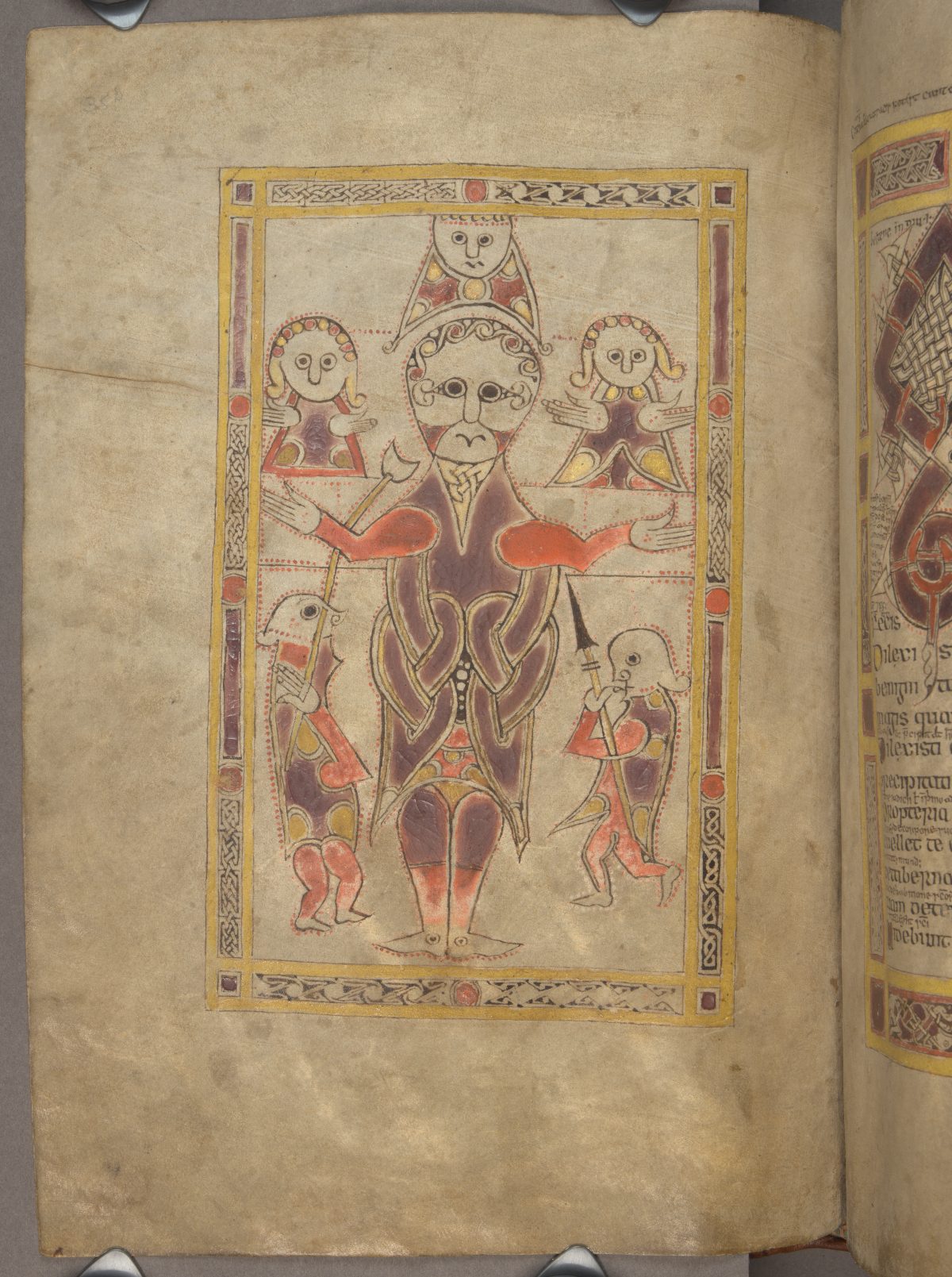

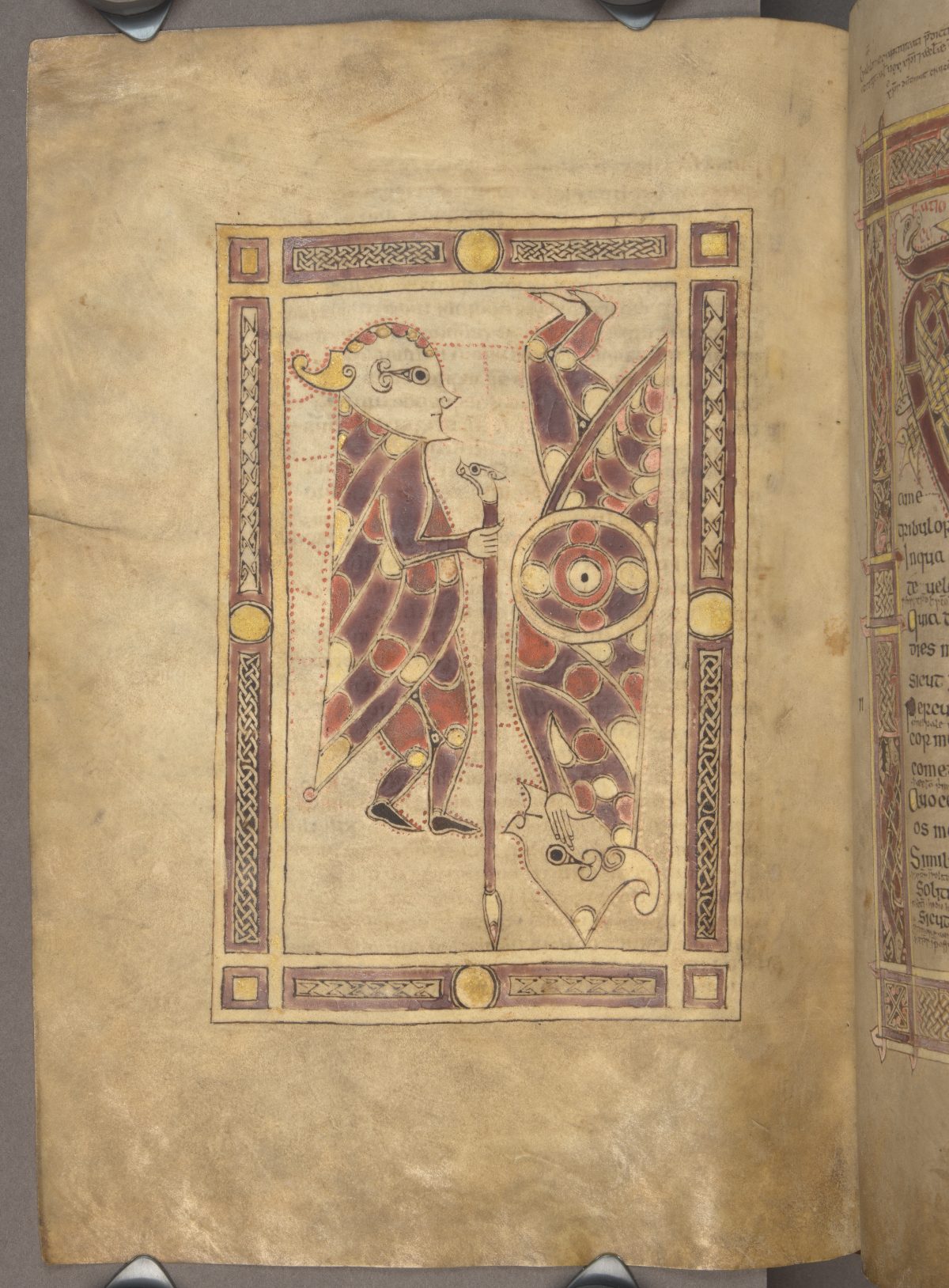

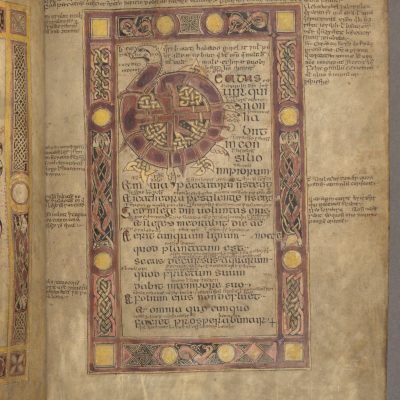

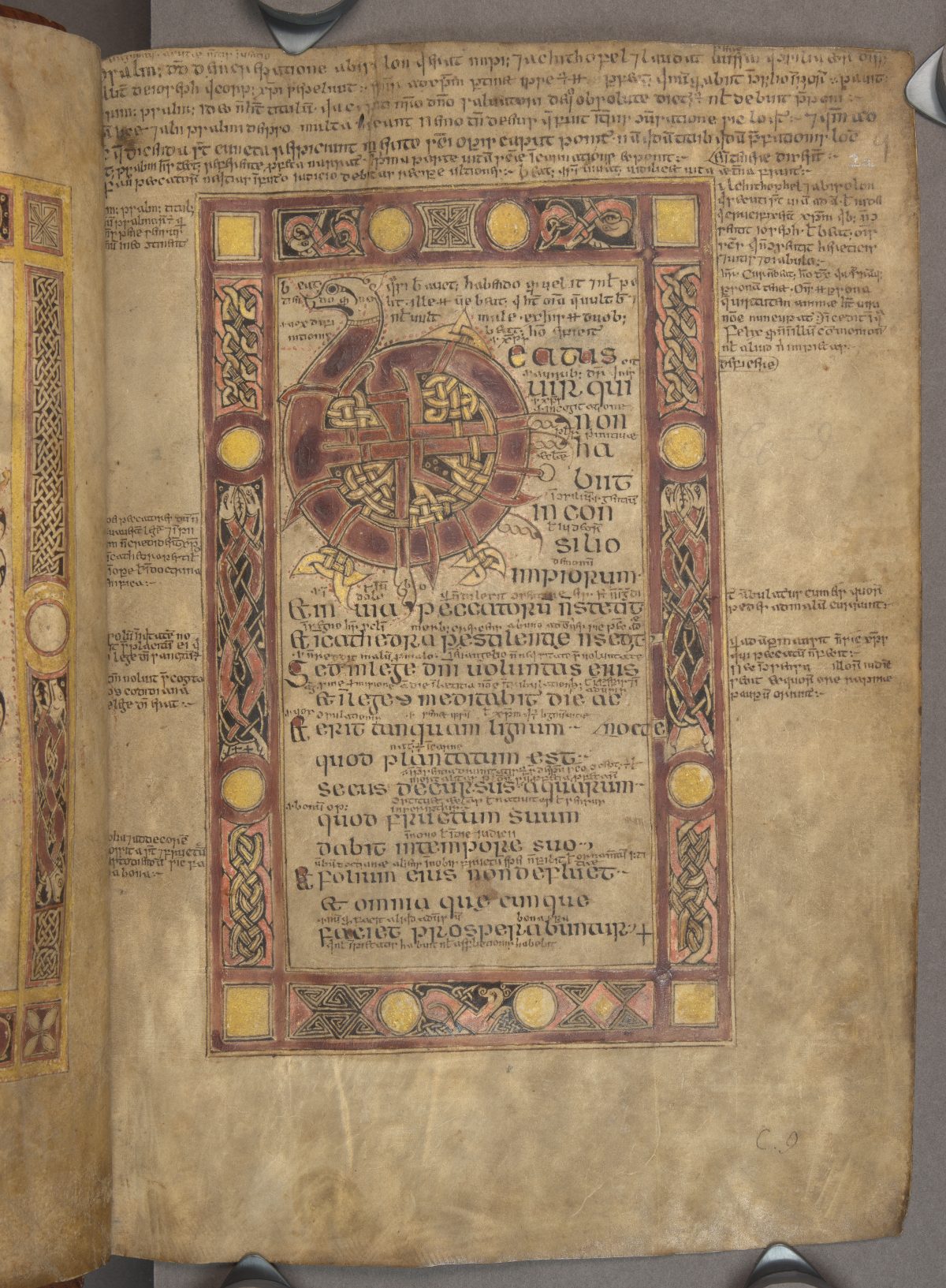

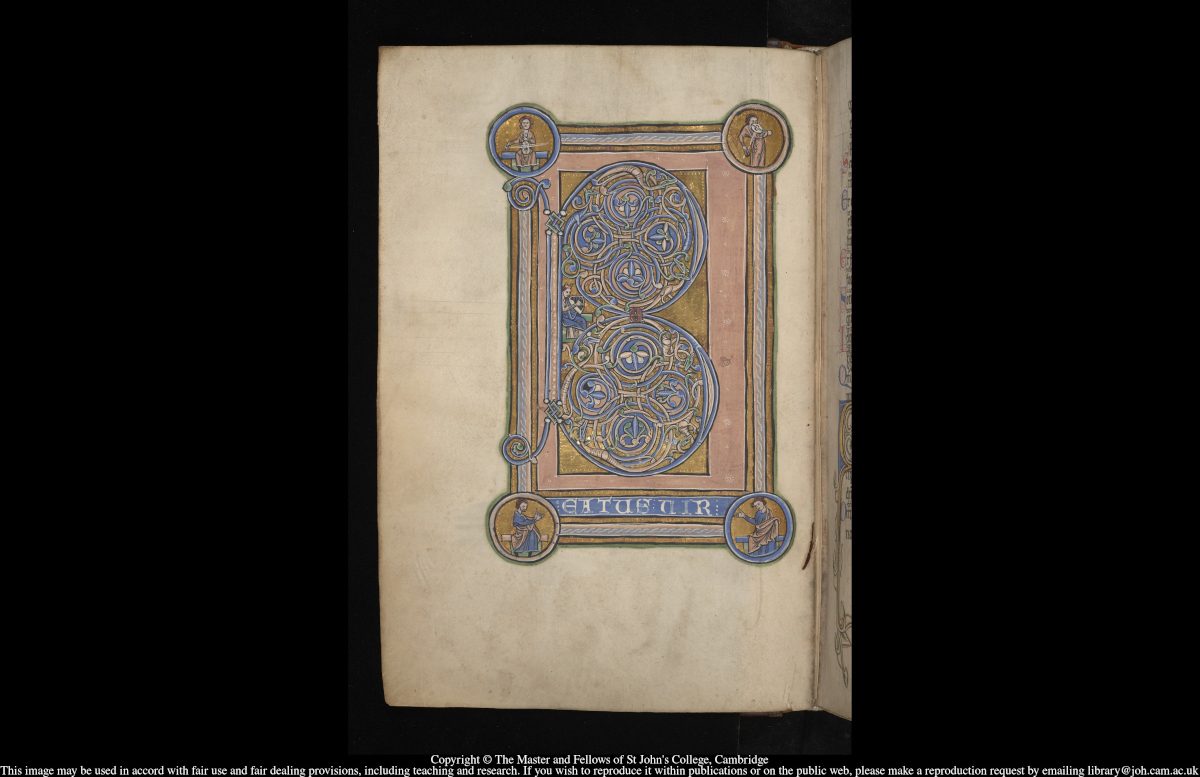

The Southampton Psalter contains three full-page miniatures. A miniature is an illustration in a manuscript which is separate from the text. (Despite their name, miniatures don’t necessarily have to be small – the Southampton Psalter miniatures fill the whole page!)

We started our project by looking at the miniatures.

Spend two minutes looking at the miniatures in the Southampton Psalter.

What are your first impressions?

Pick one miniature to study more closely. Spend five minutes looking carefully at it.

What questions might you ask about the miniature?

See if your questions are answered in the videos below.

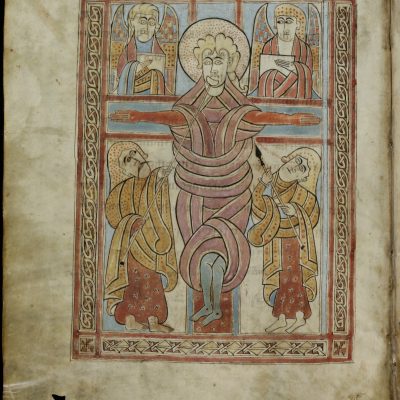

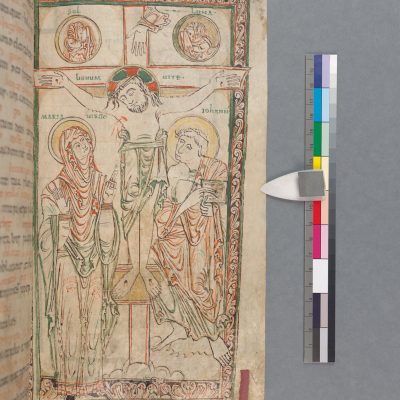

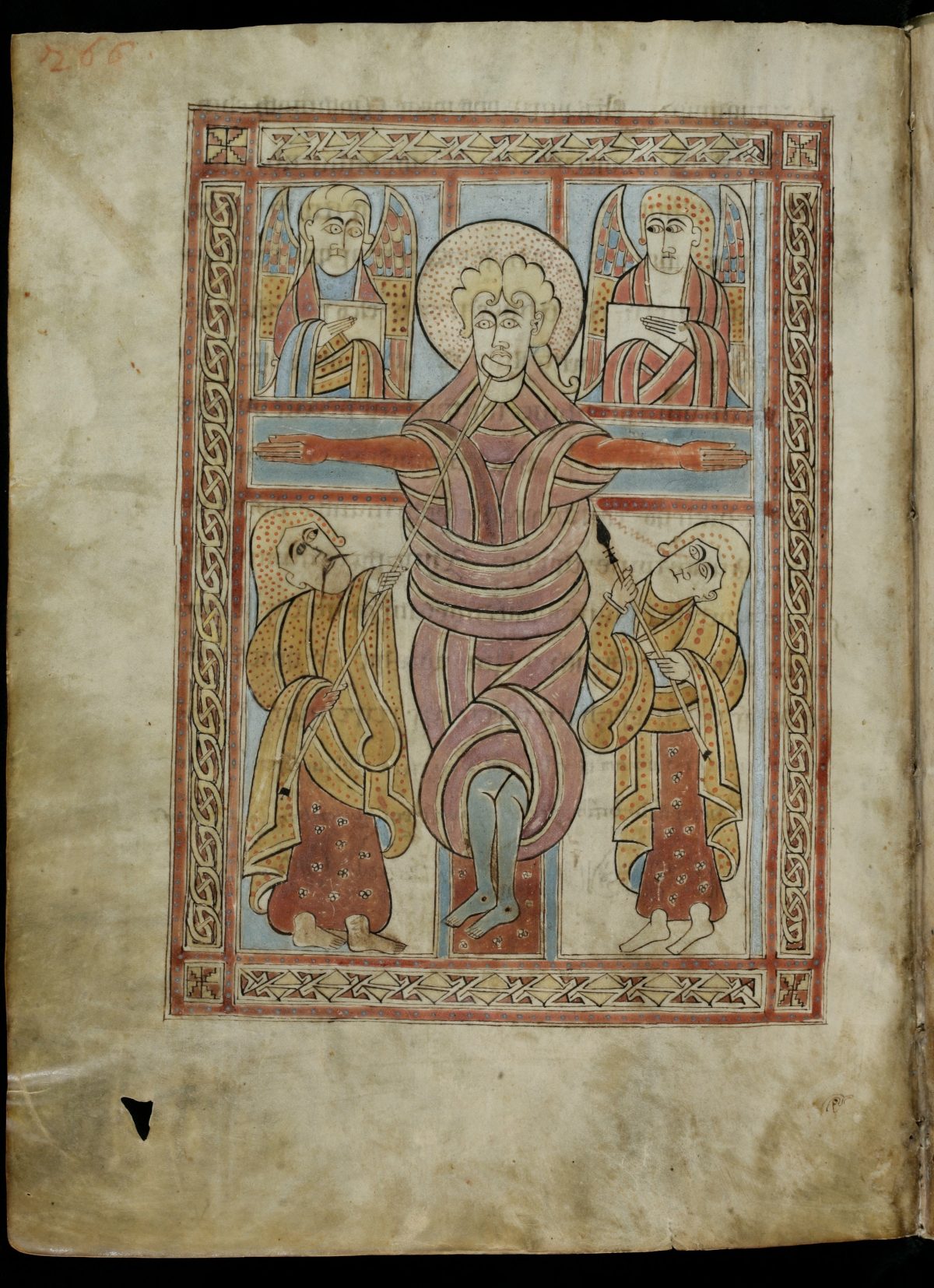

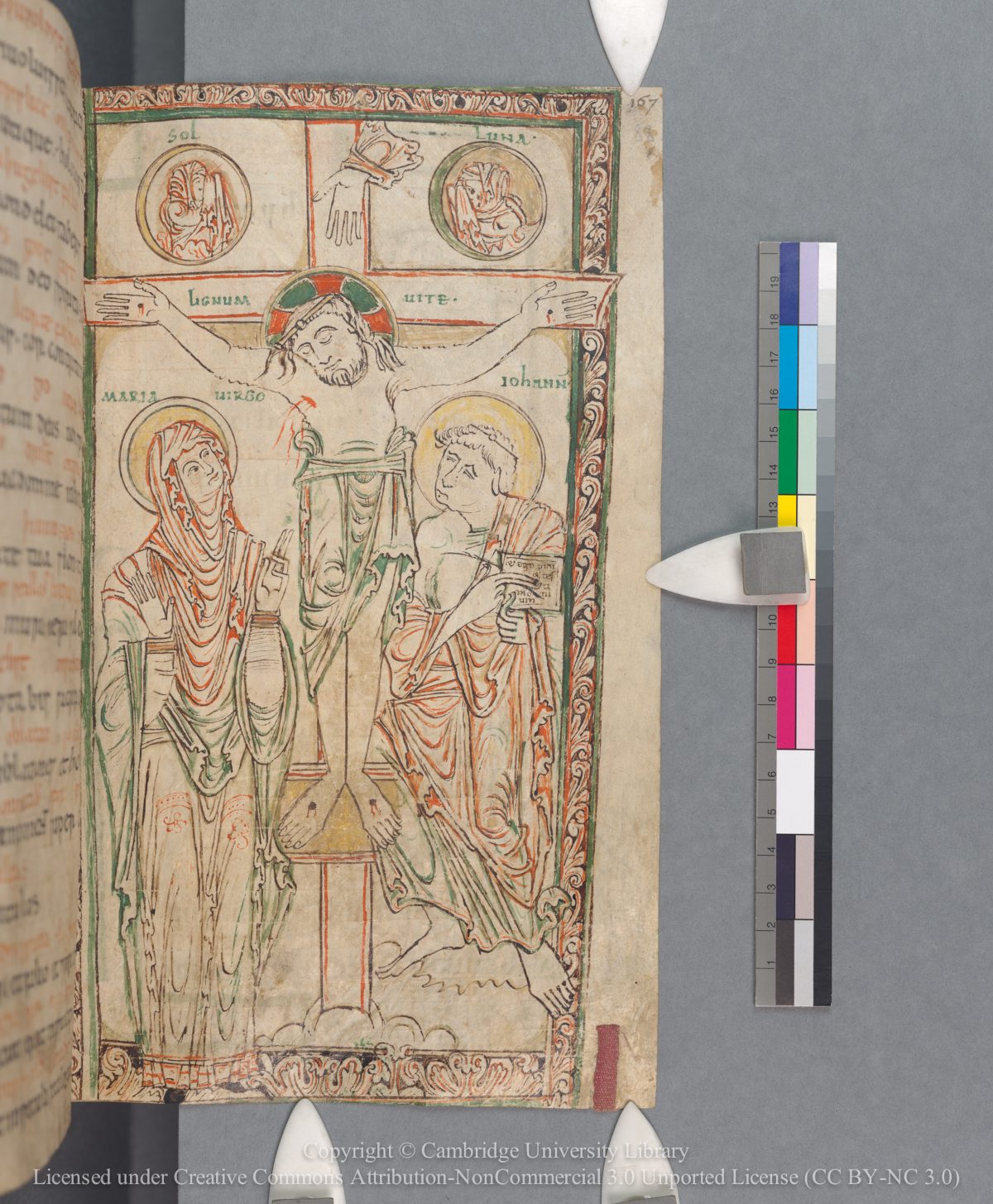

We chose to compare the Crucifixion miniature with other miniatures from a similar date which featured the same subject, in order to find out how typical the Southampton Psalter is. We chose a miniature from the St Gall Gospels (eighth-century, written by Irish scholars) and the Winchcombe Psalter (eleventh-century, written in England). Like psalters, gospels are religious texts: the gospels are the first four books of the New Testament in the Bible, which recorded the life of Christ. We looked for similarities and differences between the miniatures.

How are the figures dressed?

Do all three use the same figures?

Is the placement of the figures the same in the three miniatures?

How realistic are the miniatures? Did the illuminators intend them to be realistic?

An illuminator is an artist who decorates a manuscript using colour.

J. A. Herbert, Deputy Keeper of Manuscripts in the British Library in the early 20th century, described the miniatures in the Southampton Psalter as ‘crude and barbaric’. (Illuminated Manuscripts, 1911)

Françoise Henry, an art historian in the mid-twentieth century, had a different opinion: ‘What is lost in expression and monumentality is regained in decorative effect and in the enchanting, enamel-like brilliance of the patchwork covering the figures’. (Remarks on the Decoration of Three Irish Psalters, 1960/61)

With which of these descriptions do you most agree and why?

‘Scholarship’ refers to research by academics, such as books, articles, and lectures.

When engaging with scholarship, it is important also to think carefully about your source. In this case, could there be another explanation for the simplicity of style? For example, might the miniature be unfinished?

We also noticed the decorative style of the miniatures. The Southampton Psalter and the St Gall Gospels both use bold, intricate ribbon-like patterns, while the Winchcombe Psalter uses delicate, flowing penmanship.

Modern scholars have identified the ribbon-like pattern in the Crucifixion miniature with medieval Ireland, and we see this pattern in both the Southampton Psalter and the St Gall Gospels.

Colours and symbolism

We were particularly interested by the colour palette used to show the Crucifixion. Producing colour was expensive, and the illuminator would have thought carefully before decorating a miniature.

Look again at the miniatures, and make a note of what colours the illuminators used.

How do the colours of the Southampton Psalter miniature compare to the St Gall Gospels and the Winchcombe Psalter miniatures?

We decided to look closely at the colour of the bodies and tunics in the Southampton Psalter and the St Gall Gospels. You might prefer to investigate the different palette used in the Winchcombe Psalter.

We did some secondary reading and discovered that red could be used to signify Christ’s wounds. In this miniature, red represents the blood of Christ. Red covers the arms and legs of Christ (the central figure in each miniature), as well as those standing directly next to him.

Why did the illuminator use red for the body of Christ and the bodies of those standing next to him?

Was the illuminator conveying a message about the Crucifixion?

You might like to find out more about colour symbolism in illuminated medieval manuscripts. Follow this link to the Fitzwilliam Museum’s resource The Art and Science of Illuminated Manuscripts.

Compare the figures and their tunics in the Southampton Psalter and the St Gall Gospels miniatures.

What do you notice?

In both manuscripts, Christ’s tunic is purple. In the Southampton Psalter, the figures beside Christ also wear purple tunics; in the St Gall Gospels, the figures wear dark yellow tunics.

Purple typically symbolises great wealth or status.

In the Southampton Psalter, the illuminator has applied purple – and the significance of the colour purple – to Christ and the soldiers.

What can this tell us about how the illuminator interpreted events of the Crucifixion? Should we be surprised that the illuminator represents Christ and the soldiers in this way?

Conclusions

Illuminated manuscripts like the Southampton Psalter would probably have been used, in their first 'life', as high-prestige display books in monasteries. These were books used by monks and nuns to read out the Bible in chapels and churches.

By examining the colours, images, and styles of the miniatures in the Southampton Psalter, we have established that it was an expensive and time-consuming manuscript to produce. The colours and layout of the Crucifixion have some similarities with other European religious manuscripts, but also some differences. The style of decoration points to its origin in Ireland, and the illuminator shows an interest in interpreting the biblical scenes he illustrated.

Illuminations like those in the Southampton Psalter direct the viewer to contemplate the meaning of the Crucifixion. Why do you think the artist of the Southampton Psalter chose this colour palette and style of artistry to portray the Crucifixion? What meanings did they want the reader to think about?

4. A Scholar's Textbook

Decoration is just one aspect of a manuscript. Writing is another. You might like to start your own project with this ‘second life’.The study of written characters – or ‘scripts’ – is known as palaeography. 'Palaeography' is the study of the history of scripts, including punctuation, in medieval manuscripts. Those who wrote in medieval manuscripts are called ‘scribes’. We turned to the scripts used in the Southampton Psalter.

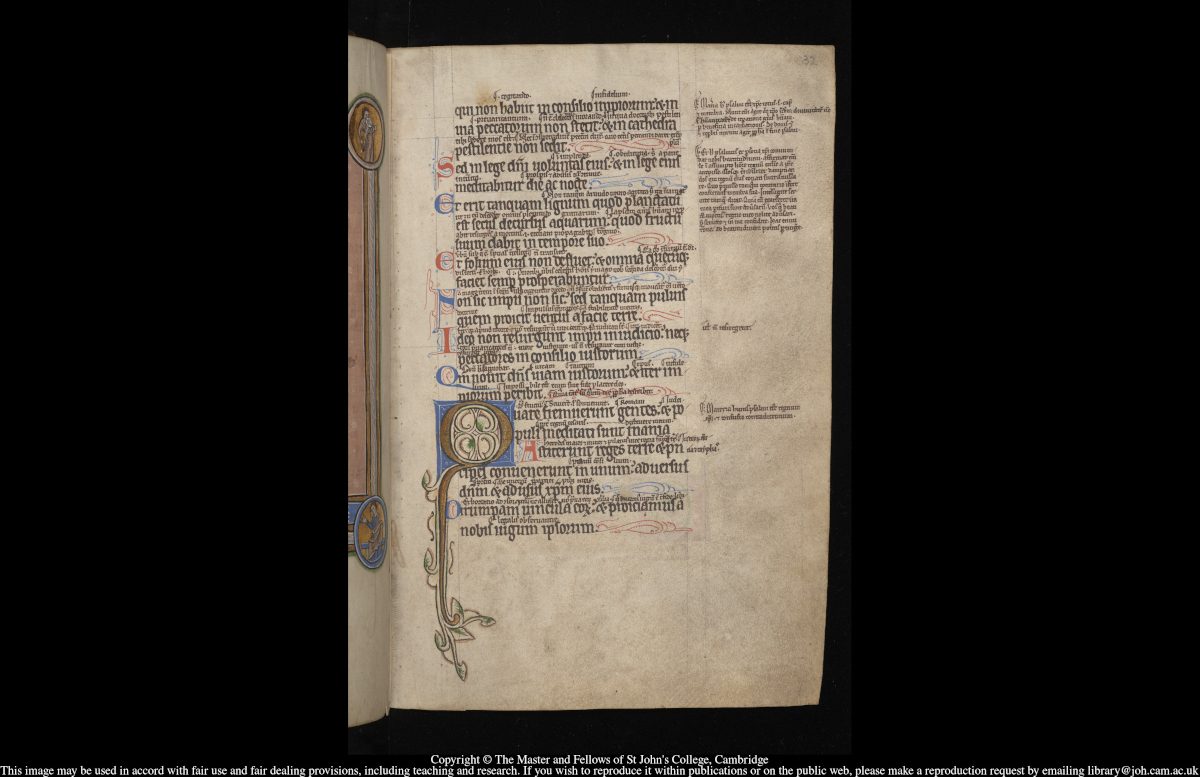

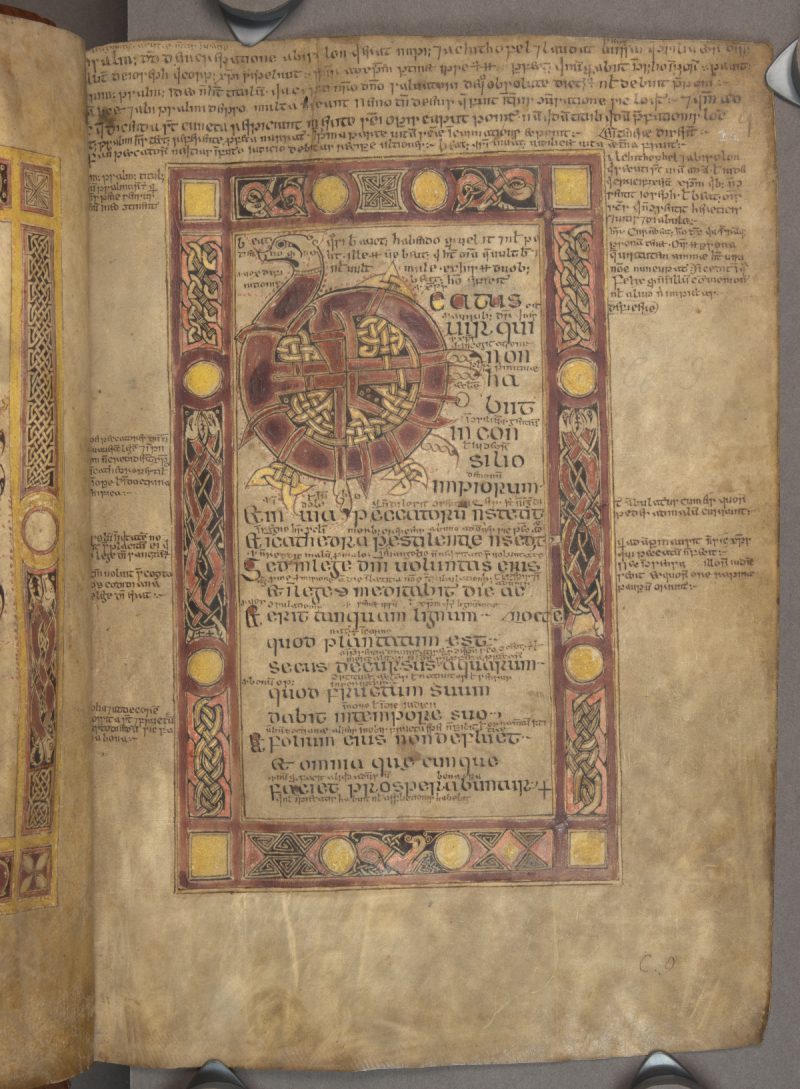

We decided to look at Psalm 1, to see what it can tell us about the audience of this manuscript.

Discover what the script of Psalm 1 of the Psalter says below.

Beatus vir qui non habiit in consilio impiorum, et in via peccatoruum non stetit, et in cathedra pestilentiae non sedit;

Sed in lege Domini voluntas eius, et in lege eius meditabitur die ac nocte.

Et erit tanquam lignum quod plantatum est secus decursus aquarum, quod fructum suum dabit in tempore suo et folium eius non defluet; et omnia quaecunque faciet prosperabuntur.

Non sic impii non sic; sed tanquam pulvis quem proiecit ventus a facie terrae.

Ideo non resurgent impii in iudicio, neque peccatores in consilio iustorum;

Quoniam novit Dominus viam iustorum et iter impiorum peribit.

Blessed is the one who does not walk in step with the wicked or stand in the way that sinners take or sit in the company of mockers,

But whose delight is in the law of the Lord, and who meditates on his law day and night.

That person is like a tree planted by streams of water, which yields its fruit in season and whose leaf does not wither – whatever they do prospers.

Not so the wicked. They are like chaff that the wind blows away.

Therefore the wicked will not stand in the judgement, nor sinners in the assembly of the righteous.

For the Lord watches over the way of the righteous, but the way of the wicked leads to destruction.

Even though we might not always understand the language or content of a manuscript, very often the layout will provide information.

Spend five minutes looking at Psalm 1.

Think about the following questions:

How many different sizes and styles of script can you identify?

Where have different sized scripts been placed on the page?

Can the size and position of the different scripts tell us about how this manuscript was being used?

Can you locate the first word of the psalm?

Southampton Psalter, f.2r, Copyright St John’s College, Cambridge

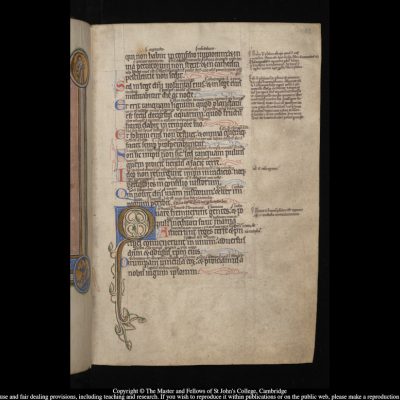

The layout, script, and glossing of a manuscript can reveal its intended audience. ‘Glossing’ refers to the annotation of texts in manuscripts. This includes notes written directly on the page (either between the lines or in the margins) and longer, interpretative commentary. We know that the main content of the Southampton Psalter is the psalms, written in Latin. Other comments have been added around the psalms, some in Latin and some in Irish.

Our first observation was the sheer quantity of writing on the page. How can we make sense of it all? Watch this video to find out more.

Not all glossing was reserved for serious scholarly output. Sometimes scribes recorded their thoughts and feelings. Here the scribe has expressed his feelings in Irish and Latin.

On the left, we find text in Irish: beltene inndiu .i. for cetain (‘It is May Day today, that is Wednesday’).

On the right, we find text in Latin: misere nobis Domine misere nobis (‘Have mercy on us, Lord, have mercy on us’).

Did you notice that some of the letters are missing? The scribe has actually written beltene īndiu .i. f– cēt– mis– nob– d–ne mis– nob–. The lines you see above the words tell you that they have missed some of the letters out (known as ‘suspension strokes’). Scribes were the photocopiers of their day and dropping some letters of common words saved ink and saved time (rather like text-speak today!).

By looking at the size and style of script surrounding the text of the psalms, we have learned that the Southampton Psalter was used by Irish scholars (perhaps students?) to interpret and reflect on the meaning of the psalms.

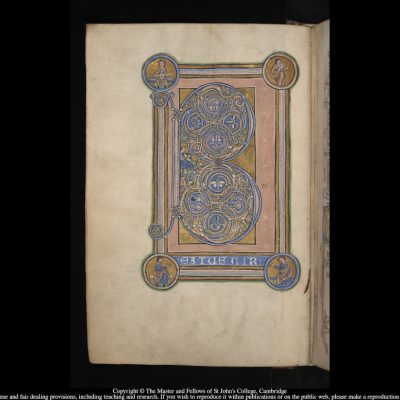

We turned to another contemporary psalter for comparison, to find out if it is common for illuminated psalters to be annotated like a textbook. We chose the Psalter of Robert de Lindsey. This psalter and the Southampton Psalter were both donated to St John’s College by the Earl of Southampton. In the manuscript catalogue, the Psalter of Robert de Lindsey is known as D.6. It is a thirteenth-century English manuscript containing different religious material, including a psalter, in Latin.

Spend a few minutes looking carefully at Psalm 1 in the Southampton Psalter and in the Psalter of Robert de Lindsey.

What similarities and differences do you notice?

The style and colour-scheme are different, but both psalters are highly decorative; the Psalter of Robert de Lindsey has an entire page for the letter B. Both psalters have glossing written in between lines and in the margins.

This tells us that even though these two psalters were produced in different countries, the method of setting out the page is the same: the text of the psalm in the middle; decorative capitals to mark the start of each line of the psalm; and space left in the margins for scholars to discuss the meaning of the psalm.

Conclusions

While we may not be familiar with the languages used in the Southampton Psalter, we have been able to find out much by looking at the layout of the opening page of the psalms. We have discovered that it was no longer just a display book. It was also a space for scholars to discuss and interpret the psalms.

5. Lords & Libraries

So far we have looked at two elements of the first 'life' of the Southampton Psalter: as a high-status display book in medieval Ireland, and as a textbook for medieval Irish scholars. So why is it known as the Southampton Psalter, and how did it end up in St John’s College Cambridge?

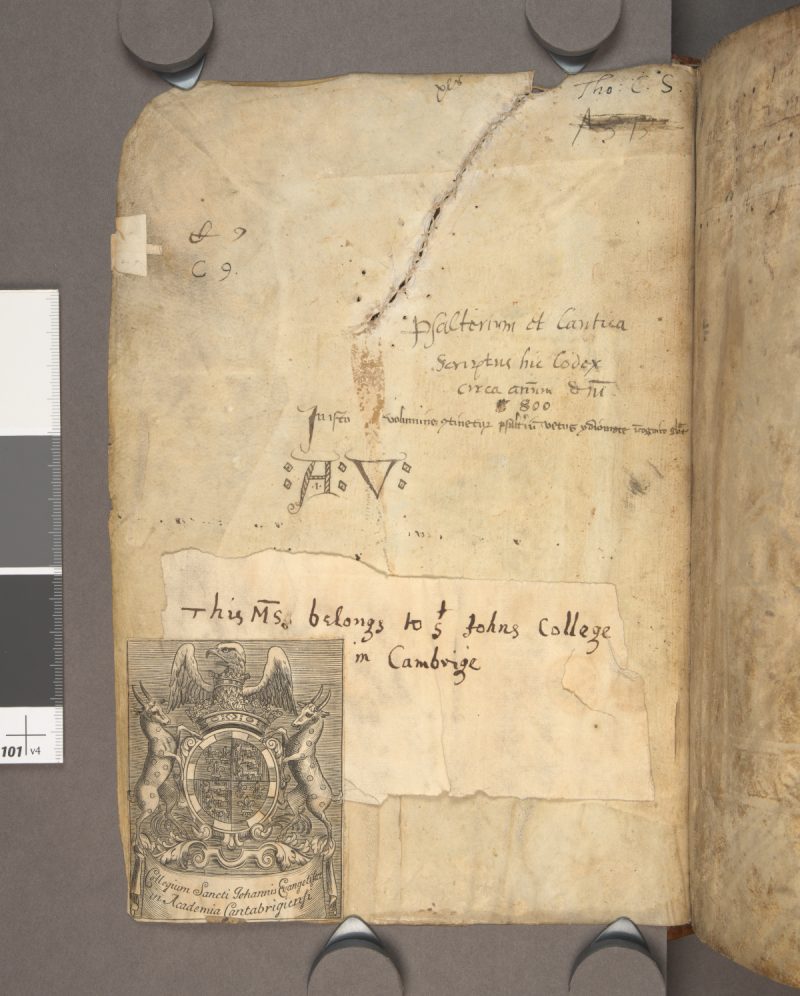

The inside front cover of a manuscript can often reveal clues as to its history. Owners of manuscripts sometimes autographed the beginning of a manuscript (just as we might write our name in a book today).

Spend a few minutes looking at the inside front cover of the Southampton Psalter. What can you see?

The inside cover of the Southampton Psalter.

Southampton Psalter, f.(i)v. Copyright St John’s College, Cambridge

There are several notes written in a variety of sizes and scripts. On the bottom half of the page is the St John’s College bookplate, showing the College’s coat of arms. This is the most recent addition to the page. Find out more in this video.

From our secondary reading of Pádraig Ó Néill’s article, we learned that the notes in the middle of this page were the work of a medieval librarian called John Whytefield. Whytefield worked in St Martin’s Priory in Dover. In 1389 Whytefield made a catalogue of manuscripts in the priory library. The letter A on this page tells us that the Southampton Psalter occupied an important position in the priory library. During the Reformation the Southampton Psalter disappeared from the records (presumably sold off from St Martin’s Priory to a private collector) before resurfacing in the possession of William Crashaw.

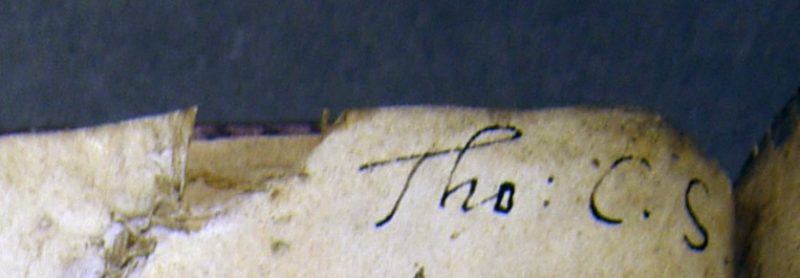

Look carefully at the autograph in the top right of the inside front cover. What might the letters signify?

We thought that these letters may have belonged to a previous owner.

To find out more, we contacted the Library at St John’s College. In the College Archives, we found letters to the Master of St John’s College from a man called William Crashaw, from between 1614 and 1618, discussing the donation of books to the College.

We wanted to find out who William Crashaw was, and his connection to St John’s. Read this description of Crashaw. Why did Crashaw sell his collection to the Earl of Southampton?

Patronage was a key role of an individual of high status. It was a way of investing in the future – either in intellectual pursuits, such as libraries, or more popular pursuits such as plays – and showing off your wealth at the same time.

After the Earl of Southampton’s death in 1624, the collection was delivered to the St John’s Library between 1626 and 1635 by his late wife and son. We know this thanks to another letter in the College archives. His wife was called Elizabeth Vernon, and his son was called Thomas, the fourth Earl of Southampton.

We can now identify the autograph on the top-right of the front inside cover of the Southampton Psalter manuscript. Tho: C.S. stands for Thomas Comes Southampton (‘comes’ means Earl in Latin). The third Earl’s son Thomas must have signed the manuscript, even though he knew his father had promised it to St John’s College!

Conclusions

Using the inside front cover of the manuscript as a starting point, we have established that the Southampton Psalter was a valued item of antiquity by 1389. By 1615, it was in the hands of the third Earl of Southampton. It was no longer a working scholar’s book, but a treasured witness of the past.

6. Where Next?

Our research into the Southampton Psalter has demonstrated three very different ‘lives’: firstly, as a lavishly decorated display book; then as a learning resource for scholars; and finally as a valued object of antiquity, preserved by a series of bibliophiles, without whom the Southampton Psalter would have been lost to the damages of time. A bibliophile is someone who collects and has great interest in books.

As we have seen, manuscripts are not static: they are living, evolving documents which take on the imprint of their time. So what’s next for the Southampton Psalter?

The future of manuscript studies

Manuscripts are very susceptible to damage from temperature, humidity, and the wear and tear of ageing. Conservation can protect manuscripts.

Explore the Fitzwilliam Museum’s resource on manuscript conservation.

Digitisation is the process of converting information into a digital format. In the case of manuscripts, this involves converting images of manuscripts into a format which can be stored and accessed electronically. This allows researchers to access high-resolution images of manuscript pages without affecting the manuscript itself. Digitisation also allows manuscripts to be viewed from anywhere in the world.

Digitisation of manuscripts is becoming increasingly popular. In developing this resource, we digitised the Southampton Psalter, making it available to view online for the first time. The images you have been using were made possible by the digitisation process.

Read this short blog from Cambridge University Library Collections on manuscript digitisation.

What are the benefits of digitisation? Are there any disadvantages to digitisation?

Many academic institutions are digitising their manuscripts and sharing them online. Manuscripts cover a huge variety of subjects from across the world. For your project, you might like to look at the wide range of manuscripts available online from these institutions:

British Library Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts

Fitzwilliam Museum ILLUMINATED: Manuscripts in the making

Irish Script on Screen Project

To find out more about manuscript binding, have a look at these online resources:

Department of Anglo-Saxon, Norse & Celtic Palaeography and Codicology resources

Princeton University Library Hand Bookbindings

British Library Database of Bookbindings

Scholars are starting to turn to scientific, non-invasive technology to find out the secrets of a manuscript’s history. In this context, ‘non-invasive’ refers to any scientific method which causes zero damage or interference to the physical manuscript such as microscopy, infra-red imaging, and spectroscopic analysis.

Watch these short videos from the MINIARE project and William Noel’s TED Talk on non-invasive analysis and its potential for manuscripts. What can these scientific analyses of manuscripts reveal? What might they tell us about the Southampton Psalter?

Ideas for practical projects

For a more hands-on project, you might like to try the following:

Make your own miniature using the methods and styles of medieval scribes. This could include making your own pigments for colour, provided it is safe to do so. Which themes were common in medieval miniatures? Which colour scheme will you use? Why? To start, watch this video on making miniatures and this video on pigments from the British Library.

Try writing in the same style as one of the scripts used in the Southampton Psalter (or another manuscript of your choice). Think about how and why medieval scribes copied texts. What text will you copy? How will you lay out the page? Why?

Recreate a medieval library by putting together a list of medieval manuscripts. Have a look at the Durham Priory Library Recreated and Medieval Libraries of Great Britain projects for a starting-point. In which genres of books were medieval librarians interested? What was the purpose of a medieval library? Who might have used such a library?

7. Further Reading

It is important to cite the sources that you use in your research (this is known as a ‘bibliography’). Here are some of the sources we used during our project, as well as some ideas for further research on manuscripts.

Illustration & Iconography

The Southampton Psalter (Cambridge, St John’s College MS C.9)

The Psalter of Robert de Lindsey (Cambridge, St John’s College, MS D.6 ff. 72–3)

The St Gall Gospels (St Gallen, Stiftsbibliothek, Cod. Sang. 51 p. 266)

The Winchcombe Psalter (Cambridge University Library, MS Ff.1.23 f. 88r)

Ó Néill, P., ‘Psalterium Suthantoniense’, Corpus Christianorum Continuatio Mediaevalis 240 (Turnhout, 2012)

Duncan, E., ‘‘The Southampton Psalter’: a Palaeographical and Codicological Exploration’, Anglo-Saxon, Norse & Celtic Manuscript Studies 4 (Cambridge, 2004)

Henry, F., ‘A Century of Irish Illumination (1070–1170), Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Archaeology, Culture, History, Literature 62 (1961–63), 101–66

Henry, F., ‘Remarks on the Decoration of Three Irish Psalters’, Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Archaeology, Culture, History, Literature 61 (1960/1961), pp. 23–40

Herbert, J. A., Illuminated Manuscripts (London, 1912)

Fitzwilliam Museum: COLOUR: The Art and Science of Illuminated Manuscripts

James, M. R., A Descriptive Catalogue of the Manuscripts in the Library of St John’s College Cambridge (1913, pp. 76–8) (Southampton Psalter (C.9) description here)

McNamara, M., ‘Five Irish psalter texts’, Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Archaeology, Culture, History, Literature 109C (2009), 37–104

McNamara, M., and Sheehy, M., ‘Psalter Text and Psalter Study in the Early Irish Church (A.D. 600–1200), Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Archaeology, Culture, History, Literature 73 (1973), 201–98

Ní Ghrádaigh, J., ‘Audience, visuality and naturalism: depicting the Crucifixion in tenth-century Irish art’, in The mystery of Christ in the fathers of the Church, ed. J. E. Rutherford and D. Woods (Dublin, 2012)

Ní Ghrádaigh, J., ‘Towards an emotive Christ? Changing depictions of the crucifixion on the Irish high cross’ in Envisioning Christ on the Cross: Ireland and the Early Medieval West, ed. J. Mullins, J. Ní Ghrádaigh, and R. Hawtree (Dublin, 2013), pp. 262–85

O’Reilly, J., ‘Early Medieval Text and Image: the Wounded and Exalted Christ’, Peritia 6–7 (1987–88), 72–118

O’Reilly, J., ‘Seeing the crucified Christ: image and meaning in early Irish manuscript art’, in Envisioning Christ on the Cross: Ireland and the Early Medieval West, ed. J. Mullins, J. Ní Ghrádaigh, and R. Hawtree (Dublin, 2013), pp. 52–82

Online resources on illuminated medieval manuscripts:

A Scholar’s Textbook

To find out more about abbreviations used in medieval Irish manuscripts, explore the Tionscadal na Nod online resource.

Tracing the history and development of ideas in glossing is fascinating but complicated work. If you would like to find out more about the scribes who wrote the Southampton Psalter, start off by reading the following:

Duncan, E., ‘The Southampton Psalter: a Palaeographical and Codicological Exploration’, Anglo-Saxon, Norse & Celtic Manuscript Studies 4 (Cambridge 2004)

Ó Néill, P., ‘Psalterium Suthantoniense’, Corpus Christianorum Continuatio Mediaevalis 240 (Turnhout, 2012)

Ó Néill, P., ‘Some Remarks on the Edition of the Southampton Psalter Irish Glosses in Thesaurus Palaeohibernicus, with Further Addenda and Corrigenda’, Ériu 44 (1993), 99–103

Lords & Libraries

St John’s College Archives SJAR/6/2/2/1 (letters from William Crashaw)

Herbert, M., de Brún, P., Catalogue of Irish manuscripts in Cambridge libraries (Cambridge, 1986)

James, M. R., The Ancient Libraries of Canterbury and Dover (Cambridge, 1903)

Ó Néill, P., ‘An Irish Psalter with Two Lives: the Story of the Southampton Psalter’, in From Medieval to Modern: Aspects of the Western Literary Tradition, ed. Y. Wada (Kansai, 2017), pp. 1–37

St John’s College Cambridge: History of the Old Library (online here)

St John’s College Cambridge: William Crashaw’s Library (online here)

Wallis, P. J., ‘The Library of William Crashawe’, Transactions of the Cambridge Bibliographical Society 2 (3) (1956), 213–28

If you would like to find out more about the Psalter of Robert de Lindsey, have a look at the catalogue entry here. Remember that the Psalter of Robert de Lindsey is referred to as D.6 in the catalogue.

Credits

Produced by St John's College and St John's College Library, in collaboration with staff at the Fitzwilliam Museum.

Written by Dr Alice Taylor-Griffiths, in association with Prof. Máire Ní Mhaonaigh and Dr Rebecca Shercliff, all of the Department of Anglo-Saxon, Norse, and Celtic, and St John’s College.

Video and Photography: Dr Ian McKee

With thanks to the following: Kathryn McKee, Sub-Librarian and Special Collections Librarian, St John's College; Huw Jones, Head of Cambridge University Digital Library; Dr Orietta Da Rold, Associate Professor, Faculty of English and St John’s College; Abigail Farrow and Fergus Holmes-Stanley, Department of Anglo-Saxon, Norse and Celtic, and St John’s College; Prof. Pádraig P. Ó Néill, Department of English, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; Dr Elizabeth Duncan, Devon; Nicolle McNaughton, Hills Road Sixth Form College, Cambridge.

We are grateful for the assistance of St John’s College Communications Office, and to other College staff for facilitating filming; to the Cambridge University Digital Library for digitisation and hosting of the digital images of the Southampton Psalter; and to St John’s College for a grant from the Annual Fund to develop this resource.

Video Credits

Music provided by the choir of St John’s College Cambridge, directed by Andrew Nethsingha; organist James Anderson-Besant

Image of vellum production provided by:

William Cowley Parchment Makers

Manuscripts featured:

St John’s College, Cambridge

MS C.9 (The Southampton Psalter)

MS N.31 Mortuary roll of Amphelisa, Prioress of Lillechurch

MS D.30 Psalter of Simon de Montacute

MS A.8 Josephus

MS L.1 Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseide

Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

Macclesfield Psalter

Portraits:

Henry Wriothesley (after Michael Jansz. van Miereveld)

Thomas Wriothesley (engraved by Thomas Wright after the original by Peter Lely)

Documents:

Crawshaw’s signature reproduced from SJCA/D105/189

MS U.3 Shelf-list of St John’s College Library, Cambridge, with a record of later donations and purchases. 1634-90.

Printed books:

John Speed The theatre of the empire of Great Britain…, 1614. Bb.8.14

Crashaw monogram from Calvin’s commentary on Isaiah, 1583. Pp.3.8

Items from St John’s College Library and Archives are reproduced by permission of the Master and Fellows of St John's College, Cambridge.